International Heritage Centre blog

'The New Exodus': The Salvation Army and Emigration

'The New Exodus': The Salvation Army and Emigration

One of our recent priorities at the IHC has been to establish how much material we have in our collections relating to The Salvation Army’s former Emigration Department and what this material can tell us about the Department’s work. It is a little-known fact that The Salvation Army was the United Kingdom’s largest voluntary migration society in the first half of the twentieth century, helping around 250 000 people to emigrate from the British Isles to the British Empire Dominions. Given the wide-reaching impact of this work and the considerable resources The Salvation Army dedicated to it, it is surprising how little evidence and knowledge of it there is now. This can be partly explained by the fact that The Salvation Army lost its International Headquarters along with many of the papers kept there in the Blitz. A recently discovered letter from Commissioner David Lamb, the director of Salvation Army emigration work for over 25 years, to George Carpenter, the wartime General of The Salvation Army, confirms what we had long thought—that many of Lamb’s personal and departmental papers were in International Headquarters when it was destroyed. The loss derailed plans that were then in the pipeline for an official history of the Emigration Department.

However, although virtually all of the Department’s internal records, including the applications and travel records of assisted emigrants, have been lost, much of its publicity material has survived. Evidence of its aims, methods and achievements can also be found in the published material we hold in our library and periodicals collections, while photographs in our archives document some of the groups assisted and the places they would have encountered on their journeys with The Salvation Army to new homes. The result of our work to unearth these records is a new subject guide on migration. This is the third subject guide we have produced and it is available now here and on our resources page.

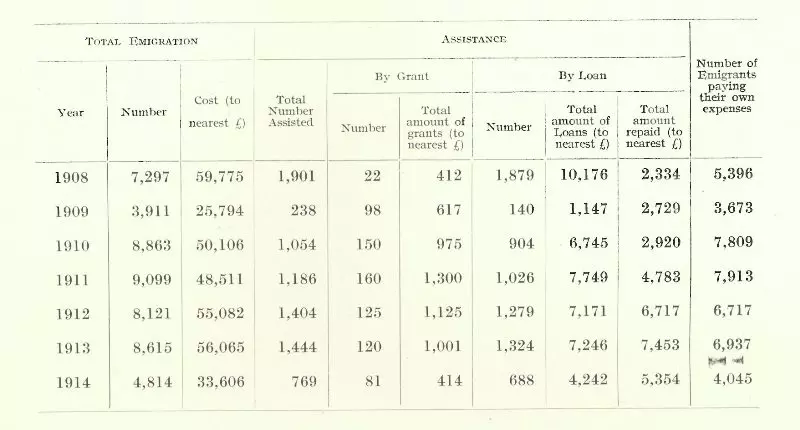

The guide provides a chronological overview of the stages of Salvation Army emigration work. The Salvation Army began tentatively investigating the prospects for assisting emigration as early as 1885 in connection with its rescue work for women and in 1890, William Booth formally incorporated emigration and colonization into his three-stage plan to save what he called the ‘submerged tenth’ of Britain’s population. Although the first two stages of his ‘Darkest England’ scheme, the City Colony and the Farm Colony, were put into practice quite quickly, the third stage, involving emigration, suffered delays. Assisted emigration did not really take off until 1903, while the colonization component of the plan was never accomplished as Booth had envisaged it.When Salvation Army emigration did take off it did so on a grand scale. By 1905 there was sufficient demand for The Salvation Army to charter a vessel to carry a thousand people to Canada ‘under the Army flag’, and statistics from the British Government’s Emigrants’ Information Office show that ‘in five of the seven years between 1908 and 1914 more people were emigrated under the auspices of the Salvation Army than by all the other voluntary bodies combined.’[1] However, as the table below shows, it wasn’t the ‘submerged tenth’ who took the greatest advantage of The Salvation Army’s services: on average 84% of emigrants paid their own fare.

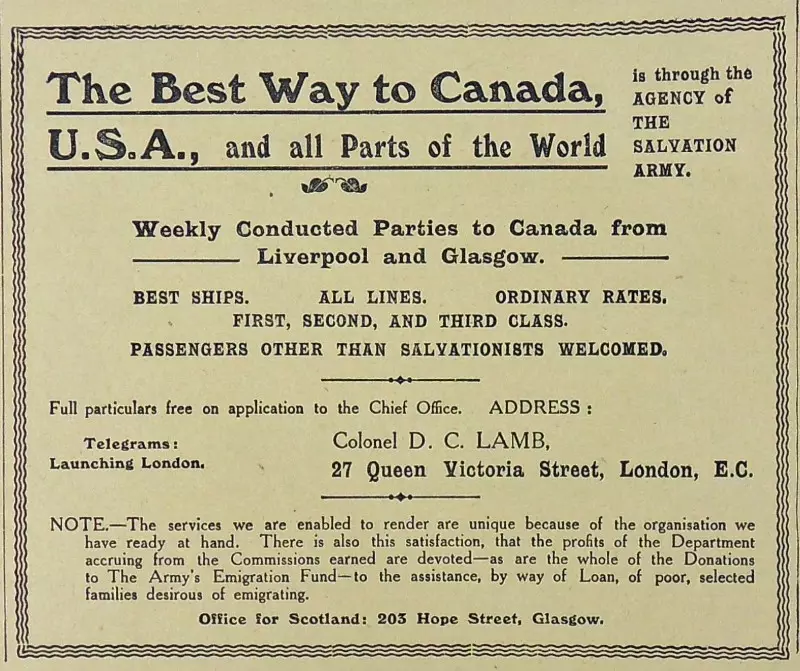

As historian Clive Fleay has said, it is interesting that so many emigrants who could have made their arrangements elsewhere chose to travel with The Salvation Army. What was it that attracted them? The Salvation Army certainly thought it was the enhanced level of care that it put into selecting, assisting and supporting migrants before, during and after their journeys. In 1914 it was said that ‘The care of the modern emigrant has been made almost a fine art—or rather an exact science—by The Salvation Army.’[2] Special features of its emigration service included conducted parties, accompanied throughout their journey by a Salvation Army Officer, and floating labour bureaux.

Canada was the prime destination during the Edwardian period and The Salvation Army encouraged emigrants to settle in rural locations there. Its publicised aim was to bring ‘the landless man to the manless land’. However, the emigration of men was stopped during the First World War and for a time The Salvation Army focussed on the emigration of single women and widows with children. It had considerable pre-war experience of assisting women emigrants but in 1916 it launched a dedicated Women’s Migration Scheme with funding from the Prince of Wales National Relief Fund. This scheme helped 2788 women and children to migrate between 1916 and 1923.In some ways women were seen as more eligible candidates for assisted migration. A contemporary report stated that ‘In the matter of repayment of loans the women show up better than men.’ ‘In one period The Army advanced £25,000 for the payments of passages of single women, of which 90% has been refunded. … This would seem to indicate that women are more faithful in discharging their obligations than men, or that they have profited more through emigrating.’[3]

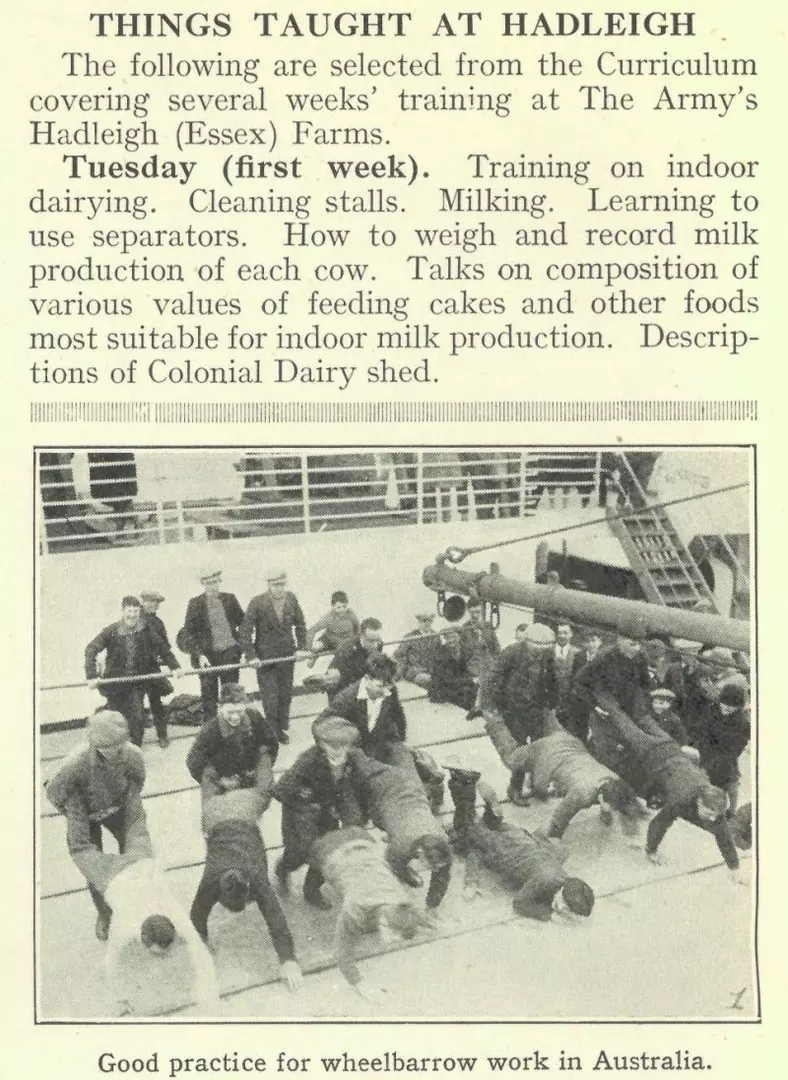

As the 1920s went on, the southern hemisphere began to welcome increasing numbers of Salvation Army emigrants, and young men in search of better job prospects were targeted once more. A new Boy’s Migration Scheme was inaugurated in 1923 and sent many parties to Australia and New Zealand in the course of the decade. Under the scheme, The Salvation Army’s Hadleigh Farm Colony in Essex was entirely turned over to training boys between the ages of 14 and 19 in preparation for agricultural jobs in the Dominions.

The Salvation Army voiced great concern at ‘the perils of idle youth’, suggesting that not only could widespread unemployment adversely affect the moral character of young men but that it presented ‘an economic menace for the future’.[4] While the labour market in the UK at this time was ‘glutted’, opportunities apparently abounded in the British Empire Dominions: ‘boys are wanted overseas; indeed, the demand is greatly in excess of those that emigrate.’[5] Agricultural work, as well as being plentiful, had numerous benefits, in the eyes of The Salvation Army, over the kinds of work available in the UK. Farming was healthy for body and mind, and gave boys the opportunity to become ‘proprietors and responsible citizens and national assets and models and object-lessons for others to follow’.[6] Salvation Army reports indicate that young men did well under the scheme, with most able to repay their loans within one to two years.

One of many ways The Salvation Army advertised its emigration schemes of the 1920s was through magic lantern shows. We have one complete show in our collection with its accompanying presentation text. The gallery below contains a selection of images from this show along with other publicity material in our archives relating to the Emigration Department. For further information on the history of Salvation Army emigration, please do take a look at our subject guide.

Ruth

November 2015

[1] Fleay, Clive, ‘The Salvation Army and Emigration 1890-1914’, Middlesex Polytechnic History Journal, Vol.1, June 1980, p.64.

[2] The Salvation Army Year Book 1914, p.62.

[3] EM/1/1 'Empire Reconstruction: The Work of The Salvation Army Emigration-Colonization Department 1903-1921', p.10.

[4] ‘The Perils of Idle Youth’, The War Cry, 10 March 1923, p.3.

[5] The Salvation Army Year Book 1926, p.37.

[6] HFC/1/7 ‘Hadleigh Colony and Overseas Settlement’, lantern show presentation text, p.5.

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

“Almost demented with hunger and fear:” Easter 1916

The events of the Easter Rising against British rule in Ireland were widely covered in the British press, and the periodicals of The Salvation Army prove to be no exception...

From bad to worse: The Salvation Army in communist Czechoslovakia

Papers from our archive detail the problems The Salvation Army experienced following the nationalisation of churches in Czechoslovakia in 1949 ...

The Salvation Army in Post-War Germany

Papers in our archive shed light on the work of The Salvation Army in Germany during the Second World War ...

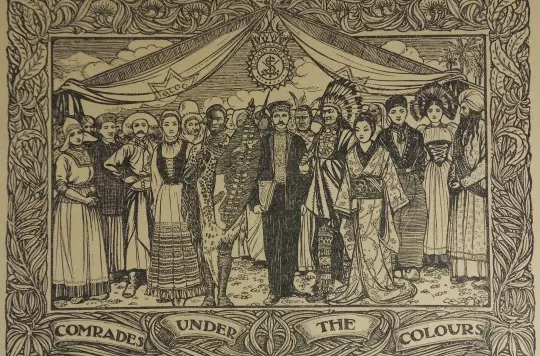

‘Comrades under the Colours’: International Congresses

The Salvation Army's first International Congress was held in 1886 to celebrate the organisation's 21st anniversary ...