International Heritage Centre blog

A Year in the Life of Florence Booth

A Year in the Life of Florence Booth

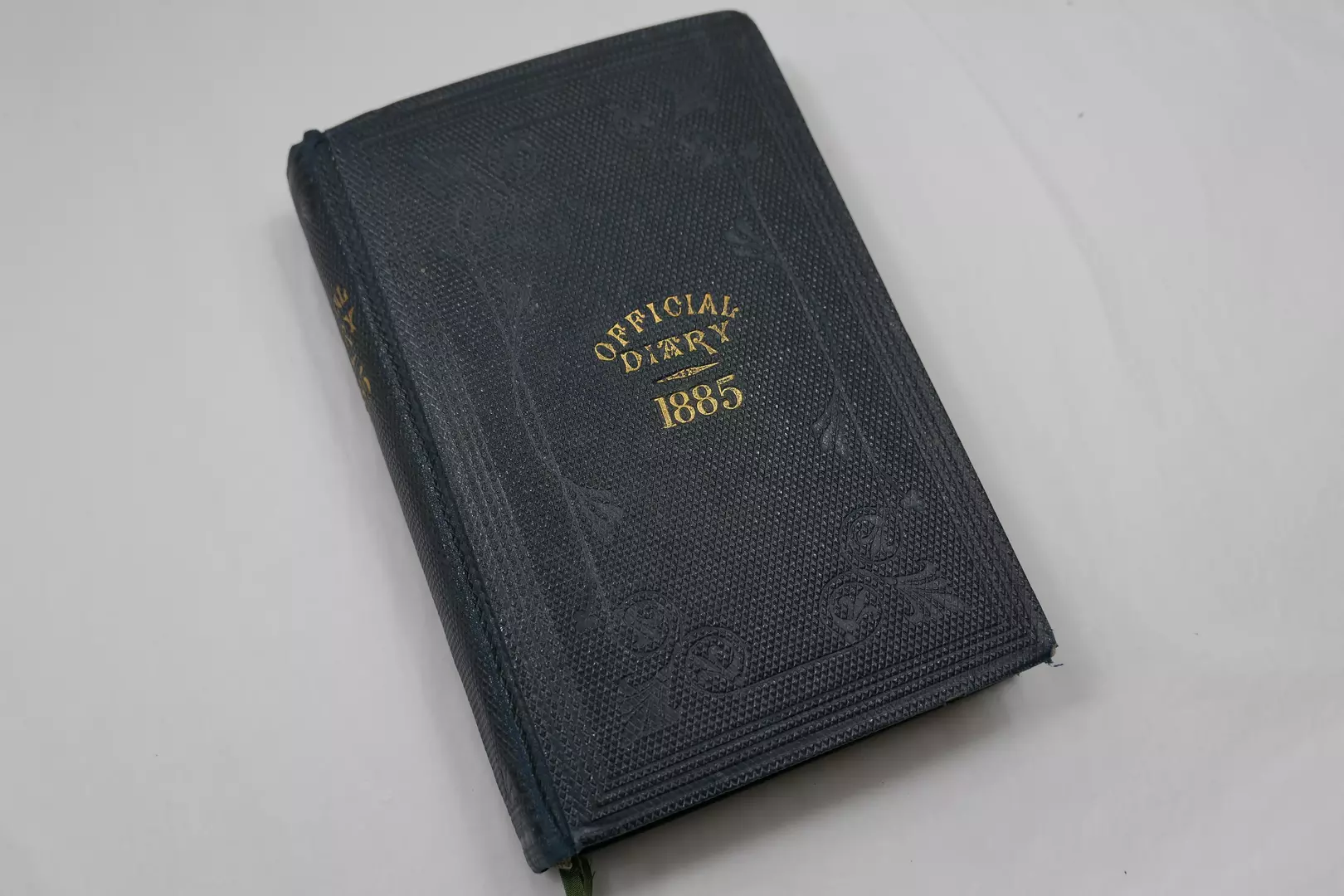

Condition checking our display collections during the Covid-19 pandemic has given me an opportunity to take a closer look at some of the precious artefacts that reside in our permanent exhibitions space. From the origins of the Christian Mission, to uniform, musical instruments and overseas mission, our onsite museum in Camberwell provides a wide-reaching perspective on The Salvation Army’s history and heritage; but ever since my first step into the museum, it’s the Social Work section that’s been my favourite. With relics from Hadleigh Farm Colony, the ‘Darkest England’ initiative, and Strawberry Field children’s home, this exhibit space tells stories from charitable campaigns that The Salvation Army has been carrying out since the early 1880s; and it’s within the Rescue Work cabinet that I discovered an item of particular intrigue: a diary kept by the Head of The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Work department in 1885.

The diary’s author was Florence Booth [née Soper] who had joined The Salvation Army aged 19 in 1880. By 1884 she had been promoted to Head of The Salvation Army’s Rescue Work and Women’s Social Work (WSW) which she successfully led until 1912. Upon discovering that this diary had yet to be explored in detail, I couldn’t resist delving into it. I soon found that this small and unassuming volume provides a poignantly personal snapshot into Florence’s life and work within The Salvation Army, in the suburbs of London where we join her with the new year, on 1 January 1885.

In the style of a new year’s resolution, Florence pledges her first penned words of 1885 as:

These words immediately signpost Florence’s steadfast character with a dedicated drive for self-improvement alongside a heart-warming optimism and compassionate outlook on the world. We know from several archival sources that both Florence and Bramwell Booth practised vegetarianism for at least part of their lives in complementation of their views on economy, health, and animal welfare, as discussed in our ‘Eat like a Christian’ blog post. Moreover, faith, hope and love are stalwart values of Salvationist belief and practice, dating back to the origins of the movement in the 1860s. Florence embodied these values, and as the diary develops we witness her active discipleship, waking early to carve out individual ‘time with the Lord’ before breakfast, and drawing on her faith for strength in times of leadership such as speaking at public prayer meetings (2 Jan).

Although Florence’s determination and capability shine through in her account of daily duties which primarily consist of managing the WSW accounts, finding domestic service positions for refuge girls, maintaining an extensive correspondence, supporting and visiting rescue homes, documenting refuge work and the women’s experiences (not to mention caring for a toddler and a baby!); this diary also reveals its role as a secure space where Florence expresses her innermost emotions, including her fears of failure and at times feeling ‘downhearted’ and ‘depressed’ (29 & 31 Jan). Despite demonstrating an outward appearance of confidence and success, in this private channel of thought she exhibits a tendency toward self-consciousness and lack of confidence, particularly to inspire and lead others – ‘Oh! How I wish I were a talker that could inspire people’ (18 April). This insight into Florence’s evaluation of herself demonstrates the irreplaceable value of personal papers as an historical resource; shedding light on the lived experiences of individuals, providing exclusive perspectives on historic narratives, and adding depth to outward appearances.

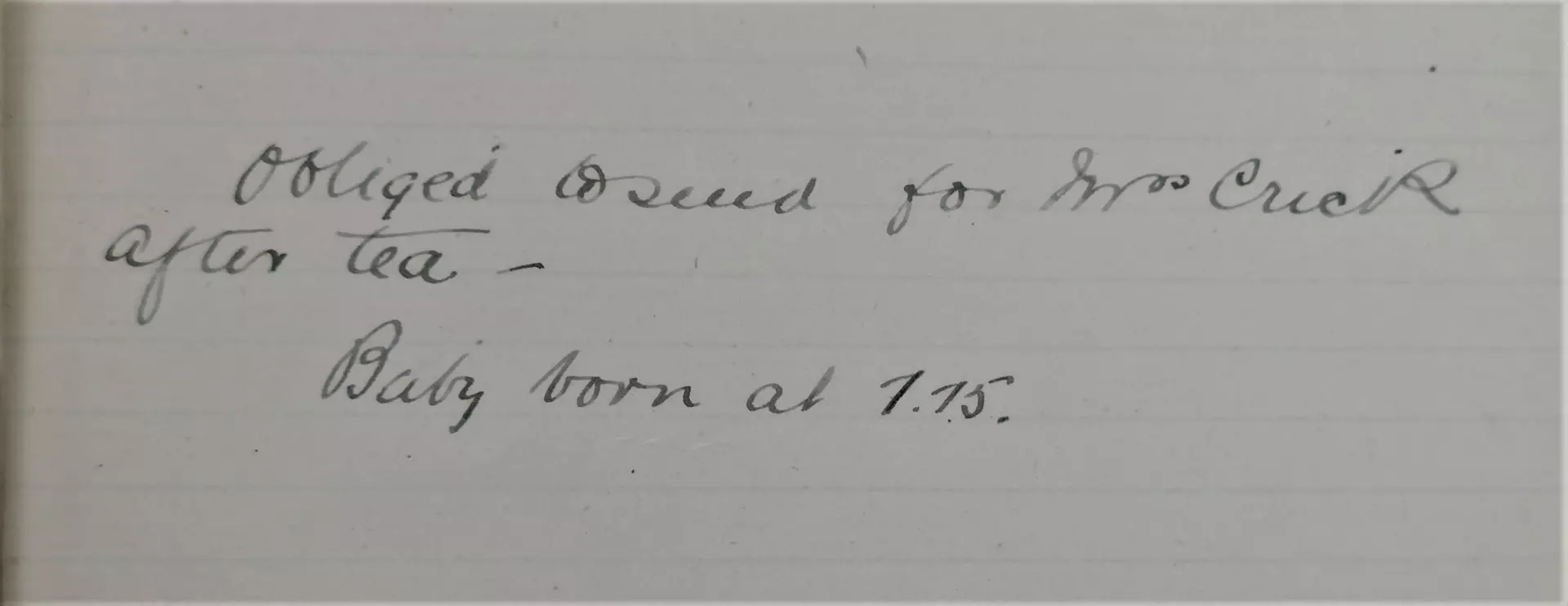

In contrast with her emotional candour, at times I was struck by extraordinary lapses in information that led to a sprinkling of surprises throughout the text. The most prominent perhaps being the first indication of pregnancy on her day of delivery:

Such conflicts emphasize the acutely personal and subjective essence of diaries, intended for the author’s eyes and their personal comfort rather than an in-depth and instructive historical record for later readers. Whilst in some contexts this would be seen as a fallibility of the diary as an historical source, identifying the information that Florence chose to include or exclude contributes to our understanding of her character.

Illness and death shadow the diary throughout, striking a close chord in the light of two years of pandemic. As well as the death of Florence’s own mother just a week before Florence gave birth to her second daughter Mary, through the diary we experience the emotional burden of the deteriorating health of her mother-in-law, Catherine Booth. From dysentery and seizures to ‘an attack of her heart’, concern for Catherine’s wellbeing peppers the diary, illustrating a pervading fear of illness and the fatality that frequently attended it in Victorian Britain. Moreover, this theme strikes in the first few pages of the diary as Florence agonises over the poor health of both her firstborn Catherine and her husband Bramwell who for most of the winter are ‘very poorly’, suffering periodically with cold, cough and fever. Catherine would in fact live on to the impressive age of 104 which seems an unlikely achievement given the heart rendering descriptions of her health during infancy.

On 11 February Florence writes ‘B still very poorly. Took his breakfast in bed – first time since we have been married’. Florence repeats this tender tone to Bramwell whom she had married on 12 October 1882, referring to him as ‘my precious love’ and ‘my darling one’, declaring in November that

Another developing relationship that features frequently in the diary is that with Rebecca Jarrett. Florence introduces us to Rebecca in January when, after a period of illness Jarrett undergoes a crisis of faith, teetering on the precipice of her former life as a brothel mistress. Florence’s restoration of Rebecca’s faith with an intense evening of prayer and reflection proves a pivotal move as Jarrett goes on to play an integral role in one of the most infamous events in Salvation Army history just four months later. In June 1885 Jarrett agrees to participate in the staged purchase of a child, Eliza Armstrong, for W T Stead’s press exposé on London’s child sex trafficking scene.

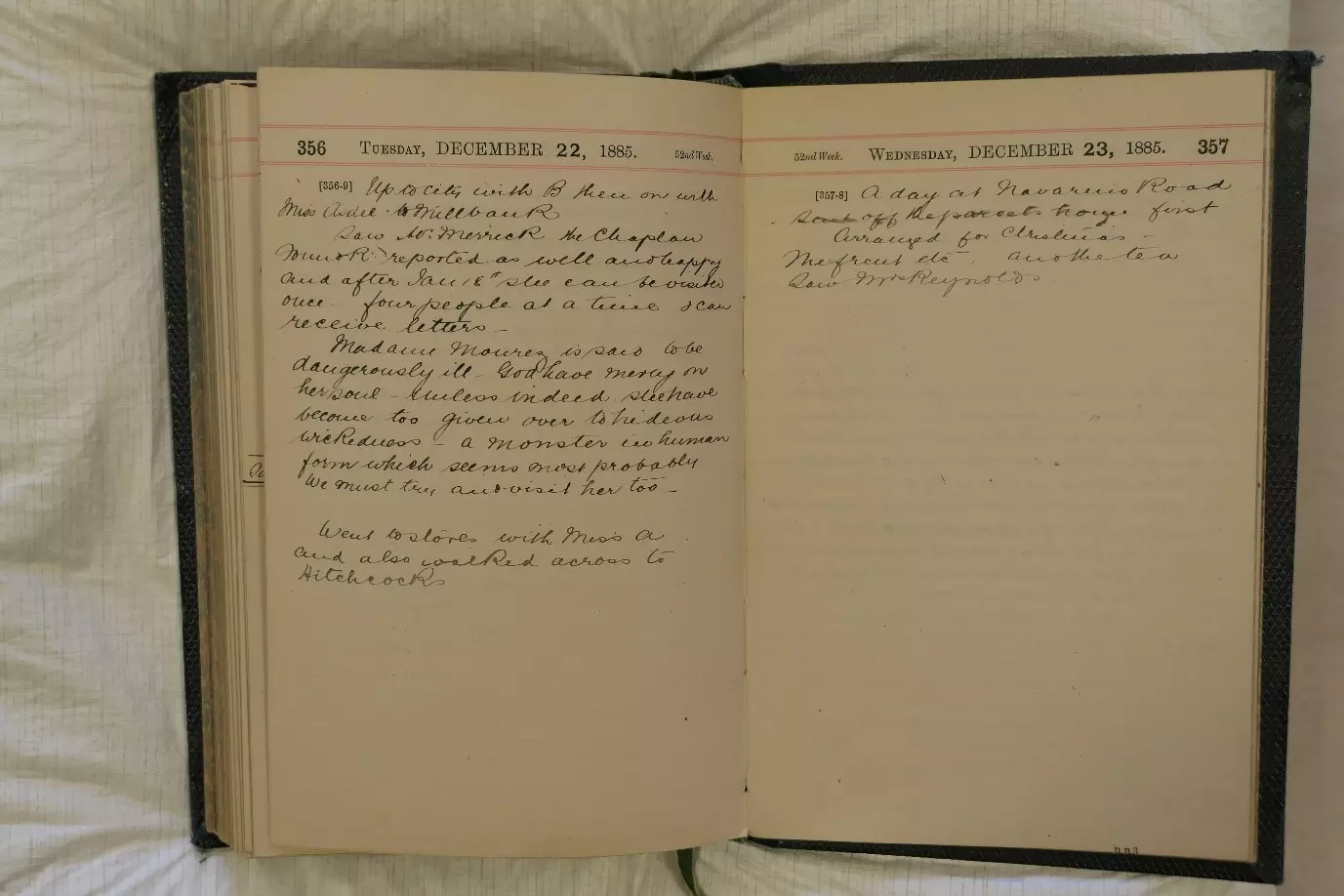

Stead’s ‘Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’ articles that recounted these events led to his arrest along with Rebecca Jarrett and Bramwell Booth who had been complicit in the staging. Through Florence’s diary we receive a blow-by-blow account of the proceedings from ‘Eliza Armstrong seen by Rebecca at Mrs Broughtons’ (2 June), to ‘Eliza Armstrong bought’ (3 June), ‘Detectives coming to see B’ (30 August), ‘R before the magistrate…summons against Bramwell’ (2 Sep), and ‘the Last day of the Old Bailey’ on 10 November. Florence describes the court proceedings from the perspective of one whose life would be changed immeasurably should her husband be convicted. Whilst many Salvation Army officers were no stranger to imprisonment due to persecution in the early days of its establishment (see our blog post on the Skeleton Army), Bramwell was destined to become The Salvation Army’s second worldwide leader and as well as supporting a wife and two young children, was already a prominent figure within The Salvation Army’s London Headquarters. To Florence’s relief, Bramwell was acquitted but Rebecca went on to serve a six-month sentence throughout which she was visited by Florence, cementing their lifelong friendship.

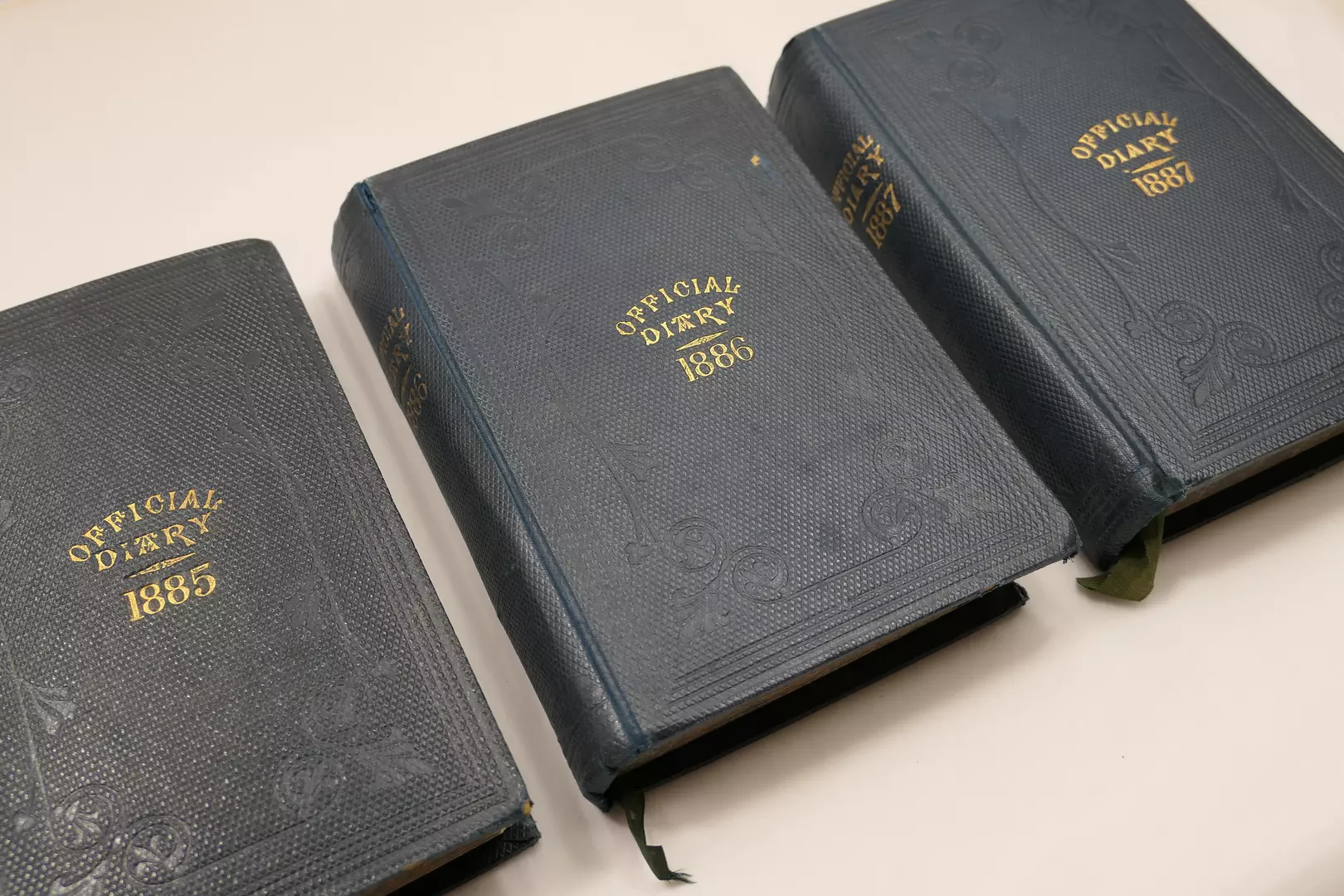

The Salvation Army’s social work programmes and the Maiden Tribute trial hold longstanding attention and interest from both academics and the public. Indeed, in March this year we look forward to sending W T Stead’s prison uniform to The British Library where it will feature in their Breaking The News exhibition. In light of this interest, it seemed an opportune moment put my palaeography skills fully to the test and transcribe the diary to make it more widely accessible. We’re thrilled that the transcript has already proved a beneficial resource for several researchers, and we are now hoping to transcribe Florence’s other diaries in our collection (two further complete diaries from 1886 and 1887 as well as loose extracts from later years). In order to achieve this, we’ve launched an exciting volunteer project so that others can help us to continue this journey with Florence from 1885 through to 1912.

Florence’s 1885 diary has taken us through a tumultuous year in which she was in her second year leading The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Work department; settling into marriage and motherhood with her first child as well as being pregnant and delivering her second; and weathering the storm of her husband’s arrest and trial for his involvement in the Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon exposé... I can’t help wondering what discoveries lie in store for us in the remaining diaries!

Chloe

January 2022

For more information about our permanent exhibition head to our Virtual Heritage Centre and for more information about Rebecca Jarrett and her involvement with the Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon case see my blog post ‘Unmade in Modern Babylon’ for the East End Women’s Museum.

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

Guest blog: Honor Salthouse, 'The Oldest Soldier in the World'

Winette Field, Librarian of William Booth College, returns for another guest blog relaying the findings of a collaborative research project into the life of The Salvation Army's 'oldest soldier', Honor Salthouse.

Collections Care at The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre during COVID-19

Read about what The Salvation Army Heritage Centre team has been up to behind the scenes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

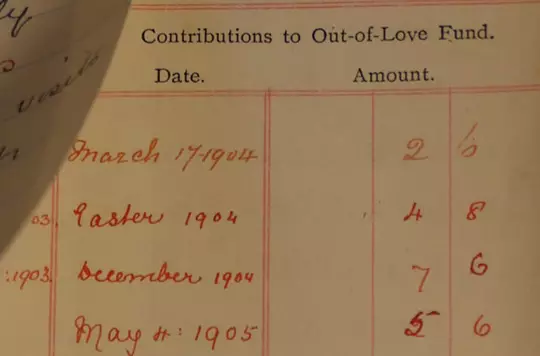

Out of love and small earnings

Find out more about the Out-of-Love Fund, money that 'out of small earnings was gladly and spontaneously given’...

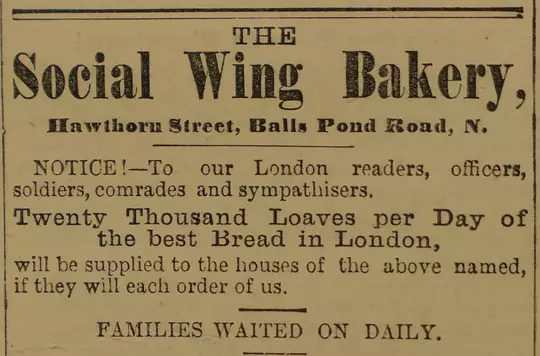

Pastries with Principles: The Salvation Army's Social Wing Bakery

Read all about The Social Wing Bakery, one of The Salvation Army's late nineteenth century social schemes!