International Heritage Centre blog

‘the creatures He made’: Animal Welfare in Salvation Army History

‘the creatures He made’: Animal Welfare in Salvation Army History

This blog post is adapted from the conference paper ‘“the creatures He made”: Animal Welfare in Salvation Army Literature, c. 1890–1930’, presented by our Digital Humanities Project Officer Flore at Animal History Online: Borders and Boundaries, the annual conference of the Animal History Group held digitally on 19 June 2020.

References to the importance attached to animal welfare in the early history of The Salvation Army regularly crop up on this blog. Treating animals with kindness and humanity is often presented as an important aspect of a Christian life. Our Director Steven has written about how members of the Band of Love, the Salvation Army-run children’s temperance organisation, promised to ‘try to love all and be kind to Animals’. There were economic considerations to Salvationists’ attitudes to animals and animal products as well, however. Our Archives Assistant Chloe quotes an officer’s advice on caring for working horses in the waste paper works of the Men’s Social Work, which is strongly linked to the fact that horses were a valuable resource. In both Chloe’s post on Katie Booth’s old coat and my own on vegetarianism, there is a sense that the use of animal products, including fur and meat, was discouraged for Salvationists because these products were expensive, and saving on them left more funds to donate back to The Army. Nevertheless, Salvation Army institutions such as Hadleigh Farm did produce animal products for the market. The early Salvation Army’s attitude to animals seems to be closely related to Genesis 1:28, in which humans were given stewardship over other animals – but any use made of animals should be respectful and free from abuse or mistreatment.

The wellbeing of animals and people was clearly seen as interconnected. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century people and working animals relied on each other, and the best results would be achieved if both could have a long and healthy working life. This idea informs initiatives such as the so-called Cab Horse Charter that General William Booth invoked in his 1890 blueprint of The Salvation Army’s social work, In Darkest England and the Way Out. The welfare of London cab horses had become a popular cause following the publication of Black Beauty, Anna Sewell’s 1877 novel exploring the lives of working horses. Booth referred to the benchmark for care given to cab horses – ‘When he is down he is helped up, and while he lives he has food, shelter and work’ – to argue that people should be entitled to the same.

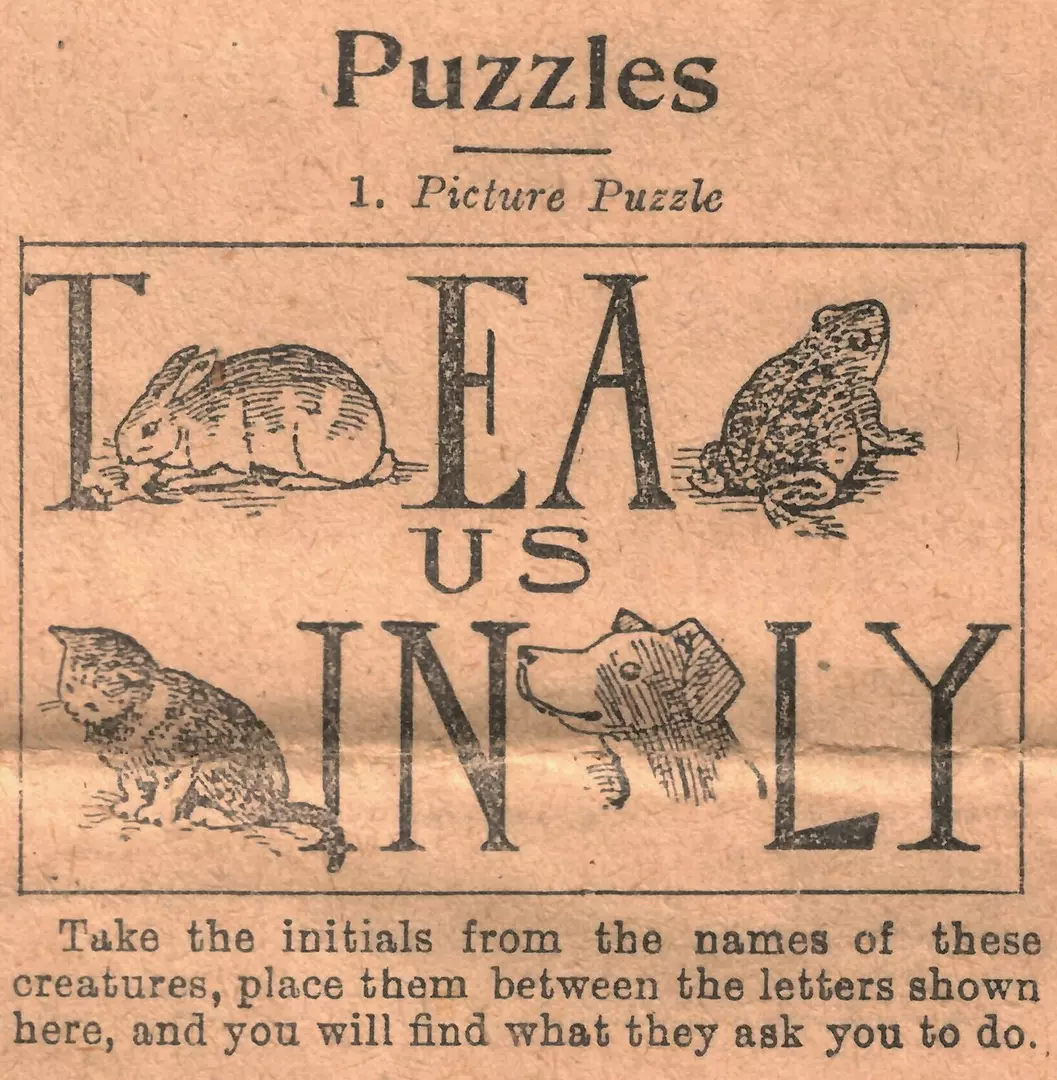

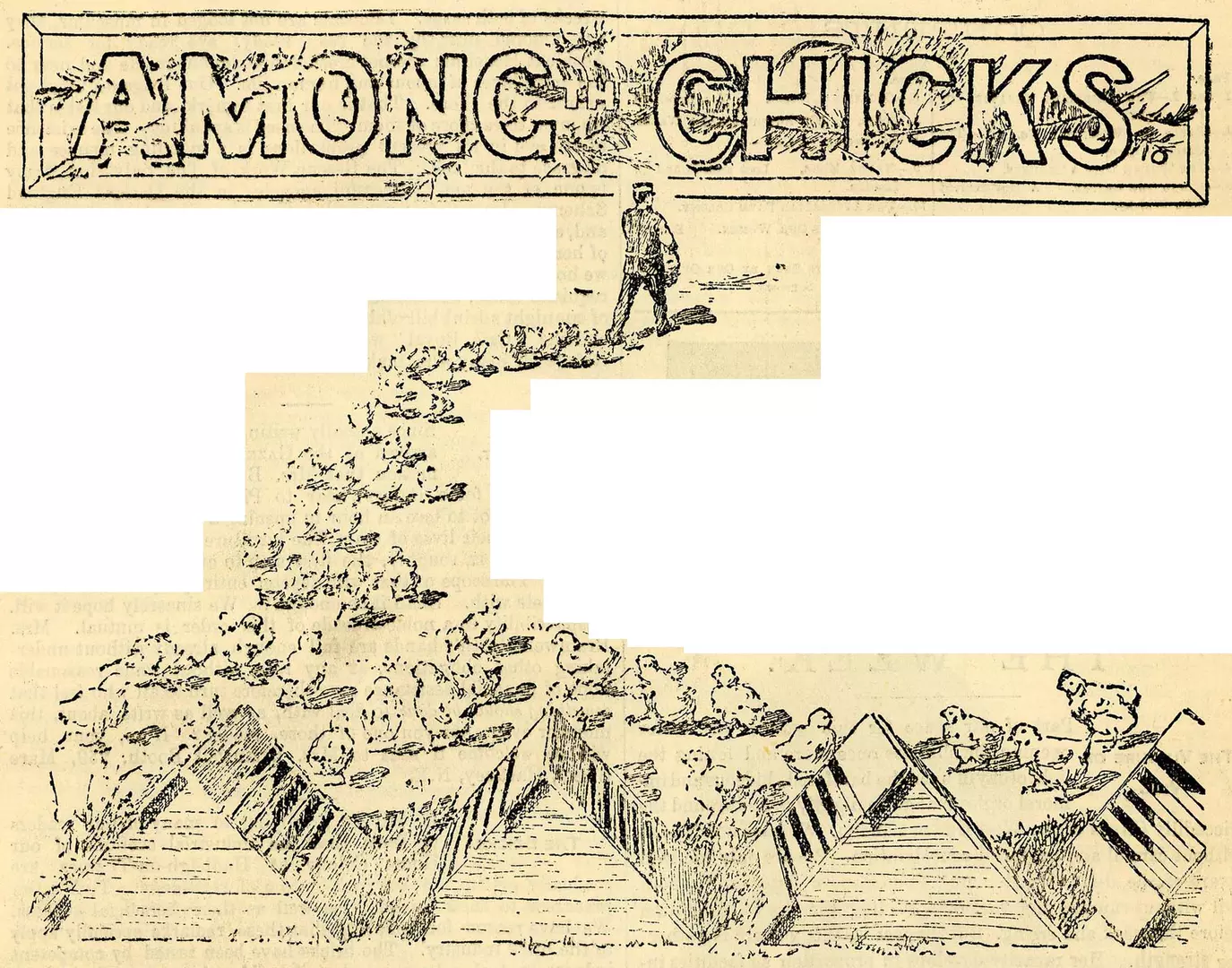

While The Salvation Army remained focused on people, animal welfare is a recurring theme in The Darkest England Gazette, the weekly magazine dedicated to the Social Work between 1893 and 1894. In the early issues references to animal welfare and animal suffering frequently appear in the short fragments of news and remarks that filled up leftover column space. These might, for instance, pick up on reports in other publications of blood sports or mistreatment of working animals and present these as examples of condemnable cruelty. In later issues reports also start to appear on the importance of animals in The Salvation Army’s agrarian ventures.

One key contemporary animal rights cause that found its way into The Darkest England Gazette is the high-profile issue of vivisection. Surgical experimentation on living animals was widespread in medical research and training during the period, and activists from many different backgrounds campaigned for it to be banned. The Booth family were opposed to vivisection and corresponded with anti-vivisection campaigners. Between 7 April and 9 June 1894, The Darkest England Gazette included a series of contributions from Edith Carrington (1853–1929), a prominent anti-vivisectionist who seems to have had no other connection with The Salvation Army. Her contributions are clearly geared towards The Salvation Army’s Christian ethics, however, and Christian responsibility is central to her arguments.

According to Carrington, caring for animals is a Christian duty signifying mercy and humility. Her contributions follow three key tenets: the un-Christian attitude of vivisectors, practising Christians’ resilience in the face of suffering and death, and the dangers of breaking down moral barriers to cruelty. Evoking Genesis, she argues:

[Animals] were delivered into our hands for food, clothing, and help; but never in order that their beautiful forms, the work of God’s fingers, within and without, should be mangled, burnt, scalded, bruised, torn to pieces, to satisfy the curiosity of a barbarous surgeon as to how the marvellous thing was made.

In other words, all animals are God’s creation, which humans are not entitled to violate. It follows that those who practise or defend vivisection act in an un-Christian way. Carrington states:

The vivisector’s religion may rightly be described as Materialism, or a kind of worship of the body, because he seeks to obtain for himself or others a long life, and freedom from pain, no matter at what risk to the soul. […] Now, those who have a spiritual religion know that pain is not altogether a real evil, to be shirked at any price. […] If we seek to get rid of pain, or even death, by means of a sinful action, we murder the soul, and lay up eternal misery for that!

Elsewhere, she also argues that Christians derive from their faith the strength to endure suffering, so that they ‘have no need to seek to shuffle pain off upon beings less able to bear it than themselves’.

Rather than ultimately improving people’s lives, then, this kind of experimentation in fact causes both individuals and society to deteriorate morally by devaluing the very concept of care. Carrington asks: ‘Can young men, who begin life by trampling on every merciful instinct, be fit for the profession of healers in after years?’ As these doctors’ moral instincts were worn away, she suggests, they would become less respectful of other life, and even become tempted to treat human bodies as further experimental material, rather than seeking to heal them. In an article entitled ‘Human Vivisection’ she states: ‘From the helpless dog to the defenceless baby is one step, the next leads to the almost equally feeble invalid mother…’ This argument asks for animals to be taken into account in The Salvation Army’s understanding that no human life is worth less than any other. If it is clearly no more acceptable to experiment on an infant than on its exhausted mother, Carrington asks, why should it be permissible to practise the same cruelty on a dog or any other species?

In the early Salvation Army, caring for animal welfare was considered part and parcel of a Christian’s duties. Although the use of animal labour and products was not prohibited, it was felt to be important for a number of reasons to make use of animals in ethical ways. Failure to do so was associated not only with social and economic irresponsibility – as by hurting valuable working horses, for instance – but also, as Carrington shows, posed a direct danger to one’s own spiritual welfare. By hurting animals, people were likely to end up hurting themselves as well as others in the long run.

For more information on Animal Welfare in The Darkest England Gazette, please see our research guide.

Flore

April 2021

Davie Haddow, the converted international footballer

As the 2020 European Championship nears the finals, our Director, Steven Spencer, reflects on the life of Davie Haddow, The Salvation Army's 'Converted Footballer'.

The accession in the suitcase

For archivists, the arrival of an unexpected parcel tends to raise mixed emotions...

Women's History Month 2021 roundup

This blog post brings together the resources that we have shared via social media, throughout Women's History Month 2021.

Getting Under the Covers in Book Conservation

This month Archive Assistant, Chloe, relates her experience at CityLit's interventive archival conservation course.