International Heritage Centre blog

‘Matches and Morals’: The Salvation Army and Consumer Activism in the 1890s

‘Matches and Morals’: The Salvation Army and Consumer Activism in the 1890s

SCENE: Grocer’s shop. Enter Salvation Army servant with her mistress’s child.

Servant: “Have you any Darkest England matches, please?”

Grocer (obligingly): “Not exactly. But my customers call these Salvation Army matches,” displaying some with red stems and yellow tips.

Servant (severely): “Is there any of the stuff in those that makes phossy jaw?”

Grocer (enthusiastically): “Not a bit, and they’re so cheap! Only twopence a dozen boxes.”

Child (pleadingly): “Oh, do get the dear little red and yellow matches!”

Servant: “Where were those matches made?”

Grocer: “Well—um—ah—somewhere abroad.”

Servant (righteously indignant): “And you'd ask me to buy matches ‘made in Germany,’ or somewhere, with poor people starving at home for work. No! If I’d never joined the Salvation Army I mightn’t have known any better; but, as it is, I know far to[o] much to buy matches made abroad.”

Exit Servant, explaining the horrors of foreign competition and necrosis to disappointed child.

- ‘Matches and Morals: A Dramatic Episode’, Darkest England Gazette, 10 February 1894.

This somewhat startling short dialogue uses the everyday example of a household shopping trip to illustrate the wide-ranging social impact of the production of matches in the late nineteenth century. It appeared in the Darkest England Gazette, a weekly periodical dedicated to The Salvation Army’s social work programme, the ‘Darkest England Scheme’. Both the scheme and the periodical took their name from In Darkest England and the Way Out (1890), the book in which General William Booth addressed the various social problems The Salvation Army sought to combat, such as poverty, unemployment, homelessness, hunger, slum housing, and prostitution. The Salvation Army had engaged in social work prior to 1890: the 1880s had seen the establishment of various different Brigades to work with homeless people, ex-prisoners, alcoholics, and other vulnerable groups. The ‘Darkest England Scheme’ centralised these efforts, and the Gazette served to reflect the aims, reach, and progress of the large-scale scheme.

One problem connected to the poverty and underemployment the social scheme addressed was the ubiquity of ‘sweating’, a labour practice characterised by a high workload, long hours, and low pay. While sweating often referred to home-based work, it also took place in factories, specifically those that employed large numbers of young women. Sweating had become conspicuous as a social concern in the late nineteenth century, due in part to a number of high-profile labour disputes involving underpaid workers. The Matchwomen’s Strike of 1888 played an important part in this history. The young women employed at the Bryant and May Match Factory in Bow, East London, went on strike to protest against their appalling working conditions, and their cause was taken up by prominent labour activists including Annie Besant.

The publicity gained by the Bryant and May Matchwomen raised awareness not only of their long hours, low pay, precarious employment, and fines imposed by their employers, but also of a medical condition known as ‘phossy jaw’ to which matchmakers were subject. The match production process contaminated the workers’ hands and food with toxic yellow phosphorus which caused their jawbones to decay with potentially fatal results.

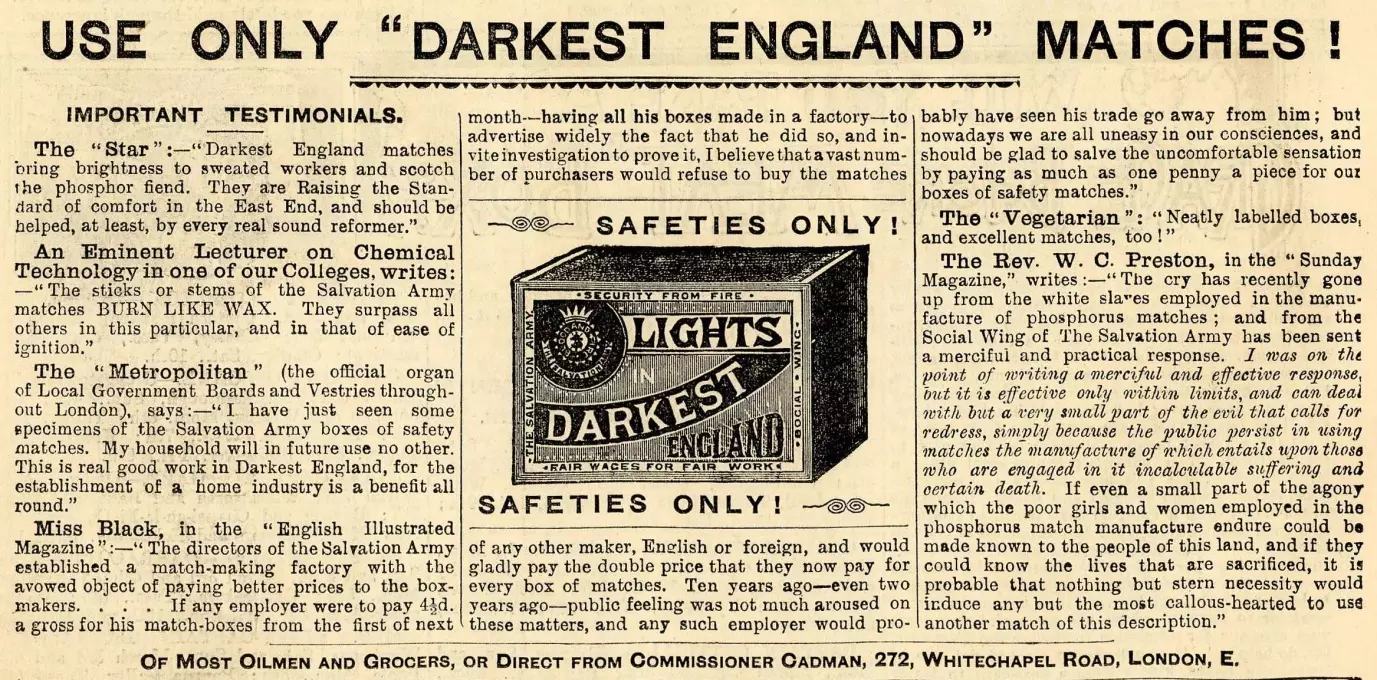

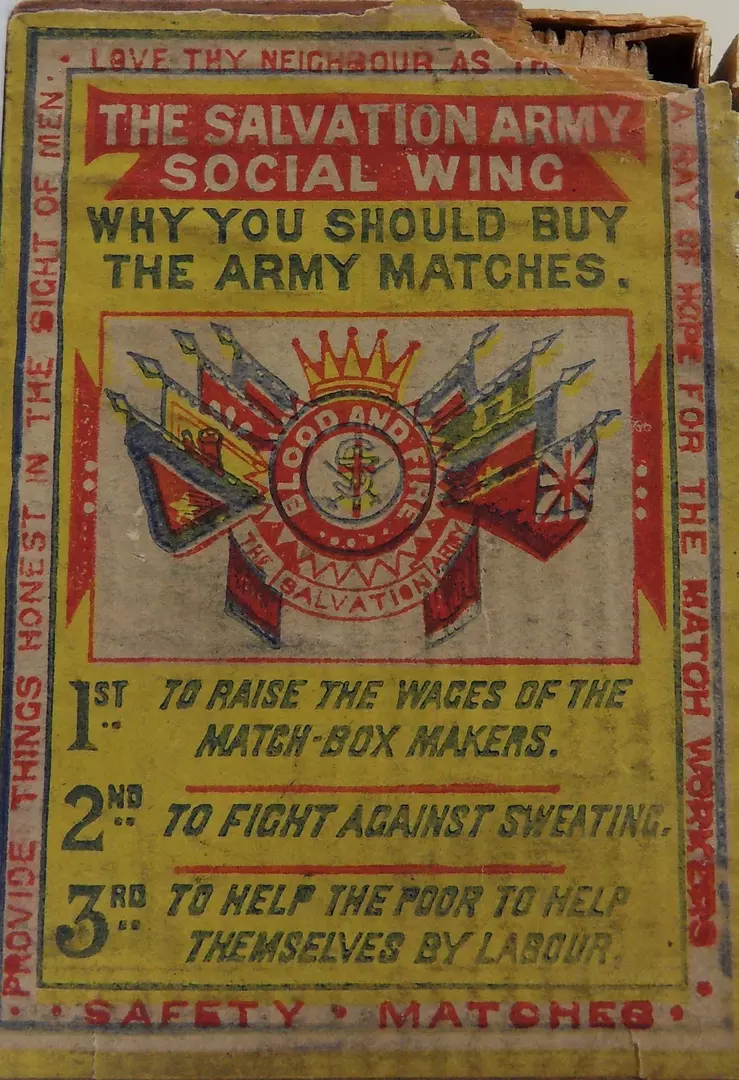

It is not surprising, therefore, that the plight of sweated matchmakers quickly became a central part of The Salvation Army’s social work. Historian Victor Bailey notes that the plans for a Salvation Army match factory ‘with the aim of undermining the large match firms’ originated with Frank Smith, a Salvationist with connections to the radical labour movement who was appointed director of the social work in 1890. The factory was opened in 1891 under Commissioner Elijah Cadman who had replaced Smith as director of the social work that year. The matches, produced under trade union-approved conditions without dangerous chemicals, were dubbed ‘Darkest England Matches’ and were widely promoted in the War Cry and, of course, the Darkest England Gazette.

The matches soon became the focus of a full Salvation Army consumer activist campaign. The Salvation Army press argued that no Salvationist, knowing about the horrors of sweating and of phossy jaw, should use any other kind of matches. The ban on other matches included those produced in other countries, such as Sweden or Germany, partly because their provenance could not be vouched for, and partly because foreign competition was argued to increase pressure on domestic workers. While the workers’ welfare was a prominent argument, the matches were also advertised as safer for the user than the ubiquitous ‘strike anywhere’ matches. Virtually every issue of the Darkest England Gazette included at least one advert for ‘Darkest England Matches’.

The match issue also pervaded other contributions to the periodical. Short fiction such as ‘Matches and Morals’, the ‘dramatic episode’ cited at the beginning of this post, were intended to lead by example: all Salvationists must approach their grocers in this way, putting pressure on shops to stock Darkest England Matches. The horrors of phossy jaw were put forward in stories like ‘Esther Daniels’ (published on 13 January 1894), an account of a death from the disease, or poems like ‘Phosphor Poison’ (27 January 1894). Lists of ‘Darkest England Match Agents’ showed which shops stocked the matches in different towns, and letters to the editor corroborated how easy it was to buy or order the matches. As a result, it was hoped, Salvationists and other readers of the Darkest England Gazette would have no excuse for failing to buy the approved kind.

What this persistent campaign concealed, however, was the fact that the matches were not, in fact, selling very well. Bailey notes that

The Army’s ‘safety matches’ were more expensive than the strike-anywhere type […] and sales began to plummet; even Salvationists were said to be buying the cheaper brands. The best consumers of the Army’s matches, according to the Officer, ‘are members of other denominations, Co-Operatives, and Trade Unions.’ Eventually, in December 1894, the match factory had to be temporarily closed.

It is likely that the Darkest England Gazette’s determined campaign to sell the Darkest England Matches early in 1894 was a result of awareness within the Social Wing that the match factory was suffering.

By the second half of 1894, the Darkest England Gazette had reinvented itself as the Social Gazette. The new publication makes no mention of the factory’s closure and its tone reflects a continued investment in the matchmaking scheme, albeit less confidently. An advertisement in the 29 December number announces that ‘In order to develop the sale of Darkest England Matches’, they will be stocked by The Salvation Army’s International Trade Headquarters in Clerkenwell, Central London. Meanwhile, it offers its readers the cheaper alternative of the ‘Briton Match’, giving the assurance in capital letters that ‘THIS [IS] NOT SWEATED!’

The Salvation Army’s scheme to take responsibility for the safe production and fair trade of matches proved inadequate to compete with the cheap mass production of an item indispensable to the nineteenth-century household. Nevertheless, the ambitious campaign for consumer activism, using the public-facing platforms of the Darkest England Gazette and the War Cry, was a forward-looking response to a widespread and high-profile contemporary social concern that remains familiar to us today.

Flore

July 2019

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

'Rescue and Deliver Them': Attending the British Association of Victorian Studies Conference

Our archivist provides an account of The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre's panel at the British Association of Victorian Studies 2019 Conference...

William Booth: The Man of Emotion

In our second guest blog, biographer Gordon Taylor shines a light on William Booth as a 'Man of Emotion'...

The ‘Old Coat’

Cataloguing our Booth-Clibborn collection of correspondence has taken me on an enlightening and entertaining journey...

A House Through Time: The Salvation Army at 5 Ravensworth Terrace

The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre was pleased to be involved in the research behind David Olusoga's BBC2 series, A House Through Time...