International Heritage Centre blog

Dedicated Followers: Uniforms and the Nineteenth-Century Salvation Army’s Attitudes to Fashion

Dedicated Followers: Uniforms and the Nineteenth-Century Salvation Army’s Attitudes to Fashion

Everybody recognises a Salvation Army uniform. But what was behind their introduction in the late nineteenth century?

The Salvation Army uniform remains one of the organisation’s most visible and distinctive attributes. The uniform was formally adopted in 1878, but while the suggestion met with enthusiasm from many officers, in practice most uniforms were makeshift at first, and did not become standardised until around 1880. The process of phasing in the uniform, especially for soldiers, then took several years. Salvationists bought their own uniforms, which was also financial proof of their commitment to the organisation, as in 1890 a uniform cost about three weeks’ wages. You can see a video showing the evolution of Salvation Army uniforms from the 1880s to the 1990s in our Virtual Heritage Centre. This blog post explores some of the reasons behind the uniform’s introduction and particularly its links to wider contemporary debates about fashion.

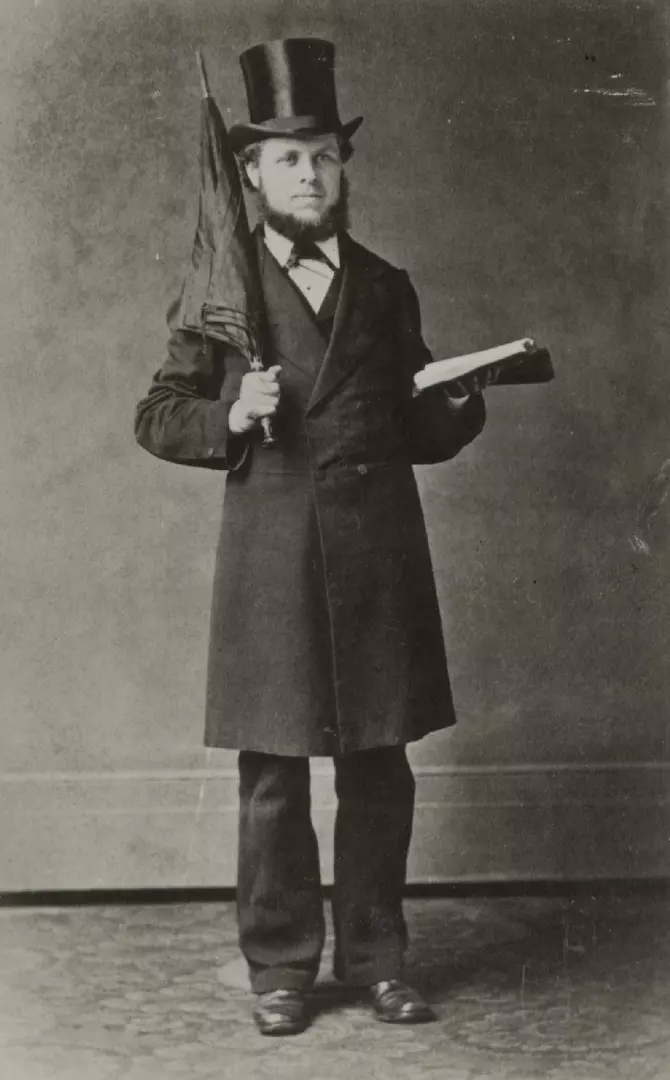

In volume II of The History of the Salvation Army (1950), Colonel Robert Sandall noted that a dress code had already existed in The Christian Mission, William and Catherine Booth’s original mission in east London and The Salvation Army’s predecessor. For women, this meant ‘plain dresses’ and ‘small Quaker-type bonnets’ and for men, ‘suits of clerical cut, with frock coats, tall hats, black ties’.

The reasons for these unassuming outfits were linked both to religious convictions that rejected worldly vanity and to practical applications. For example, umbrellas were carried ‘for leading singing during processions’. Meanwhile,

In times of riot a tall hat was a good mark for missiles, but at others it had special advantages – it was not unusual for an evangelist who wanted to gather an audience in the open air to place his hat on the ground before him and address it until a crowd had been attracted!

The iconic ‘Hallelujah bonnet’ worn by women Salvationists from the 1880s into the 1990s had its roots in the same ‘times of riot’, when adherents would be regularly attacked by groups like the Skeleton Army during open-air meetings and processions. Catherine Booth sought to establish the wearing of a form of headgear that was ‘cheap, strong and large enough to protect the heads of the wearers from cold as well as from brickbats and other missiles’.

The visibility of the uniform was also an act of defiance against the violent opposition the early Salvation Army faced from across the social and political spectrum. In 1883 William Booth stated that ‘when so many would fain stop our public processions, how important for every soldier to be so dressed as to make a public demonstration every time he crosses his threshold’.

As well as signalling individual Salvationists’ commitment and advertising the organisation, however, uniforms did additional cultural and religious work for The Salvation Army. In 1886, when the uniform was still relatively new, the Orders and Regulations for Field Officers emphasised the importance of uniform-wearing particularly for newly converted soldiers. They argued that:

Uniform will be found to deliver its wearer from much temptation. The Soldier feels he cannot trifle with sin in any shape when in uniform without bringing discredit on The Army and dishonour to God, and many people seeing his uniform, will not approach him with any suggestions to do evil, expecting that as a Salvationist he will naturally reject them.

In addition to helping Salvationists avoid temptation, however, it was also ‘a magnificent exercise in self-denial for the wearer’. This meant the giving up of ‘all worldly finery, such as gold and silver ornaments, flowers, feathers, fashionably-cut apparel, and the like’. An interest in the secular topic of fashion was not deemed compatible with a spiritual commitment to The Salvation Army’s religious teachings. An added argument, also raised on this blog in relation to abstaining from animal products, was doubtless financial: not spending money on smart clothes left more to donate to The Salvation Army. Sandall points out that Catherine Booth wanted the bonnet to be ‘neat and distinct from mere worldly fashion’: poke bonnet-style headgear had gone out of fashion earlier in the century.

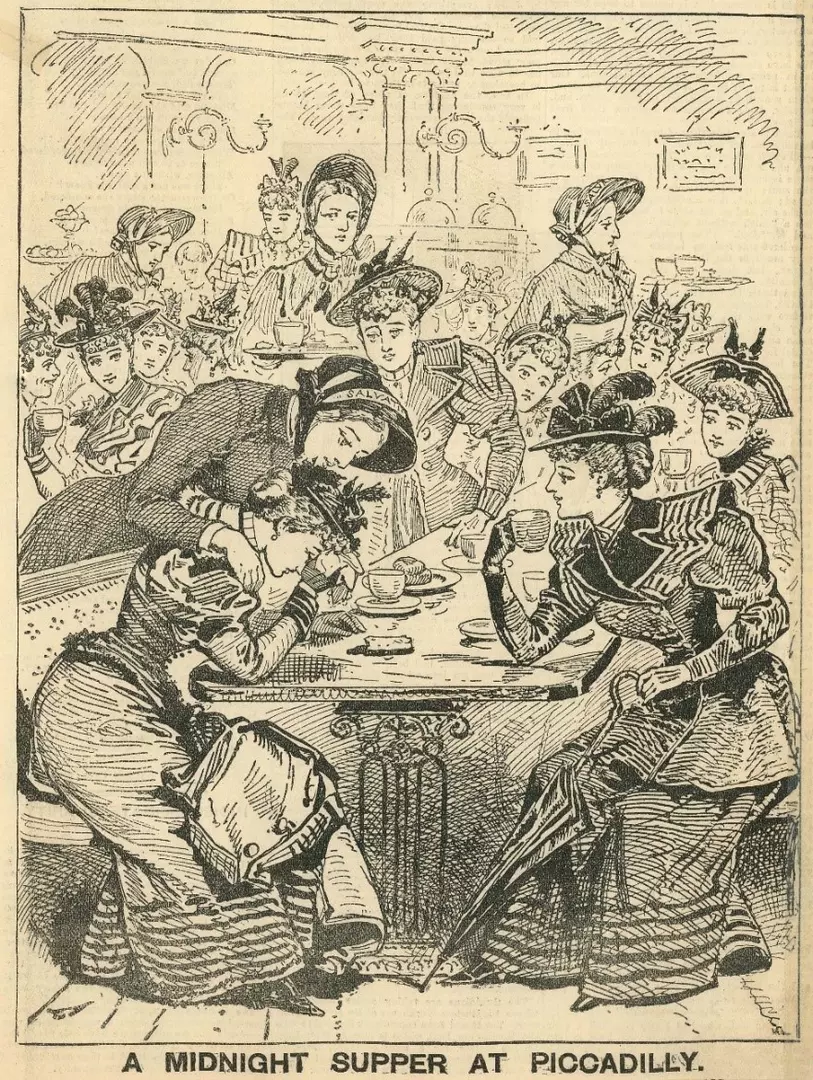

These attitudes also speak to wider contemporary concerns about fashion. At a time when a growing number of people had a disposable income while the price of clothes was dropping, fashion became an interest within the reach of larger social groups. In response, social commentators began to raise their concerns about women’s dress, particularly in relation to young working-class women who, they felt, failed to dress modestly. One well-known example of a popular magazine article on this topic is ‘The Girl of the Period’ (1868) by Eliza Lynn Linton. In such commentaries, bright colours, clothes that were tight-fitting or low-cut, and decorative features such as feathers and flowers were often associated with women in sex work. There was a significant undercurrent of social control to these debates, as it was argued that women who dressed in this way laid themselves open to harassment. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Salvation Army uniform was seen as protection from unwanted attention, particularly for young women working in deprived areas and potentially hostile environments such as pubs. In contemporary images of the Rescue Work, the contrast between the outfits of women Salvationists and the women that sought their help is often emphasised, as in the image of a ‘Midnight Supper’ for sex workers in the Piccadilly area of London.

In many ways the uniform is symbolic of the establishment and wide cultural acceptance of The Salvation Army. In its function of signalling the wearer’s dedication and advertising the organisation it went from defying opposition to achieving recognition and even affording protection. Understanding of the uniform and its role have evolved over time with conceptions of fashion and appearance.

Flore

July 2021

In Greenest India

Archivist Ruth Macdonald takes a look at a tree-planting initiative undertaken by The Salvation Army in India in the early twentieth century.

All the World’s a Fair: The World-Wide Salvation Army Exhibition, 1896

125 years later, we revisit the 1896 exhibition in the context of the nineteenth-century history of World Fairs.

Davie Haddow, the converted international footballer

As the 2020 European Championship nears the finals, our Director, Steven Spencer, reflects on the life of Davie Haddow, The Salvation Army's 'Converted Footballer'.

The accession in the suitcase

For archivists, the arrival of an unexpected parcel tends to raise mixed emotions...