Opposition

The Salvation Army's expansion brought it to the attention of a wider audience, not all of it appreciative. Criticism came from established churches, particularly the Anglican Church; organised groups, forming 'Skeleton Armies'; and local authorities, who regarded open-air meetings as obstructions of public space.

Early critics

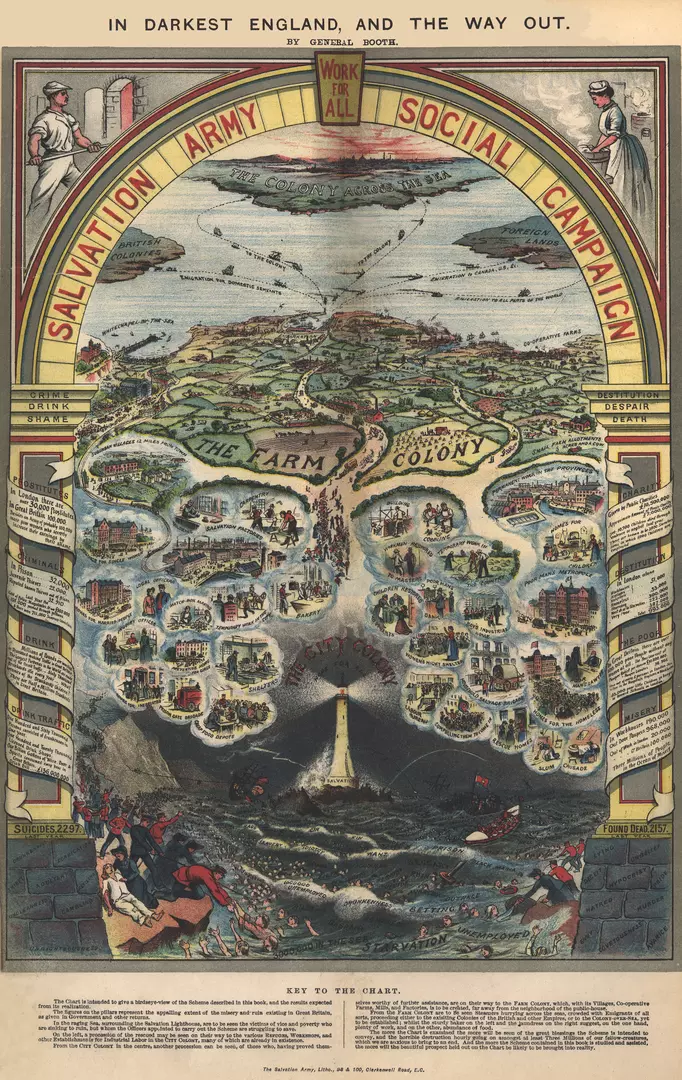

As The Salvation Army expanded in the late nineteenth century a number of pamphlets appeared criticising the movement, including Social Diseases and Worse Remedies by the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley. He attacked The Salvation Army’s ‘religious fanaticism’ and the autocracy of the General but the pamphlet’s main criticism was of Booth’s ‘In Darkest England’ scheme. Huxley was only the most prominent of a number of secular detractors, many of whom (including some leading newspapers) accused William Booth of financial impropriety in the management of various social work funds. Criticism also came from the Anglican Church, whose senior clergy had deep reservations about The Salvation Army’s forms of worship, which one bishop dismissed as having ‘ludicrous stage properties.’ Bishops also made accusations of sexual immorality at Salvation Army meetings but these were found to be groundless.

The Skeleton Army

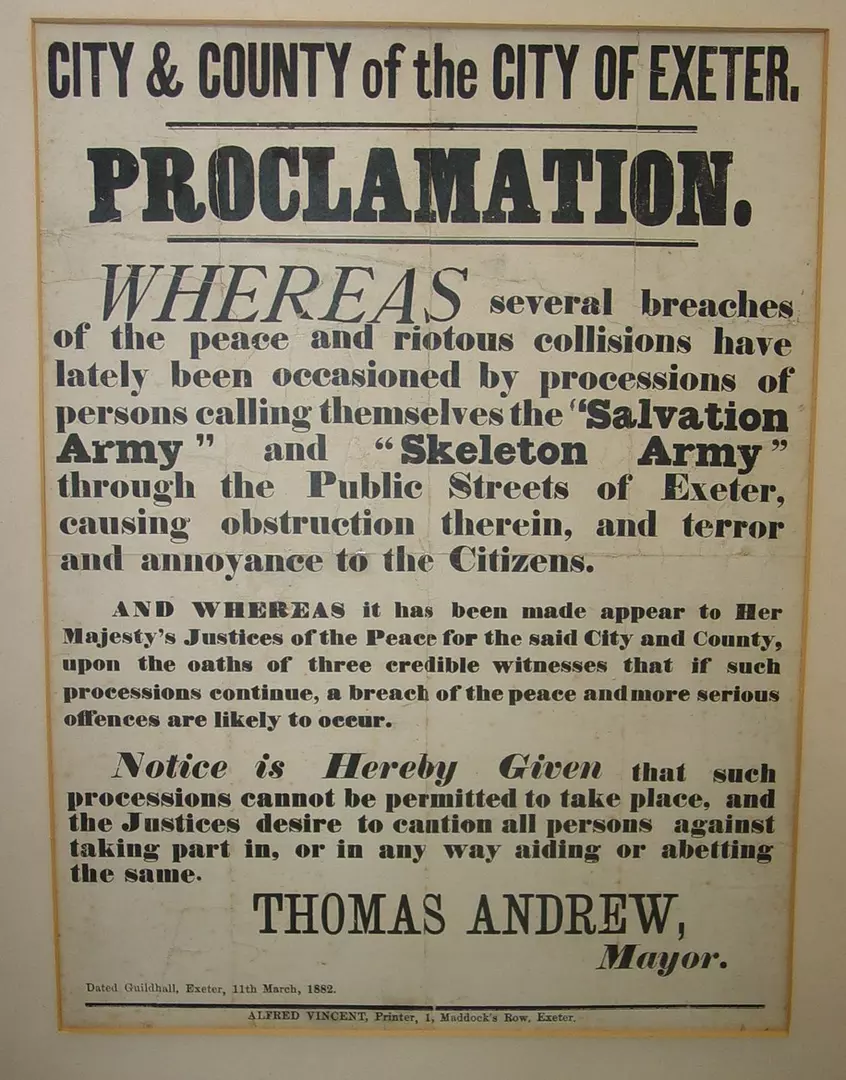

In the 1880s small local groups began to organize themselves against the spread of the Army; their attacks on Salvationists were often treated leniently by police and magistrates. Some of these called themselves ‘skeleton armies’ and their attacks on Salvationists, such as singing obscene versions of Salvation Army songs, throwing rotten food or daubing meetings halls with tar, often formed part of a tradition of ritualised protest that was designed to humiliate rather than to physically injure. Violence was often directed at instruments and flags. Some local authorities and magistrates tacitly sanctioned or even openly supported violence against Salvationists.

Pin badges like this one were worn by some ‘Skeletons’ as a sign of their allegiance.

Imprisonment

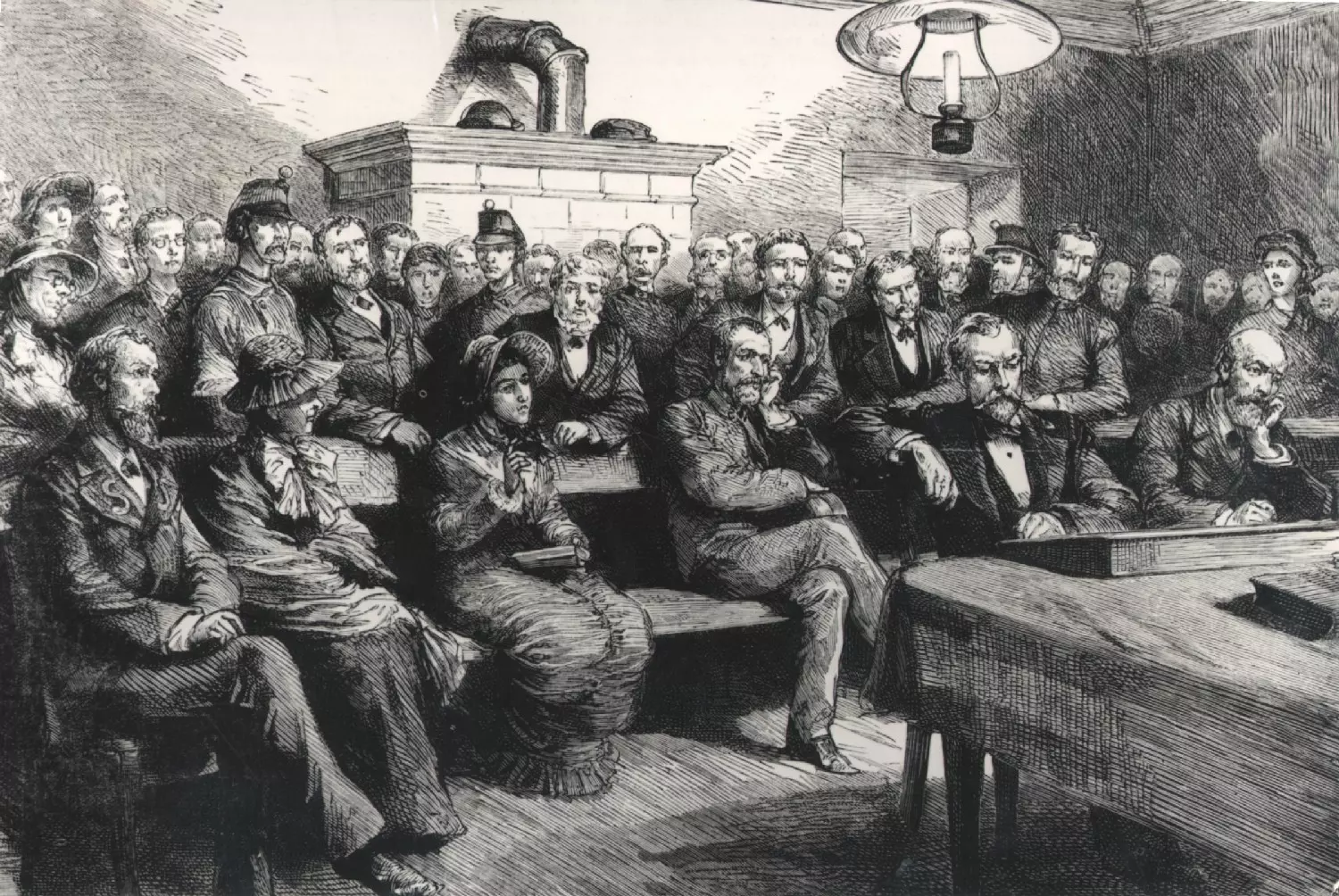

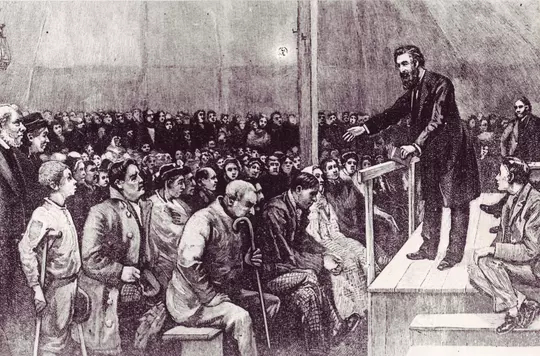

During the 1880s a number of local authorities came to regard open-air meetings as obstructions of public space. Especially in the resort towns of the English south coast, where publicans and hoteliers felt that The Salvation Army’s open-air meetings and brass bands would damage the tourist trade. Salvation Army officers were instructed not to pay fines and many were imprisoned. Between 1886 and 1888 more than 20 Salvationists in Torquay received short prison sentences for breaching a law prohibiting processions on Sundays with musical instruments. In October 1889 more than 1000 Salvationists attended a 'great demonstration of liberty' held in the Hampshire village of Whitchurch. This was a protest against the fining and imprisonment, since May, of more than 90 Salvationists for obstructing the market square. The organisers of this event were charged with unlawful assembly but were found not guilty by a Queen's Bench jury in July 1890. This set a legal precedent for public processions.

These two pieces of bread were issued to Salvationists when imprisoned in 1889 and 1892.

Riots

Legal challenges to The Salvation Army went hand-in-hand with more serious outbreaks of violence. Local authorities and magistrates tacitly sanctioned or even openly supported violence against Salvationists. Riots occurred at Sheffield, Exeter and Worthing. One officer, Captain Susannah Beatty, is sometimes regarded as the first Salvation Army martyr, as her death at the age of 39 'was at least accelerated by the rough treatment received at some of her stations'. The most vituperative opposition of this kind came at Eastbourne in Sussex. Following the opening of a Corps there in 1890, the local authorities received complaints that The Salvation Army’s meetings would be injurious to ‘the comfort of visitors.’ Salvationists began to be repeatedly charged with public order offences. When large groups arrived in Eastbourne to support the imprisoned Salvationists, they were attacked by large mobs or were themselves prosecuted. Violence against Salvationists became common and the authorities refused to prosecute The Salvation Army’s antagonists. The vehemence of the local authorities’ persecution led Parliament to intervene in 1892 to give a legal basis to their open-air meetings.

Global opposition

Opposition was also met in other countries. Many new territories were initially hostile to Salvationist missionaries; Swiss authorities suspended The Salvation Army in 1883 and William Booth’s daughter, Katie [later Catherine Booth-Clibborn], was briefly imprisoned. Violence was not uncommon and a number of Salvationists were martyred, including Louis Jeanmonod who was murdered guarding a Salvation Army meeting in Paris on 4 February 1886. The Salvation Army was banned outright by anti-religious Marxist governments in Russia (1923) and China (1953). Although The Salvation Army was invited back into Russia in 1991 following the collapse of the USSR, it was subsequently banned as a ‘paramilitary organisation’ due to its uniforms and militaristic language. This decision was overturned by the European Court of Human Rights in 2006.

Who are The Salvation Army?

Discover the origins, beliefs and symbols of The Salvation Army.

People

Find out more about The Salvation Army’s founders, leaders and early pioneers.

Music

Find out about the role that music and song plays within The Salvation Army.

Social work

Discover the origins and history of The Salvation Army’s social work.