International Heritage Centre blog

A closer look at The Salvation Army's London Rescue Homes

A closer look at The Salvation Army's London Rescue Homes

Girls’ Statement Book VII (London) is one of more than a hundred and twenty volumes containing details of women and girls who passed through Salvation Army rescue homes. This particular volume covers all those women admitted to the London receiving home, Brent House, 27-29 Devonshire Road, Hackney, in the period November 1891 to September 1894. On the topic of receiving homes, the Salvation Army's 1916 Orders and Regulations for Social Officers (Women) states that: 'When several Homes are established in the same town or neighbourhood, one Home must be maintained for the first reception of cases of all kinds. Such a Home shall be known as the Receiving Home.' Women were later transferred to whichever rescue home was thought to be most suitable for them. Although the volume contains information on 500 cases, in this blog post we are going to analyse 100 in detail.

The purpose of rescue homes was to ‘rescue’ women from their old lives. Spiritual improvement was seen as paramount, with an emphasis on the women gaining salvation. In addition, skills were taught that would help women find work after leaving the home.

In 75% of the cases analysed, the women were transferred from the receiving home to one of three rescue homes at Oldhill Street, Clapton Square and Amhurst Road, all in and around Hackney / Clapton. The rest went to a number of smaller homes elsewhere in London.

Each woman had to answer the questions ‘How long fallen?’ and ‘Cause of first fall?’. The OED defines a ‘fallen woman’ as ‘a woman who has lost her chastity, honour, or standing, or who has become morally degenerate; (sometimes) a prostitute’, and the statement books struggle to accommodate this range of meanings with its two simple questions. So while 'a very depraved girl… done wrong with boys' (when aged 12) is clearly referring to a loss of chastity, when a 39-year-old married woman dates her fall to twelve months previously, when she ‘…left her husband, who is a very bad man’, she obviously means something quite different. Individual cases vary greatly, as the examples below show.

Physical descriptions

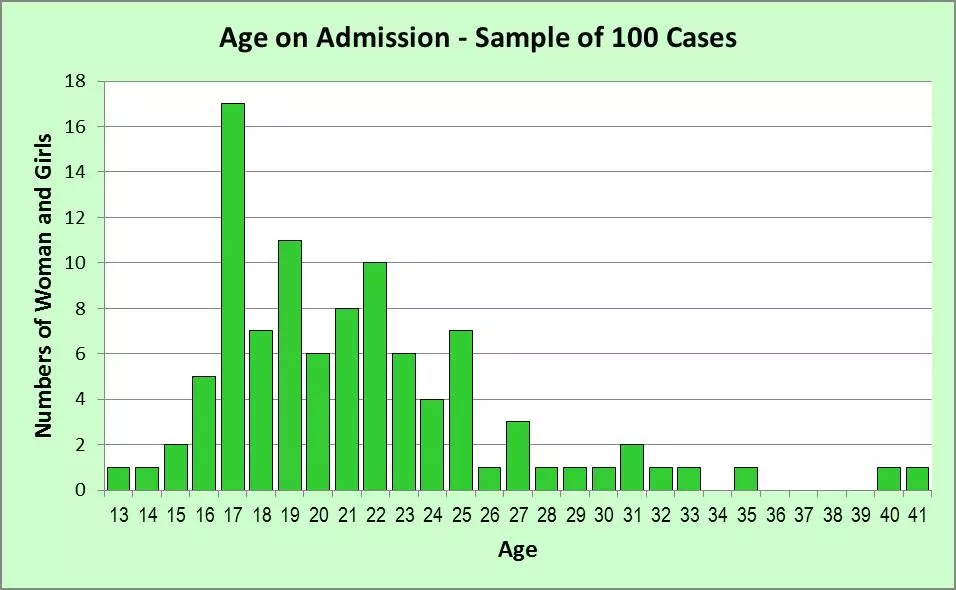

The first case examined in detail was Mabel Broad (14). Sent by her mother in January 1892, she had been a nursemaid with a Mrs Saunders in Brixton, but had stolen three times. Her father (a painter) ‘treated her most cruelly when drunk,’ and had deserted the family. Mabel is described as ‘Small, dark hair and eyes. One eye smaller than the other.’ This prompted me to look for the descriptions of some others. These ranged from ‘tall, fair, nice looking’ and ‘rather short, fair & pretty’ to ‘very low expression’, ‘stout, not a good expression,’ and ‘always looking down’. My favourite, though, is ‘rather ancient looking’ (the woman was 30!) Mabel was sent to our Servants’ Home in Notting Hill, and later went to stay with an aunt in Lissom Grove. Ages As the chart below shows, most were younger women with an average (median) age of 20, but with a number over 30 as well. At least six of the women in the sample were, or had been, married.

Eliza Webb (16) was ‘sent by friends’ as she was ‘a constant source of anxiety to her parents, who are Christians. In their distress they applied to Mrs Booth to take Eliza into a Home, as they could do nothing with her.’ She had already had seven situations in two years, and was described as ‘a dishonest girl.’ She was four months pregnant, having been ‘seduced by a one of the shopmen at her situation.’ Eliza was sent to our Amhurst Road rescue home in Hackney, and from there to a situation as a servant in Forest Gate on £7/year.

Social background

Details of the father’s employment are given in 40% of the 100 cases. This is useful as it gives some idea as to the women’s social background. Most common was labourers (farm, docks and general). These numbered 11. There were also 3 gardeners, 2 carpenters and 2 carters. The others cover a wide range of jobs, including several skilled craftsmen, a book-keeper and even a policemen. But the most interesting was:

Mrs Florence Sergeant (34). One of the few married women in the volume. She was sent by Ensign Pugmire of Regents Hall corps, and entered the home on 6 June 1893, giving her problems as ‘unfaithfulness of husband’ and ‘drinking… [for] many years.’ 'Having made up her mind to abandon her life of sin, went to the S.A. out to the penitents' form and then 'begged to be taken somewhere from all her companions.’ Florence had ‘never had to earn her living.’ but after separation from her husband, her father, a ‘retired banker’, had been ‘very kind’ and allowed enough money to live on. Unfortunately the right-hand page of her record is mainly blank, so we don’t know what happened to this private school-educated woman on leaving the home.

Amelia Lee (16), a true orphan, had been in domestic service before she arrived at Brent House. ‘After robbing her mistress of money and small articles for some time ran way to save being found out, after wandering for some time came to us.’ Described as ‘Short, stout, brown hair & eyes, grey.’ her conduct in the home was good, and she showed evidence of being saved. She was described as ‘quiet, kindhearted & good tempered.’ Amelia was transferred to the Clapton Square home, and left there on 20 Jan 1894 to work as a servant to a Mrs Marshall, Clapton.

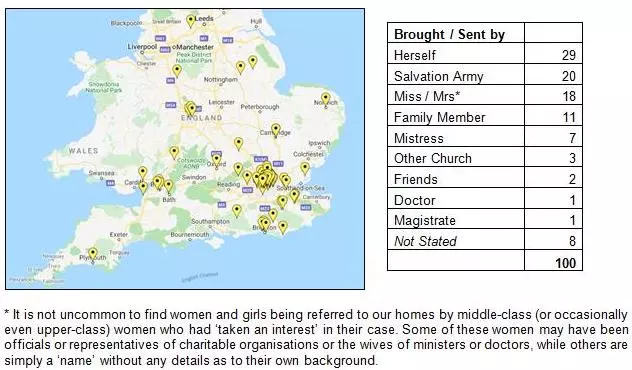

Where they came from

While many were local, some women and girls travelled long distances to the London receiving home. Among the group under study for example, two girls together ‘tramped’ from South Wales to London.

Annie Harding (17) had been a housemaid, ‘but her job was chiefly to answer the door, and as many university students called at the house, she became intimate with some of them. She left but got in with some ‘fast’ girls and went out at night. Annie was known to have behaved indecently with members of the University and was cautioned by Oxford University constables & finally imprisoned (for soliciting on the streets). The Oxford University Police had responsibility for policing within the precincts of the university until being disbanded in 2003. Annie was eventually sent home due to her bad behaviour.

Pregnancy

Francis Rout (22) was pregnant – referred by a Mrs Newman of Woolwich. Transferred to our maternity hospital, just along the road at 271 Mare Street. Didn’t stay long, as she was found to have ‘previously had a child and deserted [it]…‘she was traced [to the home] and taken up by the police,’ while still five months pregnant.

While some, like Frances, were pregnant, these only made up 20% of the group being studied. It is often supposed (probably because of examples from popular fiction) that if a young servant became pregnant, the father of the expected child was usually the master of the house or his son. The reality was that in the vast majority of cases, where the women entering our maternity homes gave details of the putative father or her seducer, he was from the same, or similar, social class to themselves. Looking at our sample of 100 women, we can identify the man responsible in 49 cases – whether or not this had resulted in a current pregnancy. In 22 cases the women had been ‘led astray’ or ‘seduced under promise of marriage’ by the man they were ‘walking out with’ or even engaged to. A further 25 identified various individuals, including fellow servants (5 cases), ‘with boys’, when as young as 12 (4), father’s workmen (2) and her own father (2).

Employment

Harriet Lane (23), a labourer’s daughter from Bristol. ‘Harriet is a quiet respectable girl, has never been fast… will do her best in service.’ Her old mistress was very anxious to have her back*, but it was thought best not to return to her old neighbourhood to avoid the bad influences that had landed her in trouble in the first place. Eight months pregnant, her baby later died but she was found a situation as general servant in Stamford Hill.

Contrary to how it sounds, ‘General Servant’ was a specific job title. Typically employed in a lower middle-class household that could only afford one servant, the general servant performed all of the chores needed to keep a household running.

Victims of circumstances beyond their control

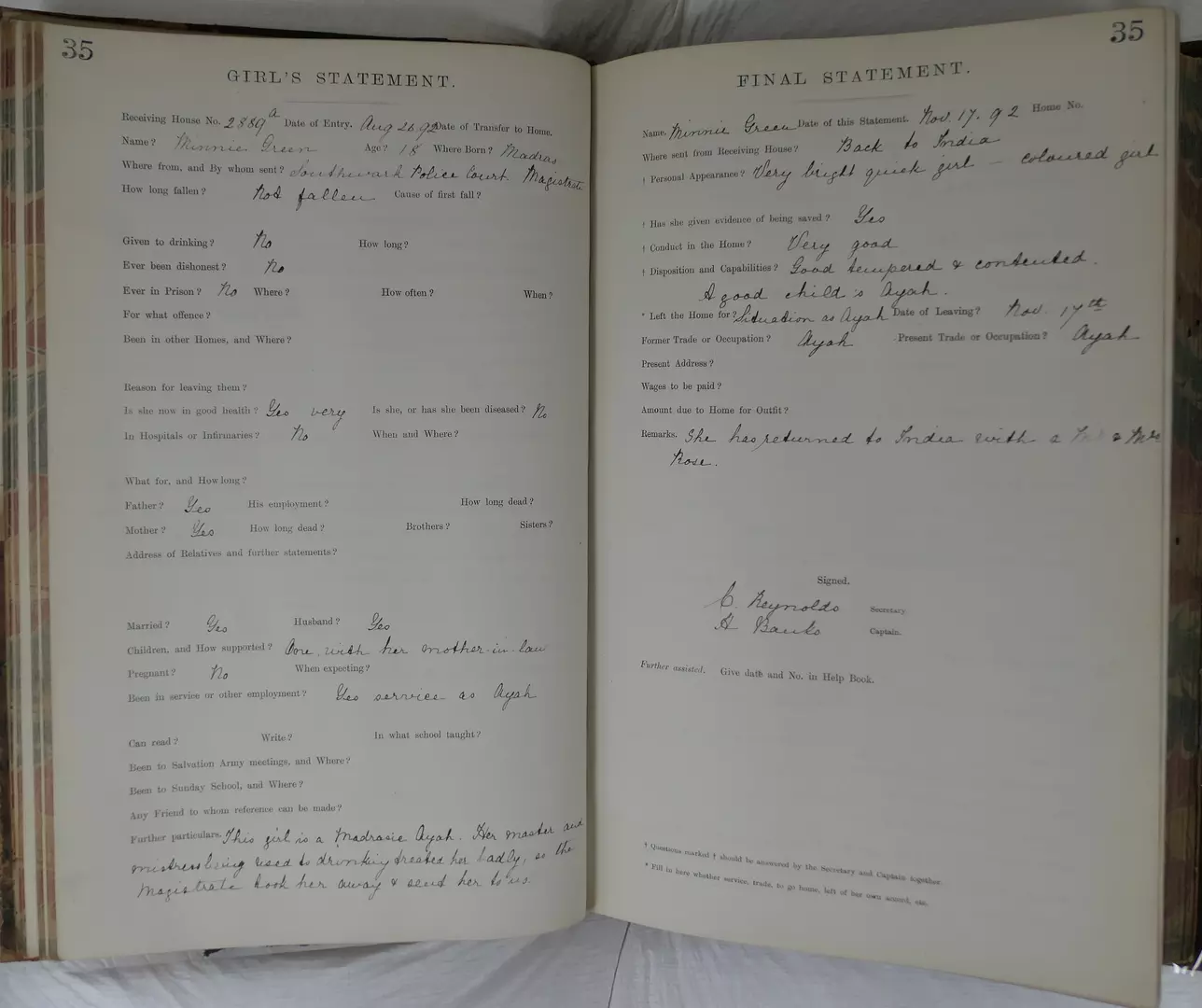

Minnie Green (18). Minnie was described as a ‘coloured girl’, an Ayah (nanny) born in Madras. Minnie had been treated badly by her master and mistress, both of whom drank heavily. As a result, ‘…the [Southwark] magistrate took her away & sent her to us.’ Her conduct in the home was described as ‘very good,’ and her disposition ‘good tempered and contented. Minnie was sent as an ayah to a Mr & Mrs Rose, who were returning to India.

Minnie would not necessarily have been out of place in the London of 1892, as there had been a home for stranded ayahs in London as early as 1825. For more information see: https://womenshistorynetwork.org/black-history-month-ayahs-at-sea/

Sarah Titmus (35) entered the home in November 1893, having been ‘Rendered unconscious in a railway carriage by a strange man.’ Ten days later she gave birth in Ivy House, our maternity hospital, just along the road at 271 Mare Street. Two months later Sarah went to stay with a sister, while baby Hilda went to a nurse-mother nearby, suggesting that Sarah was hoping to maintain contact with her baby.

There were three similar cases of women claiming to have been drugged in this volume alone, one of which the home’s officers described as ‘…very doubtful.’

Maria Roden (24) entered the home on 31 July 1893. Nine days later she was transferred to our Clapton Square home. Maria’s mother had gone away and left her with responsibility for the rent. She was so worried by this that she attempted suicide by throwing herself into the Thames. A man pulled her out & later received a 10/- reward, while she was sent first to Bethnal Green Infirmary, and, when she had recovered, to HMP Holloway. From the home, Maria was sent to Service in Hornsey for £9/year.

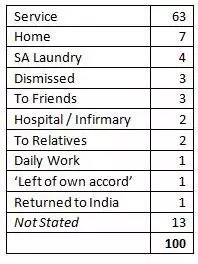

Destination on leaving the rescue home

It is worth summarising where the women went on leaving the various rescue homes.

Locations of situations

The pins in green show that most of the women who were sent to situations did so mainly in the area around the Receiving Home (shown in Red), about a 4-5 mile radius. A small number are found further west, while those in blue, clustered around Croydon and the Norwoods, are women leaving the Upper Norwood home.

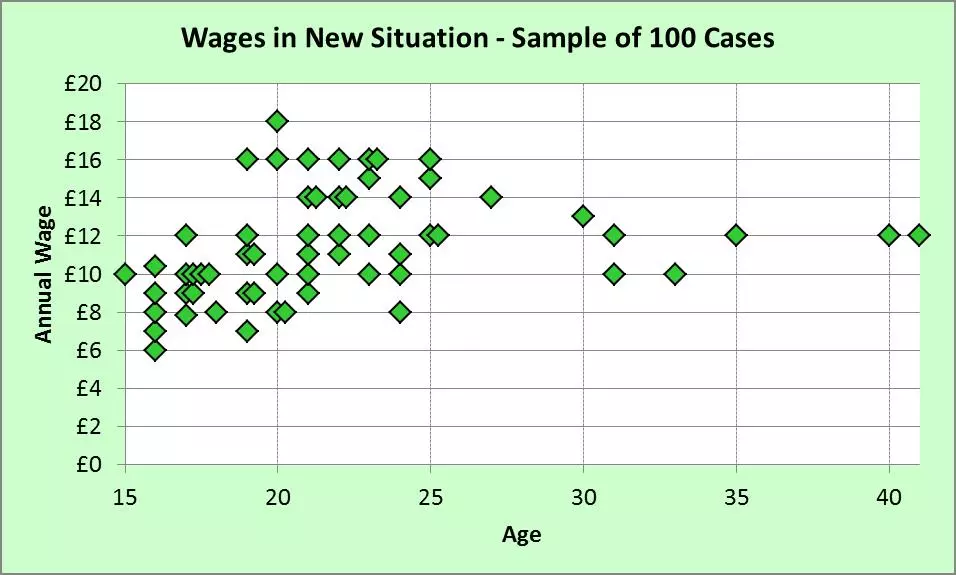

Wages paid in new position

These ranged from range £6 to £18, with a median of £11, this was about 25% less than the typical income of women arriving at the homes. Why would this be? First, the situations found for the women were almost always in domestic service, which didn’t pay as well as some of the alternatives. Looking at the highest earners on entry, most had not been in service, while some of those that had been were in more senior positions such as cooks. Also, there was the need to ‘work their way up again’, and pay tended to increase with length of time in situations.

Kevin

February 2020

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

Profitable Reading? Fiction in Nineteenth-Century Salvation Army Periodicals

From its beginnings as the Christian Mission, The Salvation Army was (and still is) a prolific publisher...

Women's History Month 2020: A Collaborative Approach

Each year Women’s History Month inspires a host of events from exhibitions and talks, to defiant marches and historic walks...

‘Inside affairs’: cataloguing the Henry Edmonds papers

Henry Edmonds first encountered The Salvation Army’s predecessor, the Christian Mission, as a teenager in Portsmouth...

‘Eat like a Christian’: Vegetarianism in The Salvation Army’s Early History

It may seem surprising that vegetarian lifestyles began to gain popular recognition as early as the nineteenth century...