International Heritage Centre blog

Soup, Soap, and Salvation: The Armée du Salut in the penal colony of French Guiana in the 1930s and 1940s

Soup, Soap, and Salvation: The Armée du Salut in the penal colony of French Guiana in the 1930s and 1940s

[L'Armée du Salut is the French name for The Salvation Army]

Our fourth guest blog is written by Clare Anderson. Clare is Professor of History at the School of History, Politics & International Relations, University of Leicester. She has previously undertaken research on the activities of The Salvation Army in the Andaman Islands of British India, which is open access (free to view) here. Her current work on the Armée du Salut in French Guiana arose during a larger project on the global history of penal colonies. Both interests underpinned the development of a research collaboration between the University of Leicester and the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre. With the Heritage Centre’s Director, Clare is supervising an ESRC Midlands Graduate School funded PhD student, Adam Millar, whose focus is the Army’s overseas migration schemes, from 1890 to 1939.

Among the materials held in the archives of French Guiana in the outskirts of Cayenne is a box of papers relating to the activities in the colony in the 1930s. These add considerable texture to related archives in the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre. French Guiana became a penal colony in 1854. It held under-sentence convicts from all over France and its empire, and ex-convicts who had served their term (libérés). This was because under the French law of doublage, convicts sentenced to more than 7 years were not allowed home until they had stayed in the colony for an equivalent number of years. With the labour market already saturated by convicts, many of them fell into destitution.

In 1929, following the scandal that broke in Europe after journalist Albert Londre returned to France and reported on the inhumanity of conditions in the penal colony, the Armée du Salut received permission from the Ministry of the Colonies to despatch Adjutant Charles Péan to investigate. He did so, returning in July 1933 with the first contingent of Army officers. Their aim was to establish an infrastructure of support for the libérés. By this time the French Ministry of the Colonies had set up its own commission of enquiry, and it directed the Army to work closely with both the governor, Julien Lamy, and the director of the prison administration, Colonel Prével, in relief operations.

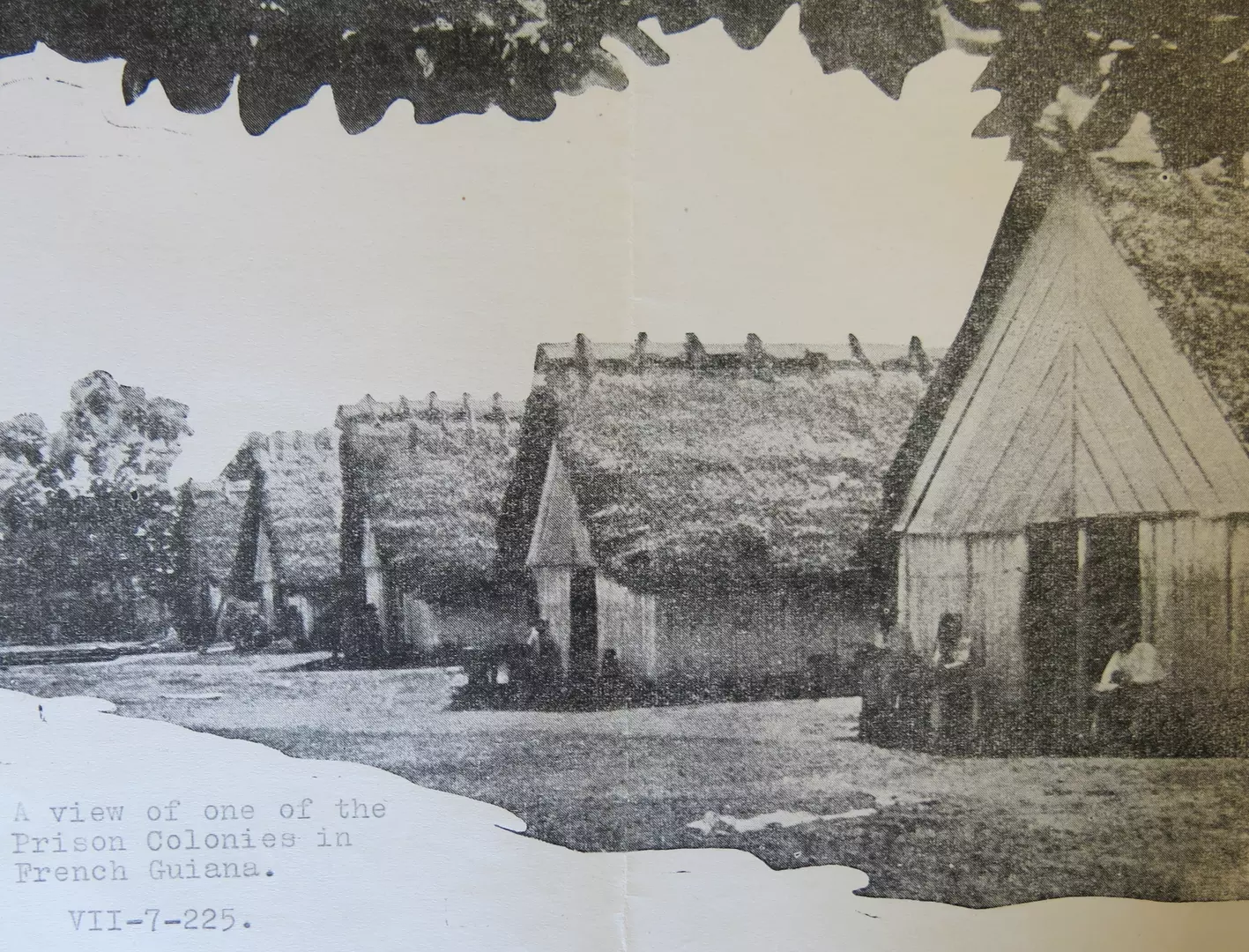

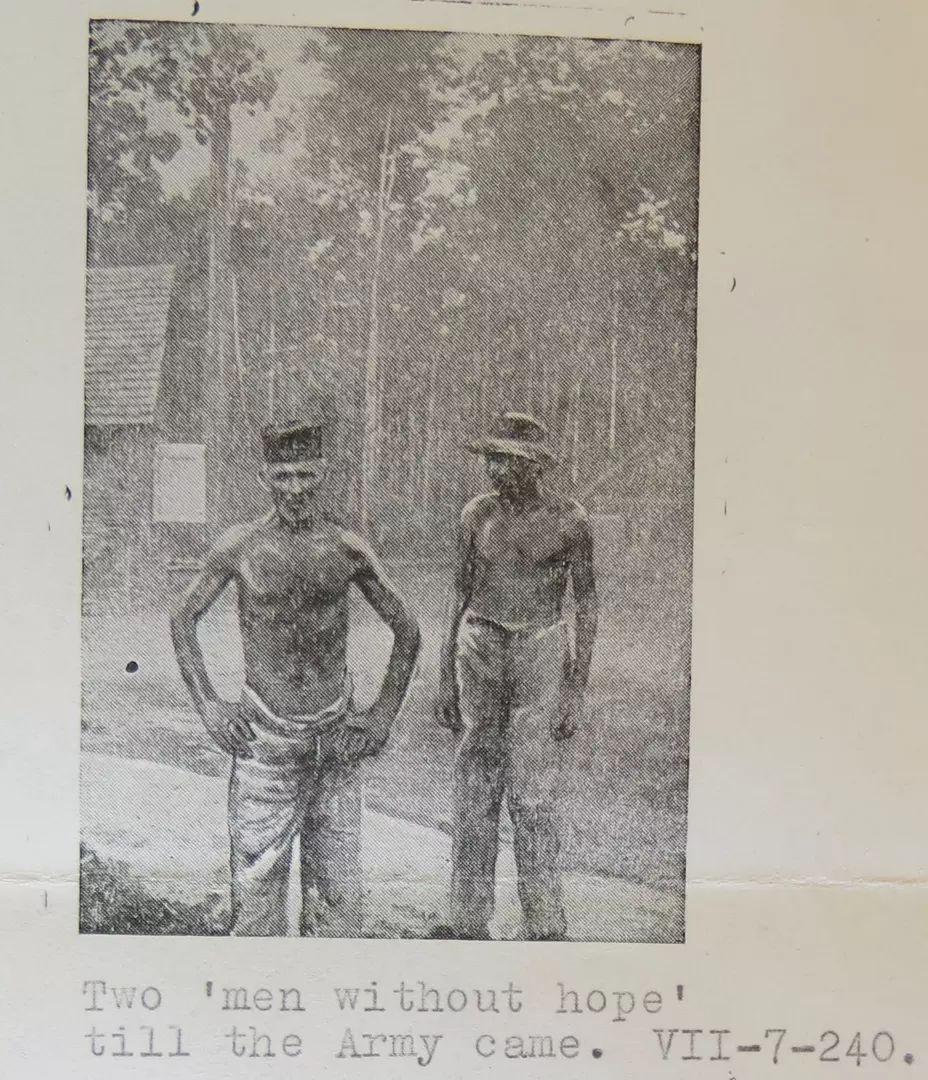

At this time, there were just over 3,000 convicts in the colony, men who had been condemned to hard labour for life. They lived either in the capital at Cayenne, or in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni on the river border with Dutch Surinam. There were also around 2,000 recidivists, men who were sent to the colony for repeat offices. They lived in the same area, in the Camp de la Rélégation (Recidivists’ Camp) in St Jean. A handful of political prisoners lived offshore, on the notorious Devil’s Island. Finally, there existed an unknown number of libérés (at least 1,500), the released prisoners who were compelled to stay. It was mainly with the latter group, most of whom were unemployed, with which the Army became concerned.

Building on earlier work among the homeless, by prison chaplain Father Adolphe Naegel who established a free dining hall (La Soupe Populaire) in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni in the 1920s, the Army was allocated an unused building, which it inaugurated as a foyer. It included dormitories, a meeting and recreation room, and a restaurant. This largely replaced the pre-existing Asile de Nuit (night shelter), though unlike previously libérés were obliged to pay a small charge. Meantime, the Army established a headquarters in Cayenne, and a workshop for the manufacture of souvenirs. It had plans also to set up businesses for fruit canning and charcoal production, though ultimately the workshop was used to manufacture furniture for local use, and the Army also sold butterflies and insects to overseas collectors.

A few kilometres outside Cayenne, under the charge of Lieutenant Klopfenstein, the Army also established a colonie agricole (agricultural colony, or farm) which it called Montjoly. The original intention was to grow vegetables that could be supplied to the Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni restaurant, but it developed to include also a chicken farm, piggery, and banana plantation – with fruit from the latter exported to France. Back in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, two Army officers joined the Committee of Patronage, to assist the libérés, one of them as vice-president. They enjoyed considerable power, keeping a portion of the libérés’ wages until they left the colony (in the belief the men were not responsible enough to do so themselves), and even being allowed to keep the savings of men who died.

The power of the Army in the colony was such that in 1935 the Commissioner of Police in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni complained that the population of the town regarded it as nothing less than a commercial operation. The Mayor agreed. ‘[I]t is,’ he wrote, ‘rather curious to find that the representative of an organisation that passes for philanthropic … systematically refuses to let a poor man sleep in its night shelter if he does not have 0.50 francs to pay.’ Colonel Prével, director of the prison administration, added that he had received numerous complaints against the organization. For example, libéré restaurant owners complained that the Army’s foyer had put them out of business. Libéré workers alleged that the director of operations in Saint-Laurent, Captain Chastaginer (or, Chastagné), had failed to deposit their wages in the bank on their behalf, as he was supposed to do; kept money that he was supposed to send to relatives overseas; and not shared funds or tickets sent from France for their repatriation.

Traders in the town were not altogether happy about the presence of the Army either: some claimed that Chastaginer owed them money, and others that he had sold clothes sent from France that were meant for charitable distribution. The police officer in charge of the libérés, Gendarme Lavaud, added that the Army told workers at Montjoly that it would pay for their repatriation after two years of service, docking wages in the meantime to cover the fare. However, not only did this contravene the law of doublage, the Army deliberately got rid of workers before this time was up, claiming that they were poor workers, had misbehaved, refused to convert, or were bad Christians. It then kept their accumulated wages. If anybody did convert, Lavaud added, they were made to write a letter to France, which was seen as a means of soliciting donations.

Though he noted that disputes were always resolved amicably, director of the prison administration Prével added further concerns. He claimed that Chastaginer sold garden produce from the foyer garden clandestinely at the market; and on several occasions had tried to access convict records, which were beyond his authority. Prével surmised: ‘the Salvation Army here is neither a charitable nor a humanitarian organisation. It is a commercial firm that looks to profit by all means, [and] shows no pity to the libérés.’ The Army itself had a somewhat different perspective. Pioneer Salvationist Charles Péan viewed operations in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni as ‘flourishing’, explaining away any difficulties by noting ‘[o]ur operation in French Guiana is hampered by continual difficulties inherent in the category of men that we look to help.’

Governor Lamy attempted to intervene in these disputes, suggesting that the Army was profiting from the foyer, and withholding the pay of libéré workers dismissed from Montjoly. He also suggested that they encourage men to come to the foyer by allowing the serving of alcohol. Unsurprisingly for a member of a temperance organization, Charles Péan firmly rebutted this, responding that alcohol had caused ‘indescribable misery, ruin and eternal damnation,’ and that only total abstinence could guard against its dangers. He added that the Army made a loss from visitors to the foyer and that it was good practice not to pay men who were dismissed from the farm due to poor conduct. Péan added: ‘Without speaking of moral benefit (the most important) if these men allow our principles to penetrate them and open their hearts to God they have good and plentiful food, leisure, and books.’

Commisioner Albin Peyron, who travelled out to the colony in 1933, further reported the gratitude of the men he had encountered. One, he claimed, told him: ‘Your words are a balm poured upon our suffering.’ Another: ‘I thought I was alone in my sorry, but I find hands stretched out to help me – I hear a voice crying, “Courage! All is not lost! It is a miracle, an unhoped-for miracle; it is help from Heaven. From now on I am going to live another life, a life of hope”.’

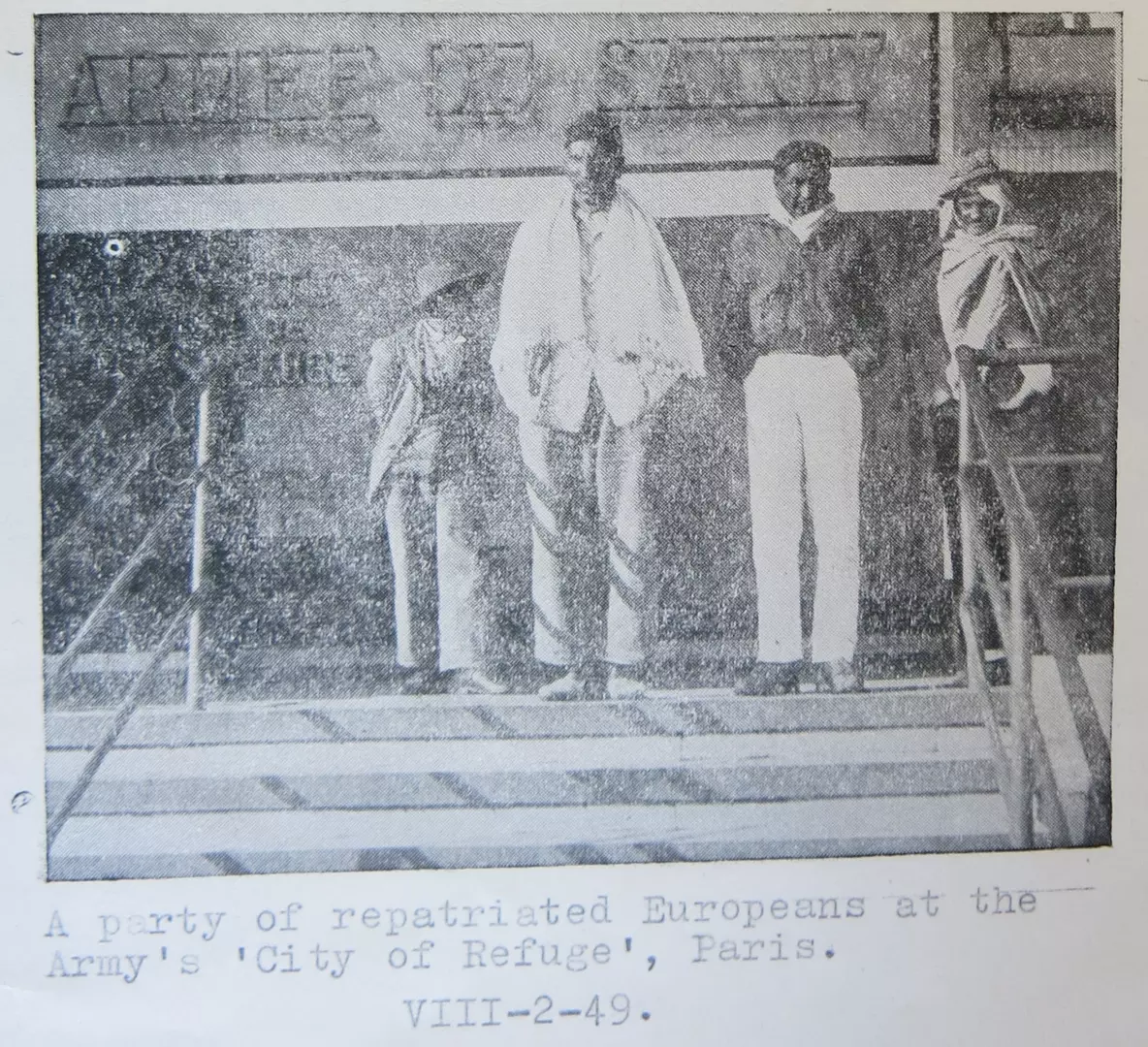

Back in Paris, the Army began to work with the families of the convicts and libérés, supporting efforts for their return home. This came in the wider context of French discussions about the closure of the penal colony, in which the Army was engaged. The first repatriations came in 1936, about half of whom went on to their homes in North Africa. The Second World War interrupted discussions about abolition, though the Army remained present in the colony. They greatly assisted the final repatriations, which took place during 1946 and 1947, including to Cassablanca, Algiers, and Oran. A handful of these former convicts ended up in the Army’s centre de relèvement et d’assistance par le travailat at Château de Radepont in Northern France, where they received assistance in the form of food and lodging.

September 2020

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

'Our Salvation Christmas Tree'

What made a Salvation Army Christmas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century?

The Great British (Archival) Bake Off

Discover some of The Salvation Army's archival recipes and our experiences reproducing them.

Tales from the Theatre

Archive Assistant, Chloe, reflects on the role that theatres and musical halls played in the formation of the Christian Mission.

Guest blog: Location, Location, Location

This month we have a guest blog from our Birkbeck University intern, Imogen, exploring the who, what and why of The Salvation Army's east end Knitting Home...