International Heritage Centre blog

Two hundred boxes

Two hundred boxes

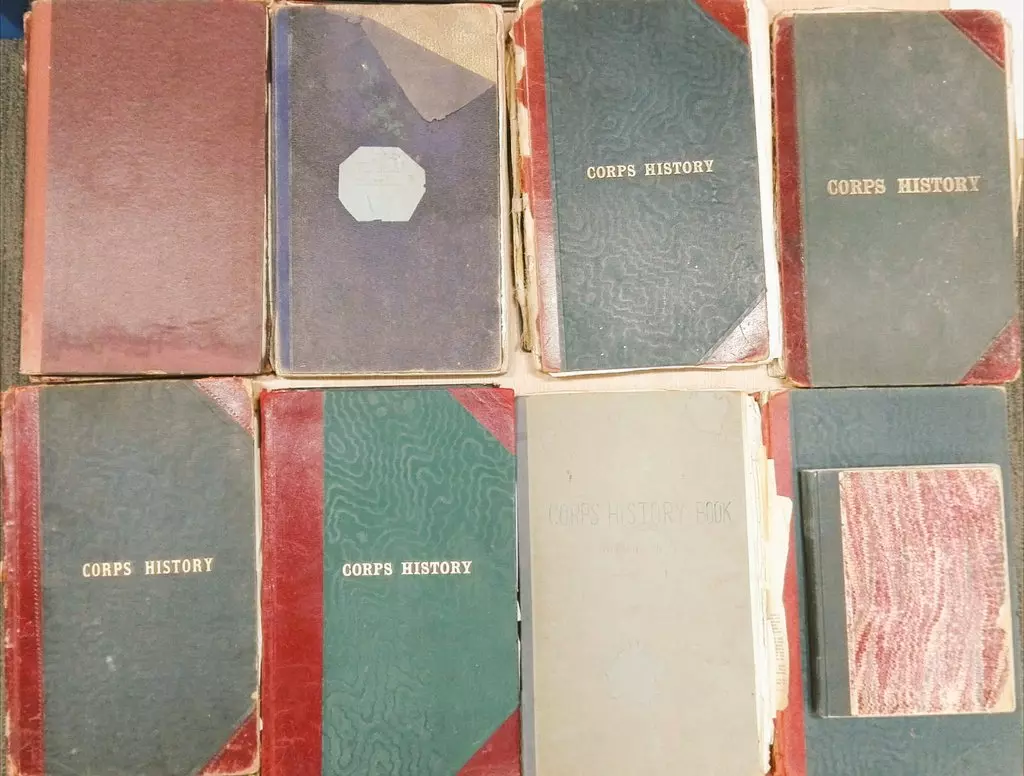

The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre has over two hundred boxes containing material from British corps (churches). The content of these boxes is arranged alphabetically from Abbey Wood Corps through to York Corps. The majority of the material consists of books, documents and photographs. Practically all of the books are the official records of the Corps in question: membership registers, financial accounts and local history.

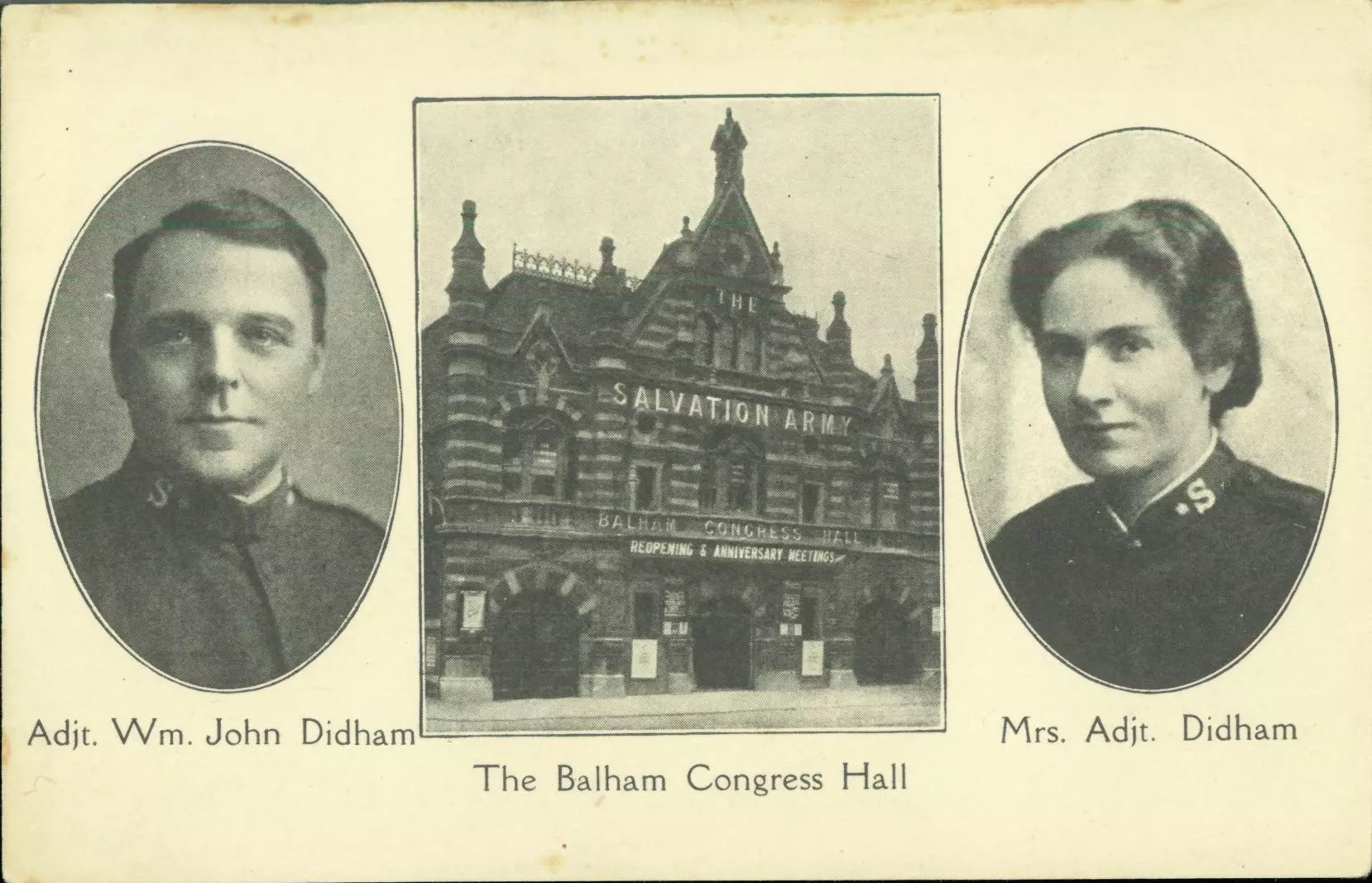

The documents can be anything from official legal papers through to scribbled notes: for example, place of worship registration documents through to hand written lists of the stalls at the Corps Sale of Work (Bazaar). The photographs provide a fascinating visual history of Corps life. For instance, in the early years of the movement it was commonplace for Corps Officers to provide picture postcards of themselves.

I was given the task of going through all of this material in order to update our records, describe the content in greater detail and generally tidy up what had become overflowing boxes of material. It was a lengthy process but it did allow me to engage with these artefacts. Amidst the history contained in these boxes, three modern day issues were to be found: freedom of information, religious tolerance and feminism.

Freedom of information

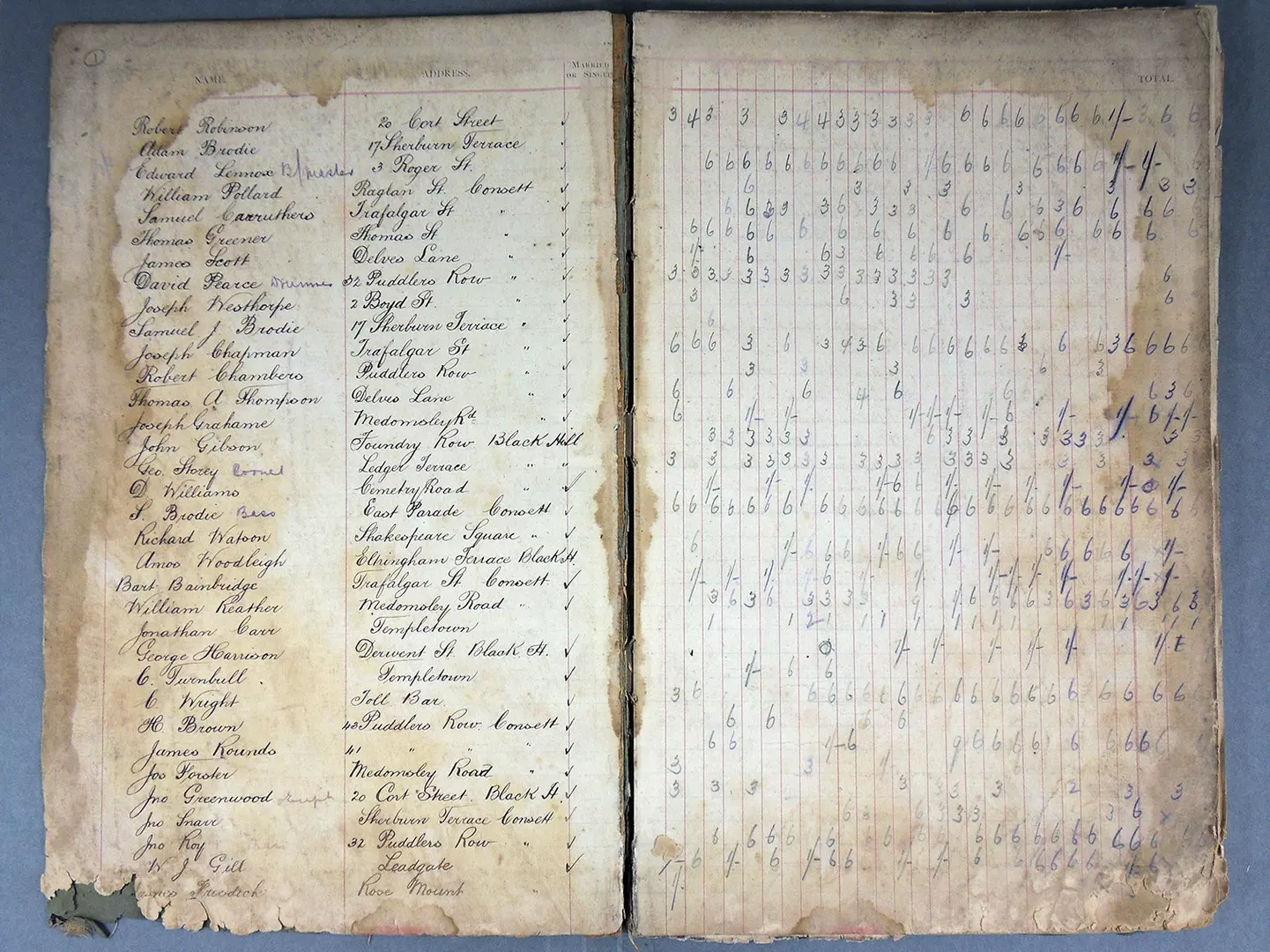

Records of Salvation Army officers (ministers) are kept centrally at the Heritage Centre. We have a reasonably comprehensive set of officer records. The main gaps are of officers from the very early days of the movement and also of officers who resigned their commission. Records of Salvation Army soldiers (members) are kept locally. These records are far from comprehensive. Old registers appear to have often been misplaced or inadvertently destroyed rather than kept safe for future research. However, some of these registers have been sent to the Heritage Centre. They are stored in the two hundred boxes already mentioned.

We receive a large number of enquiries; covering a wide range of issues. These enquiries range from the fairly mundane – such as the details of a trombone that was made by The Salvation Army decades ago – through to information about long lost family members. The Heritage Centre exists to make information available and is very much part of the freedom of information culture (even though the Freedom of Information legislation itself only applies to public bodies). However, those officer records and membership registers can sometimes provide a challenge. From a freedom of information viewpoint, they are an often impressive source of personal information: names, family details, dates and places. At the same time, care has to be taken to ensure that freedom of information is balanced by the important – and legal – requirements of data protection. The excitement of finding an answer to an enquiry is sometimes quashed because we are unable to pass on the information.

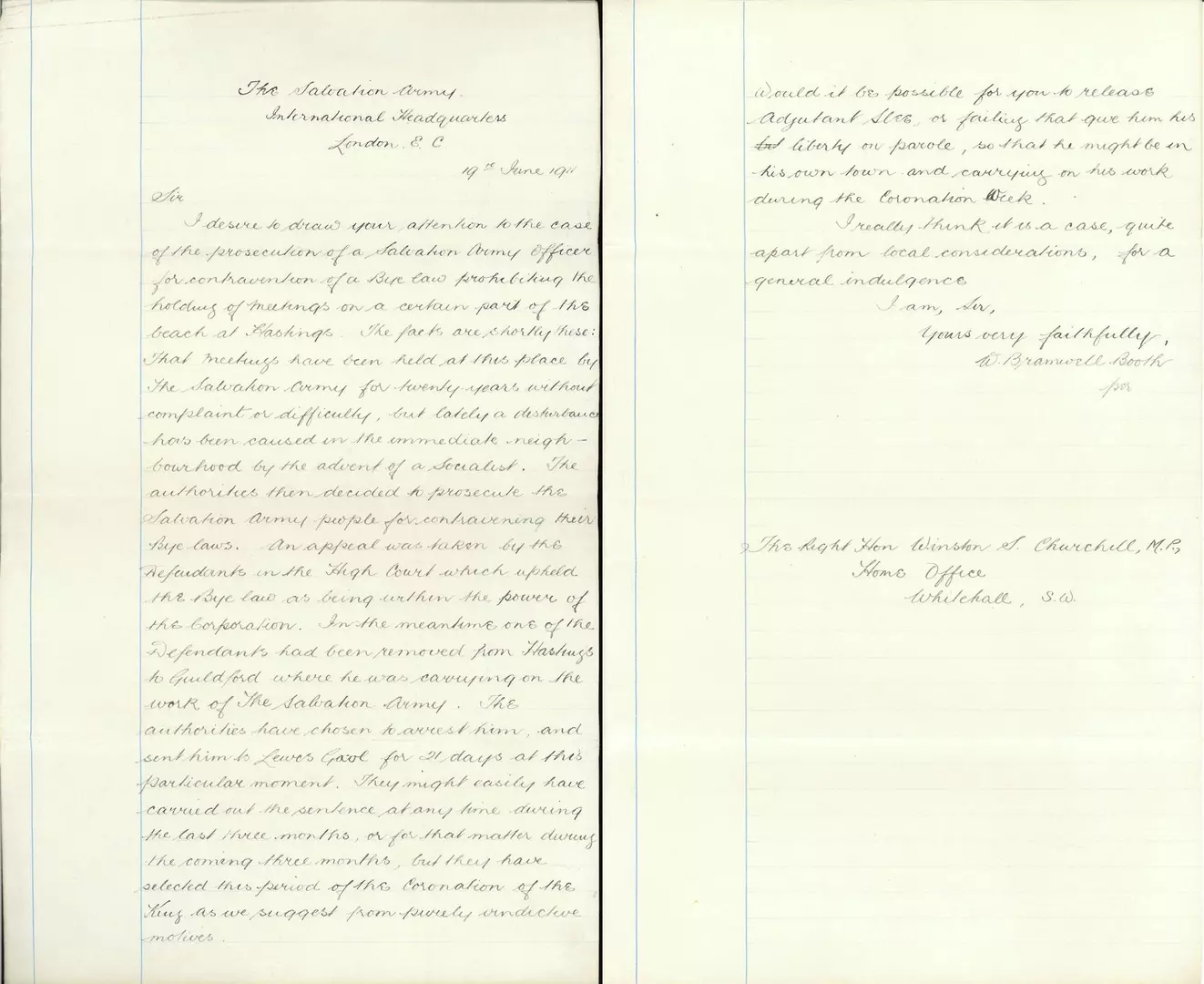

Freedom of the streets

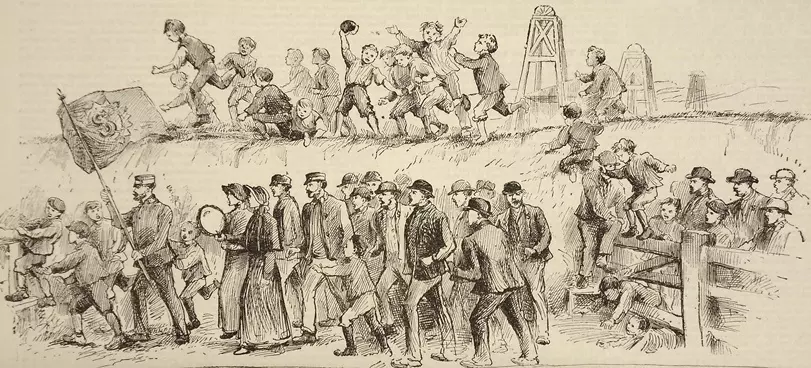

Amidst some rather humdrum paperwork, I came across a letter from Bramwell Booth to Winston Churchill. It was in very good condition. I can only assume that it was a copy of the actual letter that was sent to Churchill. The Corps in Hastings had been subject to rioting. It was not alone. A number of Corps – mainly in southern England – were subjected to some pretty rough and dangerous treatment during the early years of the movement. Nigel Bovey has written a book – Blood on The Flag – in which he tells the story of this persecution.

Rioting was not unusual in Victorian England. This includes riots associated with religious matters, such as the reintegration of Roman Catholicism within British society or the growth of the Anglo Catholic movement within the Church of England. You can argue that the riots against The Salvation Army were counter-productive. Nothing unites a fledgling movement more than opposition; added to which, Booth understood the importance of publicity. However, this was no minor issue. One officer, Captain Susannah Beatty, is sometimes regarded as the first Salvation Army martyr, as her death at the age of 39 ‘was at least accelerated by the rough treatment received at some of her stations.'

Bramwell’s letter to Churchill – who had an appointment within the Home Office at that time – demanded protection under the law and for the right to hold religious meetings in public: the freedom of the streets. In due course this was granted and the rioting against The Salvation Army ceased. These rights, that were won so long ago, cannot be taken for granted. Indeed, General Shaw Clifton refers to two occasions towards the end of the twentieth century when action had to be taken to defend these rights. The story is recounted in “Something Better” by Shaw Clifton (see p199).

Freedom from prejudice

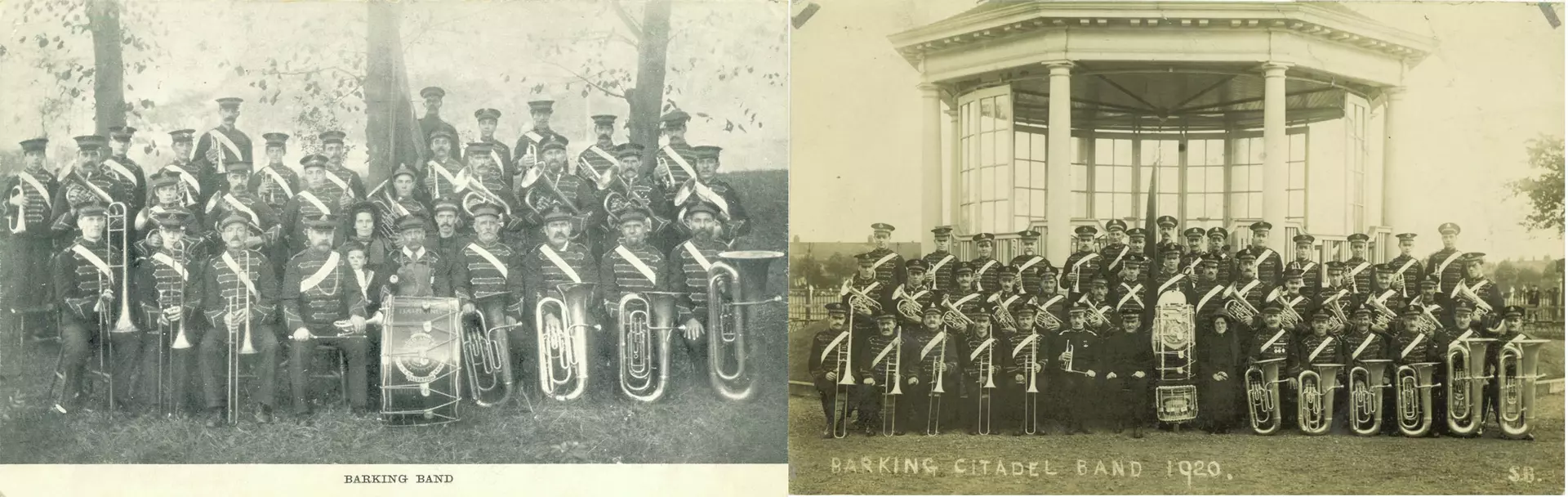

The photographs were a joy to catalogue. I was transported back in time as I perused a wide range of subjects: all related to the local Corps. I had not catalogued many boxes before a strong pattern began to emerge. There was one subject more than any other that was the focus of the camera. Photograph after photograph after photograph was of the band. The visual history of the British Salvation Army Corps is awash with images of the band. This will not be a surprise to many people. Whenever the general public think of The Salvation Army they usually think of uniforms, helping people and the ubiquitous brass band.

The quantity of the images was not matched by the creativity of the cameraman. A large proportion of the photographs had been set up in exactly the same way: bass drum on its side in the centre, bandmaster and corps officers sat behind, bandsmen standing in three or four rows, forming the backcloth. Occasionally someone had the forethought to place the date and the name of the band on a board leaning against the drum. The brass band, together with soccer, was one of the great working class success stories of the nineteenth century. It was surprising to see that quite small communities were able to boast a fairly large Salvation Army brass band.

The photographs shared one major omission: women. Apart from the wife of the officer couple, there were no other women to be seen in the vast majority of the photographs. Banding was an all-male activity, an all-male club. This is particularly surprising in a movement that promoted gender equality in its founding document and that was co-founded by Catherine Booth, a feminist before her time. Whatever the reasons – and probably there were a number – it wasn’t until the second half of the twentieth century that this practice, this prejudice began to be addressed.

Mel

April 2020

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

Guest blog: Location, Location, Location

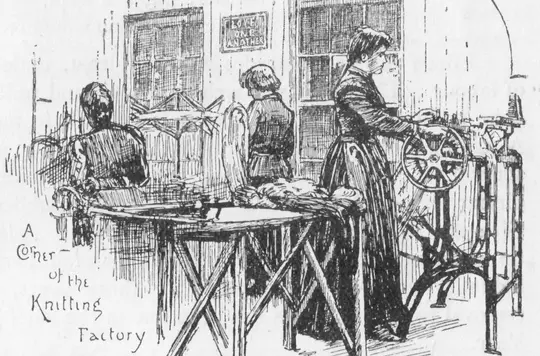

This month we have a guest blog from our Birkbeck University intern, Imogen, exploring the who, what and why of The Salvation Army's east end Knitting Home...

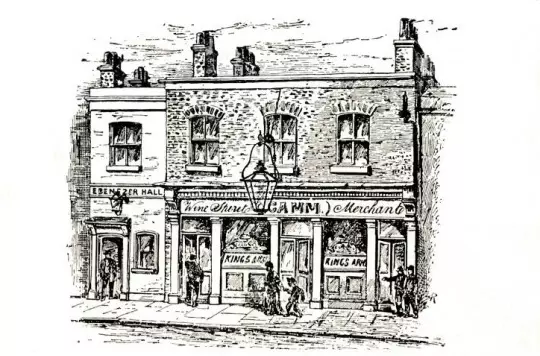

‘Our own private ball of sun’: archives shed new light on 5 Ravensworth Terrace

Since recording 'A House Through Time', new records have come to light which add to our understanding of this house’s rich history...

Profitable Reading? Fiction in Nineteenth-Century Salvation Army Periodicals

From its beginnings as the Christian Mission, The Salvation Army was (and still is) a prolific publisher...

Women's History Month 2020: A Collaborative Approach

Each year Women’s History Month inspires a host of events from exhibitions and talks, to defiant marches and historic walks...