Article of the week: A year in the life of Florence Booth

5 March 2022

To mark International Women’s Day (8 March) Chloe Wilson explores the diary of an influential Army leader

FROM the origins of The Christian Mission to uniform, musical instruments and overseas ministry, the museum at the International Heritage Centre provides a wide-ranging perspective on The Salvation Army’s history and heritage. But ever since my first step inside, the Social Work section has been my favourite. Relics from the Hadleigh Farm Colony, the Darkest England initiative and the Strawberry Field children’s home tell stories of the Army’s charitable campaigns from the early 1880s. And within the Rescue Work cabinet resides a manuscript diary written by Florence Booth, pioneering leader of The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Work from 1884–1912.

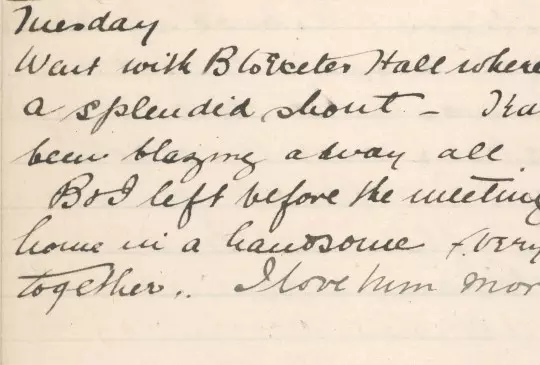

During the Covid-19 pandemic I had the opportunity to explore the contents of this diary in more detail. Turning open the first page, I joined Florence in the suburbs of London on 1 January 1885 to learn, in her own words, about this chapter of her life.

In the style of a new year’s resolution, Florence pledges her first penned words of the year as ‘Vegetarianism[.] A year of faith & hope & love’, immediately signposting her dedication to self-improvement, her heart-warming optimism and her compassionate outlook upon the world. Florence embodied these values and, as the diary develops, we witness her active discipleship, waking early to carve out individual ‘time with the Lord’ and drawing strength from her faith for leadership, whether at public meetings or in one-to-one encounters.

Florence’s determination and capability shine through in her account of daily duties, consisting primarily of managing social work finances, providing practical support to women’s shelters, finding domestic service positions for ‘rescued’ girls and documenting their experiences – all the while caring for two children under the age of three.

However, this diary reveals its role as a secure space where Florence expresses her innermost emotions, including fears of failure and at times feeling ‘downhearted’ and ‘depressed’. Despite an outward demonstration of competence, in this private channel of thought she exhibits a tendency towards self-consciousness and a lack of confidence, particularly to enthuse and lead others – ‘Oh! How I wish I were a talker that could inspire people.’

In contrast with this emotional candour, at times I was struck by extraordinary lapses in information that led to a sprinkling of surprises throughout the diary. The most prominent being the first indication of her pregnancy on her day of delivery, 21 April 1885: ‘Obliged to send for Mrs Crick after tea – Baby born at 1.15.’ Such inconsistencies emphasise the acutely personal and subjective essence of diaries intended for the author’s eyes rather than as an in-depth and instructive historical record for later readers. While in some contexts this would be seen as a fallibility of the diary as a historical source, identifying the information that Florence chose to include or exclude contributes to our understanding of her character and provides a realistic portrayal of her lived experience.

Illness and death shadow the diary throughout, striking a close chord in the light of our two years of pandemic. As well as the death of Florence’s own mother – just a week before Florence gave birth to her second daughter, Mary – we experience through the diary the emotional burden of the deteriorating health of her mother-in-law, Catherine Booth. From dysentery and seizures to ‘an attack of her heart’, concern for Catherine’s wellbeing peppers the diary, illustrating a pervading fear of illness and the fatality that frequently attended it in Victorian Britain.

This theme strikes in the first few pages of the diary as Florence agonises over the poor health of her daughter, Catherine, and her husband, Bramwell, who are ‘very poorly’ for most of the winter, suffering periodically from colds, coughs and fevers. Catherine, who was their firstborn, would live on to the impressive age of 104, which seems an unlikely achievement given Florence’s descriptions of her health during infancy. In contrast, long days of preaching, late nights and frequent travel seem to have taken their toll on Bramwell, fostering fatigue and illness – and concern from Florence. On 11 February she writes: ‘B still very poorly. Took his breakfast in bed – first time since we have been married.’

Throughout the diary, Florence’s affection and admiration for Bramwell are evident. She repeatedly refers to him as ‘my precious love’ and ‘my darling one’ and declares in November: ‘I love him more and more.’

Another developing relationship that features prominently in the diary is Florence’s friendship with Rebecca Jarrett. Florence introduces us to Rebecca in January when, after a period of illness, Rebecca undergoes a crisis of faith, teetering on the precipice of her former life as a brothel mistress. Florence’s restoration of Rebecca’s faith with an intense evening of prayer and reflection proves pivotal as Rebecca goes on to play a central role in the infamous ‘Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’ exposé of London’s child sex-trafficking scene for which she, Bramwell and WT Stead were put on trial at the Old Bailey.

Through Florence’s diary we receive a blow-by-blow account of the court proceedings from the perspective of one whose life would be changed immeasurably should her husband be convicted. Bramwell was destined to become The Salvation Army’s second General and, as well as supporting a wife and two young children, was already a prominent figure within the Movement. To Florence’s relief Bramwell was acquitted, but Rebecca went on to serve a six-month sentence, throughout which she was visited by Florence, cementing a friendship that would last until Rebecca’s death in 1928.

Through Florence’s diary we witness the responsibilities, rewards and trials of faith, leadership, marriage, motherhood and womanhood in late Victorian Britain. Her diary offers us a unique perspective on the origins and workings of The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social and Rescue Work as well as poignant insights into the personality and life of one of the Army’s most influential women.

- Keep up with the International Heritage Centre blog here

CHLOE IS ARCHIVE ASSISTANT, INTERNATIONAL HERITAGE CENTRE

From the editor

An early look at the editor's comment

Salvationist

Salvationist is a weekly magazine for members and friends of The Salvation Army

The War Cry

The War Cry is packed with features, reviews, mouth-watering recipes, puzzles and more.