International Heritage Centre Blog

Death in the Archives

Death in the Archives

The Internship

For my Spring term, I had the good fortune of being selected by Birkbeck to act as an intern at the Salvation Army Heritage Centre, spending eleven weeks with the Women’s Social Work Statement Books to see what I could learn about the women contained within.

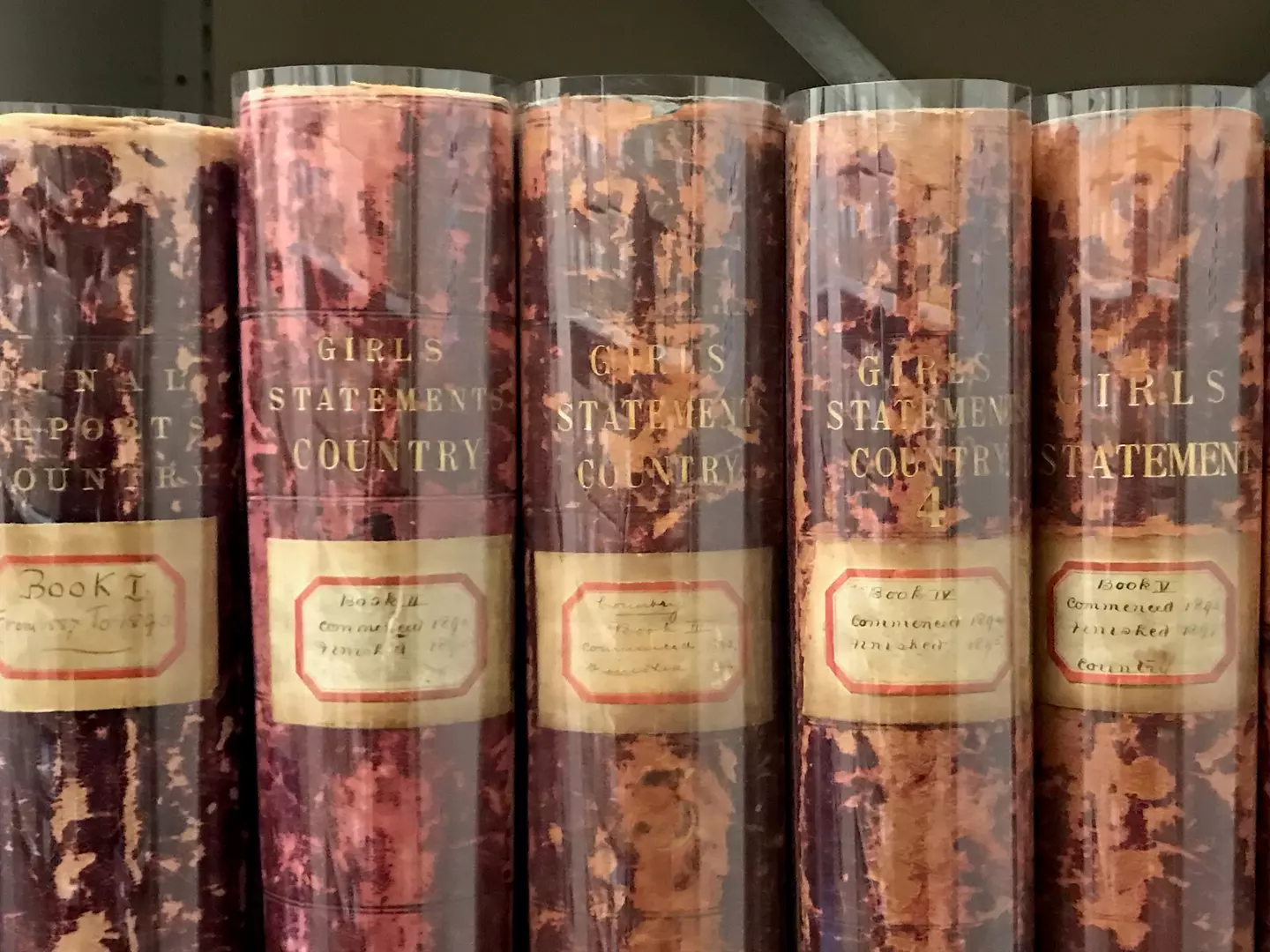

Unsure of what to expect, I pulled up outside William Booth College to see what might wait inside. On the third floor of a wonderful twenties building, tucked away in what was previously officer’s quarters, sits the Salvation Army Museum, alongside archival storerooms and a reading room with one of the best views in London. After being shown around the storerooms and museum, and learning about different approaches that can be taken in an archive setting, I settled down with the Statement Books I was going to become very familiar with over the next eleven weeks.

The Sources

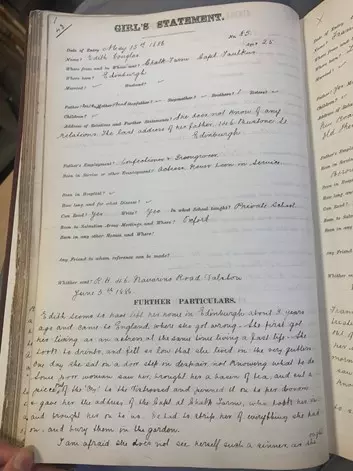

The primary sources I investigated were the first two Girls Statement books for the Salvation Army’s London-based social work. These books, with their first entries dating from 1884 and 1886, detail a single-page record for each woman that was accepted into the London rescue homes. The entries, as you can see above in figure 1, provide biographical details like the woman’s age, name, and place of birth, details on family members, literacy information, and a narrative section titled Further Particulars near the bottom which is a mixture of what the women reported, the interpretation of that narrative by the person filling in the record, observations made by the Army of the women, and the outcome of further investigations.

As historians, we have to acknowledge the various biases and limitations that exist in records like this, and understanding these was my first task. Ascertaining the veracity of the information is a key limitation. A number of the records explicitly state that, in the opinion of the officer filling in the form, the recorded information was inaccurate, with the woman suspected of lying. While other biographical information can occasionally be found to shed light on some of the claims such as date of birth, where a bias is explicitly stated, it is hard to know how faithfully the information provided by the women was recorded. Even without explicit recognition of a bias, it can be impossible to know if some of the information provided was accurate or if the women’s stories were entirely, or in part, fabricated perhaps featuring minor or wholesale embellishments in order to present a story they felt may enhance their chances of receiving help.

There is also a limit to the extent that wider cultural assumptions can be made from the limited number of the records surveyed, I was only able to read through 172 of the thousands of records available in the Statement Books. The records do not represent an accurate cross-section of the entirety of society, or even of the working classes from which the majority of the women are drawn, and do not detail every type of hardship that could be faced.

Finally, the specific entries are often open to interpretation. While many of the entries give a specific account of the location of their parents, the records often display a simple slash in the entry for Father or Mother - were they dead, absent, or just unrecorded, it can be impossible to know. Despite these limitations, however, the recorded entries preserve fragments of individual lives that otherwise would be lost to history. My exploration of them represents the recovery of those fragments and an attempt to try and understand the specific trends that touched these lives.

The Dashboard

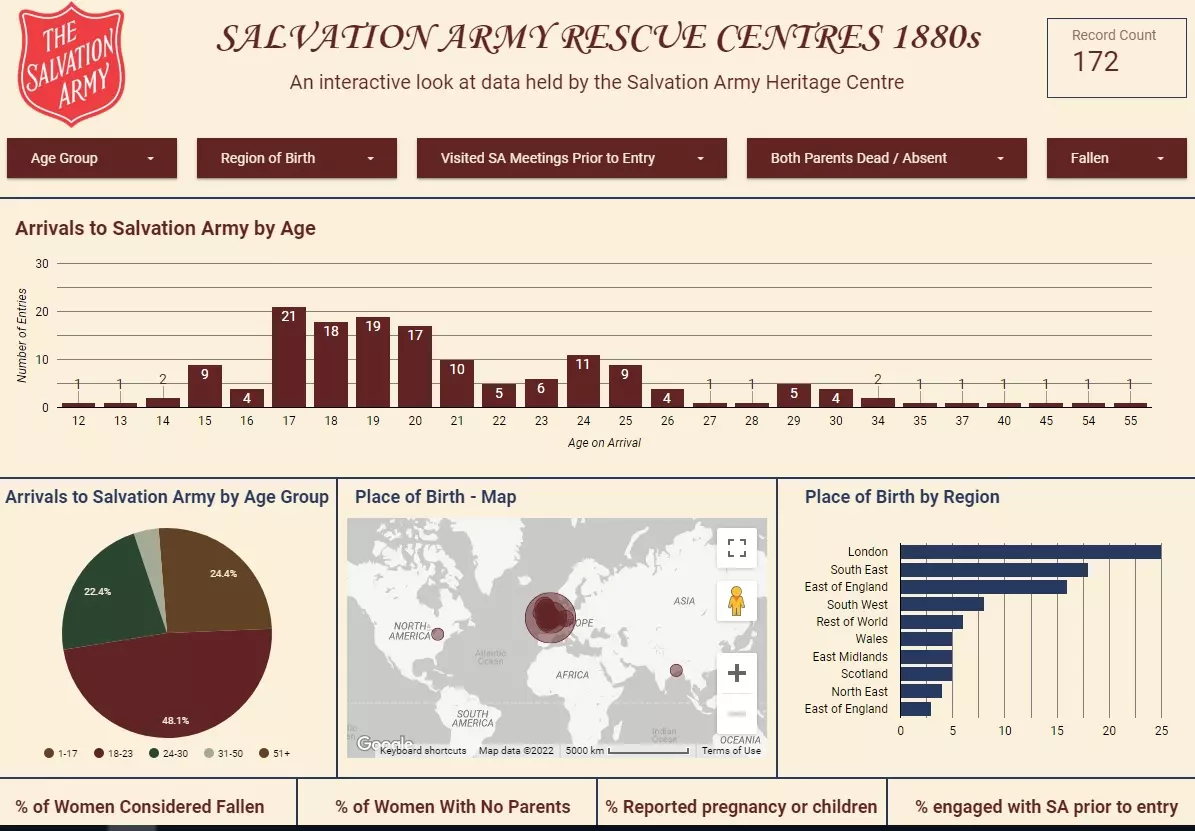

As part of the internship, I agreed to create a spreadsheet detailing all of the entries I read. This would create a digital archive of the nineteenth-century records that could be more easily searched by internal staff to try and understand the available content in a new way. However, after a couple of weeks of populating the table, I realised that there might be something better I could create. Something that might let the public interrogate the data in a more interactive way, bringing the data to life. To do this I created a dashboard, below.

Some of the data you will see is a direct reflection of the information held in the records, such as age, place of birth, and literacy information. Others, required me to make judgements and collate information from different parts of the records, applying my own definitions. For example, there was no specific field relating to whether or not a woman was to be considered ‘fallen’. In order to create this field, I chose to define a fallen woman as one that had had sex outside the confines of marriage, whether consensually or not, and whether or not it was in exchange for money or goods - this in itself often required judgements to be made on the information provided. For many of these women, this was easy to ascertain, for others I had to extrapolate based on the information found in the narrative section of the records.

This high-level, distanced approach to reading the records enables you to get an understanding of the trends in the data, that may otherwise go unnoticed if you were to rely solely on a close reading approach of individual records. By using the five custom-built filters found across the top of the dashboard you can change the data underneath it to build up a picture of the women from the 172 records, depending on your specific interest. For example, by filtering to the 1-17 age bucket you can see that 50% of the 38 women in this cohort are considered fallen, but this percentage rises to 82.86% when considering the 24-30 year old cohort. Alternatively, you can use the region of birth filter to discover that 84% of the women born in London reported being able to read and write, but for all those born outside of the capital these figures drop to a reported 81.4% being able to read, and 78.4% being able to write. Or, of those who had previously engaged with the Salvation Army prior to arriving at the Rescue Home 25.83% of them reported at least one previous pregnancy or child, compared to only 18.52% of those that had not.

Death in the Archives

Having spent some time analysing the data, it became clear that a large number of the women reported at least one significant death or loss prior to arriving at the Army’s Rescue Home. The dashboard shows that around a quarter of the women reported having no parents, and around 60% reported any death or absence of a parent.

When approaching death in the nineteenth-century, historians are able to draw on abstracted figures that detail national or regional level death rates, using data drawn from census records and death certificates which show how and where people died and at what age. Alternatively, they can draw on material culture or realist literature that, in part, gave its contemporary audience a way to understand and use the high mortality rates for their betterment. For example, Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton shows that through repeated exposure to death the titular character was able to mature, learning how to mourn and through this develops an empathy that ultimately allows her to have a happy ending within the novel. By relying on either the fictionalisation of death or its statistical abstractions it is easy to overlook the real people that were fundamentally impacted by the high mortality rates.

There were other types of loss recorded, of course, beyond death. There was willful abandonment by various parents who simply left, and for fifteen year old Jane Wood (SS/2/1/1 No. 34) her mother had entered an asylum nine years previous leaving the seven children of the family to ‘run the streets’ as her father struggled to cope. For the women and girls left behind these types of loss could be every bit as final as those linked to death, but it is clear in the reading that the death of one or both parents, or other caregiver, child, or partner contributed to many of the women seeking help from the Army.

Women like Ellen Winter (SS/2/1/1 No. 30), who at 24 was received into the Salvation Army’s home on 16th March 1886. Ellen had been ‘engaged to a young man, who in an hour of temptation seduced her and evidently intended marrying her very shortly, but when she was three months pregnant he was thrown from a horse and killed.’ Following his death, Ellen moved jobs, forced to leave her home in Hackney where she did not want ‘anyone to know of her condition’. The removal of her soon-to-be husband, combined with the physical proof of that relationship in the form of her unborn baby, meant that Ellen felt a level of shame that would not have existed had her fiancé survived. This death meant she left her role, and ultimately entered Islington Workhouse. After discharging herself from the workhouse, on 16th March 1886, she sought the Salvation Army’s help the same day.

Alice Edith Barrett’s story (HSNR/1 No. 27) again shows us the impact of the removal of a family support network. Both of Alice’s parents had died, and after moving from Torquay to London, Alice ‘kept company with a man’ who eventually took her to meet his aunt. Unfortunately, the record details that the two of them tricked her into living in a brothel where ‘it was rumoured that the Prince of Wales and Lord Randolph Churchill also frequented’. Though she ‘became the special property of a young Doctor’, after ‘a month or more’ she was able to escape and found her way to her brother’s house where her sister-in-law ‘nursed her till the brother came home, who turned her out of doors’. This removal of support led to her walking the streets until she was brought to the Salvation Army, and by July 1885 she was recorded as ‘doing well in a situation in Croydon’.

Conclusion

My time within the archives allowed me the chance to learn something of the lives of women that I otherwise would never have heard of. By engaging with these nineteenth-century documents, and by applying twenty-first century methods of data visualisation I was able to pull out the high-level themes that link these women beyond their presence in the records. I chose to look at death and loss as the astonishing prevalence and intrusion of it into these women’s lives was clear. However, while I have chosen to focus on death, the dashboard may show other links between these women that open up new ways of understanding these lives and I hope that by interrogating the data yourself, you may be able to find stories that grab your interest.

Link to the dashboard: https://datastudio.google.com/u/0/reporting/36639fc2-698f-42b3-adeb-647b32229b60/page/zAakC

Lucy

October 2022

‘Evangelical Thrust’: The Salvation Army in the New Towns

In the 20th century the landscape of Britain's towns and cities began to change and the architecture of Salvation Army halls changed with them.

‘A New Kind of Help’: Comforts in the First World War

Find out about The Salvation Army's role in making and distributing comforts to British servicemen.

A garden lover's gem

This month’s blog ties in with #GreenWeek which takes place between 24 September and 2 October, raising awareness of issues associated with climate change and celebrating community action to protect the environment.

God Save The Queen!

Inspired by the platinum jubilee we bring you a potted history of Queen Elizabeth II’s relationship with The Salvation Army through the lens of our archives.