'Like a bird on the water'

The Salvation Navy, 1885-1888

The formation of the Salvation Navy was providential. In 1884 William Booth mentioned the possibility of setting up a Salvation Navy and in May of the following year he was offered a 100ft steam yacht by one of his wealthy supporters.

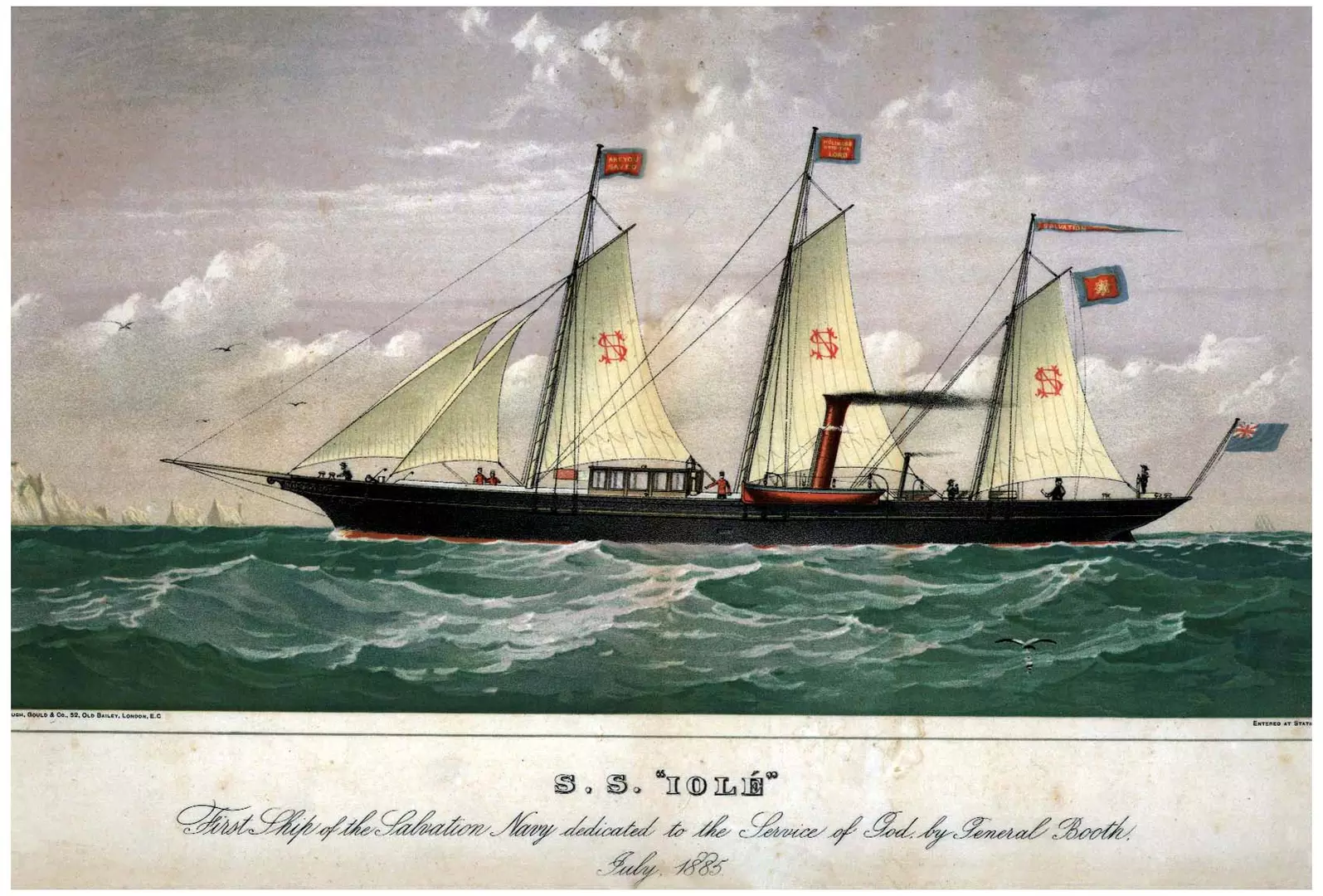

John Cory, a coal broker and ship-owner from Cardiff, had bought the Iole as a pleasure yacht for his wife who had sailed it for a month but who was nervous of committing to sailing for leisure. So Cory offered the yacht to Booth and his Salvation Army. Upon hearing that some consideration had already been given to a Salvation Navy, Cory said that ‘“Evidently God has been ordering things”. In June 1885 the yacht was lying in Shoreham Harbour being prepared for her launch as the flagship of the Salvation Navy in August. Her three masts flew the Salvation Army colours of red, blue and yellow, alongside flags bearing the words ‘Are you Saved’ and ‘Holiness unto the Lord’. Her sails carried the monogram ‘SN’ for Salvation Navy. The Iole was described by her first commander as looking ‘like a bird on the water.’

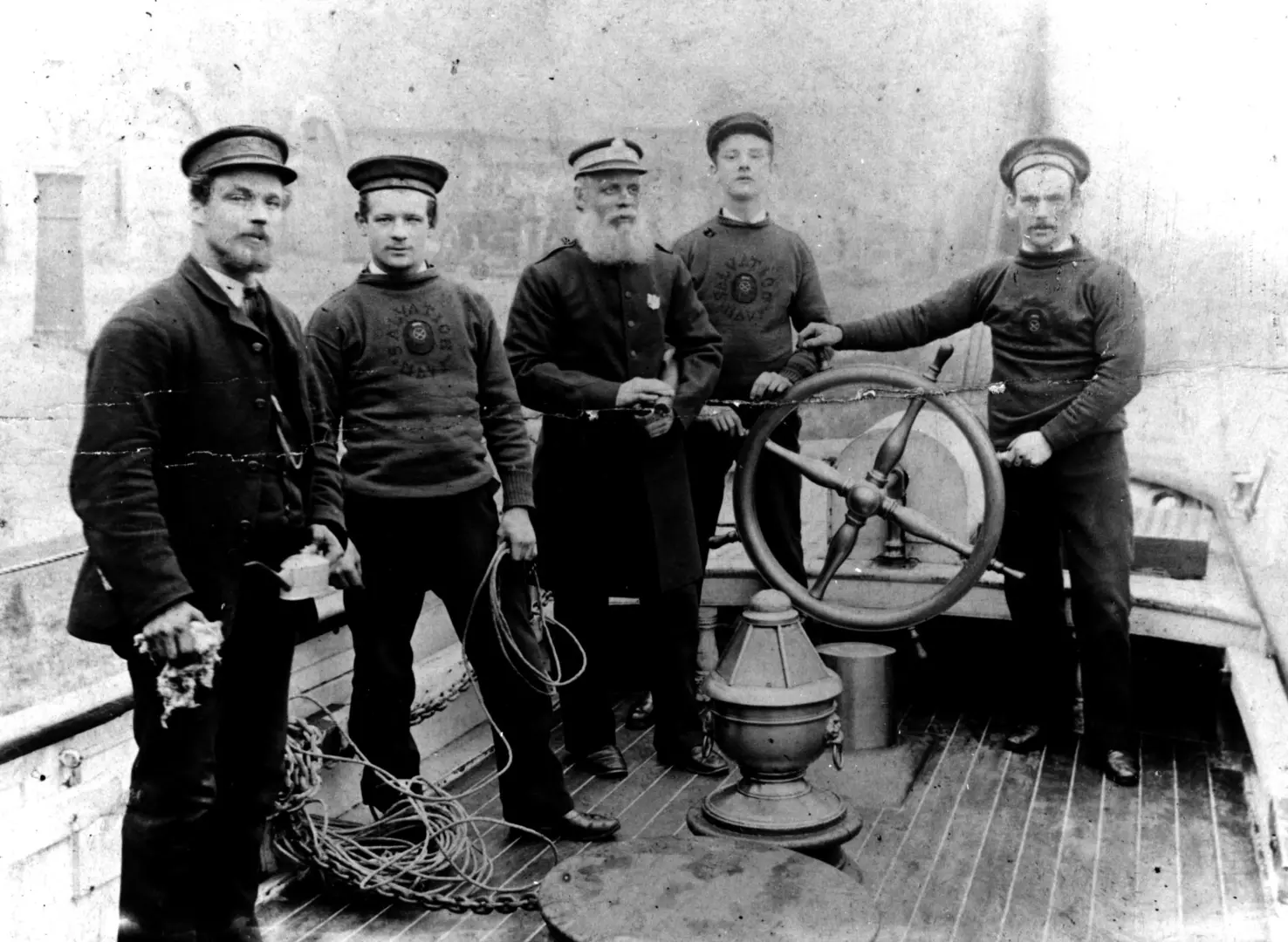

The SS Iole required a captain and a crew of four. This was assembled from officers and members of the Salvation Army with nautical backgrounds, with The War Cry advertising for a second-class engineer. The command of the Iole was given to Staff-Captain Sherrington Foster (also known as ‘ex-Admiral’ Foster) who had been a ship’s captain and master of the Hartlepool lifeboat. The captain was Sailor Fielder, who had been master of a ship for nine years. A photograph, probably from 1886, shows Admiral Foster with his crew. The use of a pleasure yacht for an evangelical mission did not go unremarked and she was described as “a little gem, perfect in all her appointments, which are, indeed, almost too luxurious for salvationists. We fancy our comrades have little use for the pier-glass and sofas which adorn the cabins, but the piano fitted to the saloon can hardly come amiss to them.”

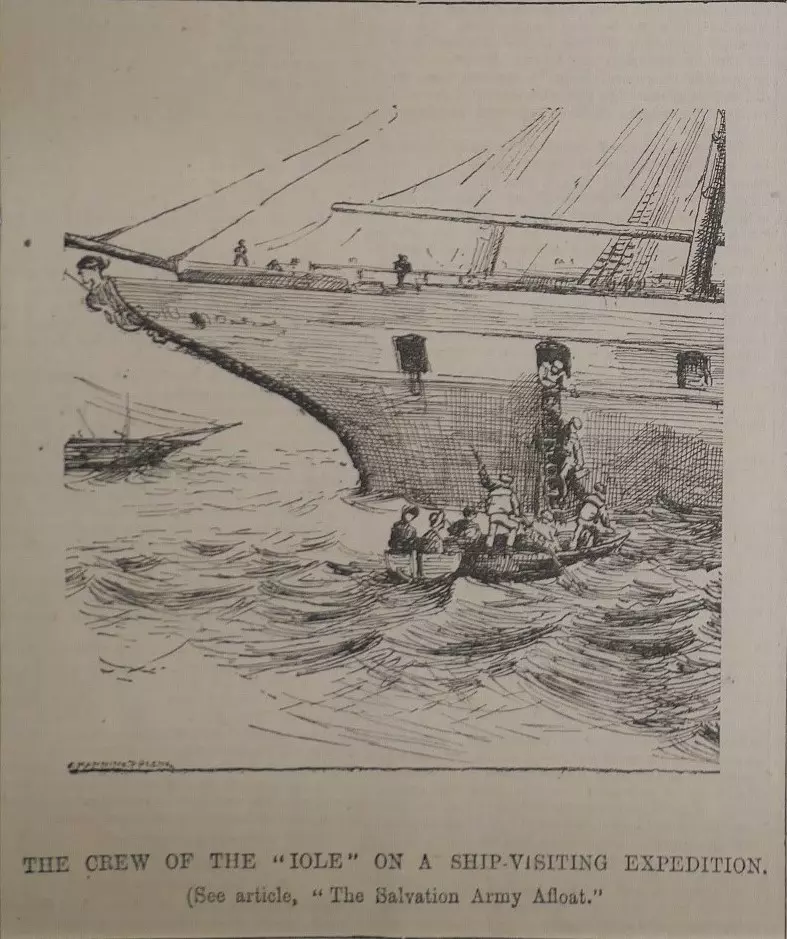

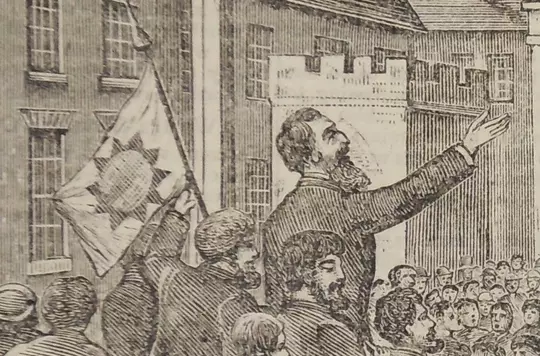

The purpose of the Salvation Navy was “to do for those who go to sea what The Army does for those attending no place of worship on land. […] to visit every fishing town and seaport village along the English, Irish, Scotch and Welsh coast, boarding every vessel when lying in any roadstead, giving Bibles and good books, preaching Christ, and doing all in our power to get the sailors and fishermen of our country converted.” (We know of the Salvation Navy’s activity around the English and Wales coast but no evidence has been found of their work in Scotland or Ireland). The War Cry put it more dramatically- “We shall hurry up after every poor blue jacket who has not another friend in the world, and rush in with Salvation to every fisherman’s boat and every bargeman’s keel.” A pamphlet of “Salvation Navy Songs” was published and, as The Salvation War 1885 described, in “the summer months vast crowds were assembled on pier and beach, whilst from the deck of the little vessel the yacht's crew, assisted by the local Corps where there was one, proclaimed salvation to all sorts and conditions of men.”

The Salvation Navy was not the first initiative to evangelise to coastal communities as several missions to seamen had been established earlier in the C19th. There had even been an earlier Salvation Navy set up by an Admiral John Blore and unconnected to General Booth’s Salvation Army.

In late August the Iole was visiting Jersey I Corps in the Channel Islands and then sailed on to the Isle of Wight. The yacht spent the winter of 1885 “visiting the ports in the English channel” and in January 1886 she was on the Cornish coast visiting Porth Leven, Falmouth, Fowey and Polruan. By March she was in Exeter. Attempts were made to acquire a second ship for the fleet, as Mildred Duff, a Salvationist from a wealthy family (who would later become an officer and a prominent Salvation Army author), was trying to buy a 70ton yacht, the ‘Asprey’ in Gosport in April 1886. The sale appears to have fallen through and there was only ever one official ship in the Salvation Navy. Naval Brigades were, however, established in the communities it worked amongst. Ships whose captains and crews were made up of Salvationist were encouraged to fly the Salvation Army colours. The Navy planned to “enrol all our sea-going soldiers in Naval Brigades, who shall labour specially for the salvation of their fellows of the deep.” A Brigade could comprise as little as two sailors, with a leaders identified as Bosun. On one occasional William Booth launched a Naval Brigade at Plymouth with a dozen ships flying Army colours.

By the summer the Iole was conducting an evangelical campaign in East Anglican ports, including Lowestoft in May and Ipswich in June. Disaster then struck the Salvation Navy as the Iole was sailing to hold a series of meetings with Salvationists in Hull. On the evening of 11 June 1886, she struck a sandback in the Humber (possibly snagging on wreckage of ship that had run aground a few weeks earlier). The ship began taking on water and the crew had to escape on the lifeboat and row ashore. It was reported that, the next morning, “at dead low water only two or three feet of the Iole’s funnel was to be seen”. One Salvationist in Hull wrote in a letter that

“the ‘Iole’ has sunk to the bottom of the Humber- as she was coming along she got on to a Sand Bank & sunk at once – all the crew were saved- Body & Soul Thank God […] There were 7 on board […] All except one has lost all belonging to them. Nothing was saved except their lives […] The people are most sympathizing & are buying clothes etc. for them- one of the crew said in his testimony on Sunday that although his bed & his clothes etc. etc. were lying at the bottom of the Humber yet he was happy because he had not lost Jesus- though to the world it would seem he had lost all- yet he had all in Jesus for He is all & in all! – I thought it was so beautiful.”.

This Salvationist, Amy Beddington, would go on to marry one of the shipwrecked crew and they would both become officers. ‘Ex-Admiral’ Foster seems to have stayed in Yorkshire and begun an evangelical campaign through the county, before dying while addressing the meeting at Easingwold in September 1886.

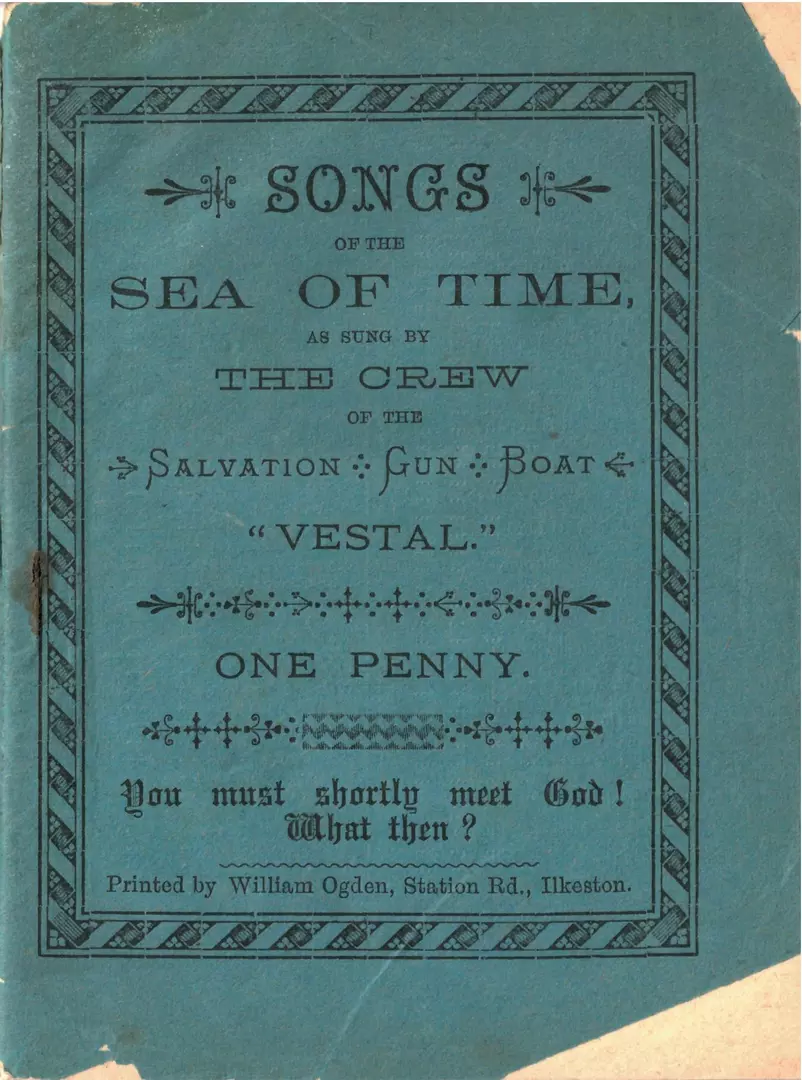

The Salvation Navy was without a ship for some 7 months until John Cory again came to the rescue and gave an 82ft racing yacht, the Vestal, to Booth. This became known as the ‘Salvation Gun-Boat’. In February 1887 the Vestal was in a shipyard at Southampton ‘awaiting orders.’ However, these orders took some time to take effect, as the Vestal was recorded as “still lying in the mud” in late March and had to await significant repairs costing £120 before she could be launched on 5 April, by which time she had been “fitted up below to seat 120 persons at a meeting”. It’s first captain was Abbot Taylor, various described as “formerly a Torbay fisherman” and “late skipper of a Brixham smack”. The Vestal continued the evangelical work of the Iole for several months, visiting Bridport and Watchet in July. She spent the winter of 1887/88 along the south Wales coast, arriving in Cardiff from Newport on 23 December and holding meetings in West Bute dock. Visiting Swansea in February where “there was a demonstration on board the vessel [in the North Dock], when to a large crowd the crew spoke with considerable fervour”. In late February the Vestal was at Lanelli. An 1888 photograph shows Taylor and his crew on board ship at the time of this south Wales campaign.

These successful campaigns were followed by another disaster in February 1888 when the Vestal was struck by another vessel in the Thames, “considerably damaging the yacht”. It seems that the ship, and her crew, never fully recovered. Letters from the captain show problems setting in, with more repairs needed at Shoreham in June 1888 and, despite intentions to sail to Cornwall, appears to have been stuck on the Sussex coast in the summer- it was at Newhaven in May- due to the illness of Captain Taylor. Reports in The War Cry also show a shortage of crew, with adverts asking for: “Captain and Mate, Certificated, and with a good knowledge of the Coast, well saved and able to lead Salvation meetings. Also two Able-bodied Seamen, One Ordinary Seaman, a Cook and Steward. Must in each case be well saved men.”

The last known report from the Vestal is in October 1888 when Captain Taylor was preaching about their work at the corps in East Grinstead, while the ship was lying at Portslade. Which may imply that the coastal work was not at that time taking place and that the Vestal had been limiting its activities to the Sussex coast since May. Some later sources say that the Vestal was given to The Salvation Army in Sweden- the Frälsningsarmén- in 1890. In any case no further records have been found of the work of The Salvation Navy in British waters.

International Heritage Centre

Telling the story of The Salvation Army from its origins in the 1860s to today.

Virtual Heritage Centre

Visit our London museum virtually.

People

Find out more about The Salvation Army’s founders, leaders and early pioneers.

Early pioneers

Find out about the achievements of some of The Salvation Army's earliest recruits.