International Heritage Centre blog

‘Eat like a Christian’: Vegetarianism in The Salvation Army’s Early History

‘Eat like a Christian’: Vegetarianism in The Salvation Army’s Early History

Contrary to what its title suggests, the regular column ‘What Can I Do?’ in the Darkest England Gazette rarely gave practical advice; it generally simply listed news items and facts that its pseudonymous writer considered morally good or bad.

On 24 March 1894, however, the first line of the column, as if in direct answer to the question ‘what can I do?’, stated: ‘Eat like a Christian.’ The statement is not explained and no details are given; presumably it was left up to individual readers and their religious conscience to interpret what it meant.

It is easy to see its relevance to several of The Salvation Army’s precepts such as self-denial, abstinence from alcohol, and ‘Grace before Meat’ – that is, giving thanks for a meal by making a charitable donation. A contemporary reader, however, may also have understood the recommendation as referring to vegetarianism.

While in the present day diets free from animal products are receiving increasing media coverage in the context of both environmentalism and animal welfare, it may seem surprising that vegetarian lifestyles had begun to gain popular recognition as early as the nineteenth century. Unlike teetotalism and abstinence from tobacco, a meat-free diet was never a condition for joining The Salvation Army; but from its beginnings the organisation was certainly interested in the possibility.

William and Catherine Booth, the founders of The Salvation Army, their eldest son Bramwell and his wife Florence all professed an interest in vegetarianism and seem to have adhered to a vegetarian diet at least for parts of their lives. In her thesis ‘Eden’s Diet: Christianity and Vegetarianism 1809–2009’ (PhD, University of Birmingham, 2012), Samantha Calvert shows that vegetarianism was already a preoccupation for William and Catherine at the time of their engagement, a period during which they discussed in detailed letters their ideas and values, many of which (specifically temperance) became central principles for The Salvation Army.

In 1854, Catherine asked William: ‘Have you thought any more about vegetarianism? I am inclined towards it more than ever’. It was Bramwell, however, who most publicly and consistently advocated vegetarianism. Following an address on what he called ‘The Gospel of Porridge’ at a Salvation Army conference, he published a series of articles on the subject in the Local Officer magazine in 1900; these were reprinted in the Christian vegetarian journal Herald of the Golden Age and as a pamphlet entitled ‘The Advantages of Vegetarian Diet’ by the Vegetarian Society, possibly as late as 1955.

William Booth also strongly recommended a vegetarian diet to the officers representing The Salvation Army. From 1886, his Orders and Regulations for Field Officers included a section on food, much of which was devoted to the advisability of cutting meat out of one’s diet. He explained:

"It is a great delusion to suppose that flesh meat of any kind is essential to health. Considerably more than three parts of the work of the world is done by men who never touch anything but vegetables and farinaceous [flour- or starch-based] food, and that of the simplest kind. There are far more strength-producing properties in whole-wheat flour, peas, beans, lentils, oatmeal, roots, and other vegetables of the same class, than there are in beef or mutton, poultry or fish, or animal food of any description whatever.

"The use of flesh meat may be abandoned at any time without loss in either health or strength; there may be some little inconvenience felt for the first two or three weeks, but it will be very trifling, and the benefits which follow in the way of economy, comfort, health, spirits, and ability to do mental work will be most gratifying to all who persevere with the change."

As the Orders and Regulations strictly regulated the duties, behaviour, and even appearance of officers, it is interesting that these passages are advisory rather than prescriptive. Nevertheless, the advice is forcefully given and sets out to refute any possible objections that the reader might raise. The responses to anticipated questions regarding personal health were followed by an indication of how adopting a vegetarian diet could also help the organisation to which the officer was dedicated. It states:

"In abstaining from animal food or other kinds of costly and luxurious diet, the F. O. [Field Officer] has not only the opportunity of practising self-denial, improving his health, and brightening his spirits; but he has herein the means of saving a substantial amount of money to help forward the Kingdom of God. A pound of as good and strengthening, nourishing vegetable food can be obtained for twopence as in animal food will cost a shilling. If, therefore, the F. O.’s in this, and other similar directions, deny themselves, they will save money, and set an example to others which will be certain to be followed to such an extent as will bring thousands of pounds into the Lord’s exchequer."

In other words, just as the health benefits of vegetarianism would become apparent to the officer its economic benefits would accrue to The Salvation Army as a body. A sterner interpretation was that continuing to eat meat in the face of both the personal and financial advantages of vegetarianism was an act of personal gratification not in keeping with The Salvation Army’s principle of self-denial.

The same message, albeit with less vehemence, was also conveyed to local officers and soldiers. Following Bramwell Booth’s articles the Local Officer avidly encouraged vegetarianism in the early twentieth century. In October 1903 the ‘Health Hints’ section reported ‘A Real Conversation Between Two Salvationists’ in which one asked the other: ‘I’ve often wondered what your motive was in not only being a vegetarian, but keeping it up so long!’ The response was:

"It never enters my head to alter. I now no more regard flesh as a necessary food than you regard ale as a necessary beverage. Nature’s drink is water. Nature’s food is the fruits of the earth. The nearer we can keep to these the better for our health; don’t you think so?"

This Salvationist draws a direct comparison to The Salvation Army’s stance on alcohol. No Salvationist would ever doubt the possibility of living without drinking alcohol, so the speaker points out that it is similarly feasible to live without consuming meat. In Bramwell Booth’s articles the consumption of alcohol and meat were much more closely and directly linked as he argued that ‘[o]ne bad appetite creates another’.

The ‘Health Hints’ of the December issue suggest that more Salvationists were indeed adopting a vegetarian diet, as it was directly aimed at recent converts to vegetarianism who might have doubts about their ability to achieve a meat-free Christmas. It encouraged them to resist invitations to partake of Christmas turkey, comparing the new vegetarian to a teetotaller surmounting the temptation of the increased consumption of alcohol over the holidays. It promised:

"You will be respected far more, even by those who coax you most, if you stick to your resolution, and show them all that you can go happily and merrily through the holidays and come out fresher and in better form at the end, on a diet of vegetables, fruit, nuts and pudding.

"Mince-pies can be made, with butter used instead of lard in the pastry, and chopped brazil nuts substituted for suet in the mince. Plum puddings are a great deal nicer without suet. Any sort of chopped nuts, or butter can be used. In the opinion of most children, and perhaps of some adults also, the nicest part of goose is the sage-and-onion ‘stuffing,’ and the apple-sauce, etc., which accompany it. These can be provided, and will be enjoyed with haricot-bean or sweetcorn fritters, Yorkshire pudding, lentil or pease pudding, stewed macaroni, or any of the simple, wholesome dishes which so easily take the place of meat."

Again, wider economic benefits also come into play, as the article points out that ‘[a] fruit and vegetable meal, while just as enjoyable and more nutritious and satisfying, can be managed less expensively. Thus there will be something extra to spare for His “little ones”’.

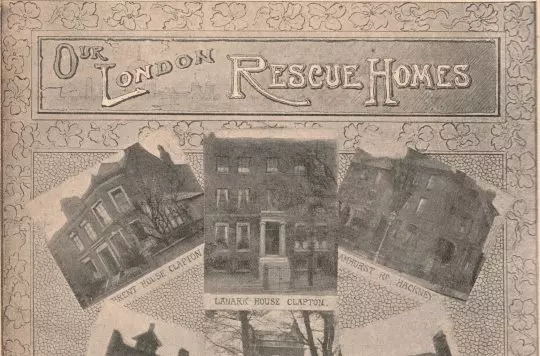

While Salvationists were thus encouraged to embrace a vegetarian diet to free up money to be donated to the work of their organisation, vegetarianism was also explored within the social work to which these funds contributed. A meat-free diet was felt to have beneficial effects on mental as well as physical health which various Salvation Army institutions were keen to harness. The young girls living in the home The Nest were served exclusively vegetarian food because it was believed to help their recovery from traumatic experiences. Meat-free diets were also used in facilities for women recovering from alcoholism with the aim of reducing the craving for alcohol. Calvert notes that the food served in hostels for homeless men was often (though certainly not exclusively and perhaps not even deliberately) meat-free, largely because it was easier to supply vegetarian food at a low cost.

While vegetarianism, then, was never officially adopted by The Salvation Army, the Booths’ early interest in it permeated the organisation’s activities, from Field Officership to the Social Work, from the late nineteenth well into the twentieth century. The concept connected with The Salvation Army’s emphasis on self-denial and temperance but also with a stance against animal cruelty which was reflected, for instance, in the Darkest England Gazette’s opposition to vivisection in the 1890s. Unlike temperance, vegetarianism was encouraged rather than imposed – the Booths themselves seem to have been inconsistent vegetarians. Salvation Army periodicals offered suggestions for vegetarian cooking and eating to make it easier to transition to a vegetarian lifestyle. While it was not necessary to foreswear meat to be a good Salvationist, therefore, it was certainly suggested that adopting a vegetarian diet was a step towards becoming a better one.

Flore

December 2019

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

A closer look at The Salvation Army's London Rescue Homes

The Girls’ Statement Book VII is one of more than 120 volumes containing details of women and girls who passed through Salvation Army rescue homes...

‘Inside affairs’: cataloguing the Henry Edmonds papers

Henry Edmonds first encountered The Salvation Army’s predecessor, the Christian Mission, as a teenager in Portsmouth...

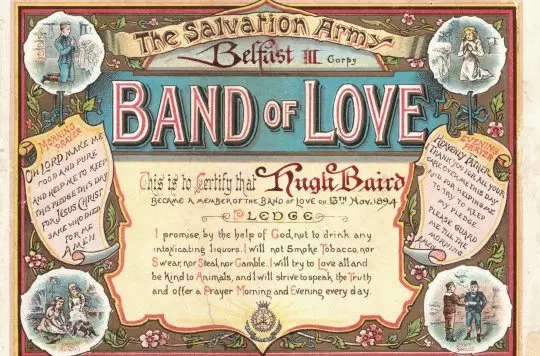

The Band of Love

The Salvation Army has been committed to temperance as part of its evangelical Christian mission since it was founded in the 1860s...

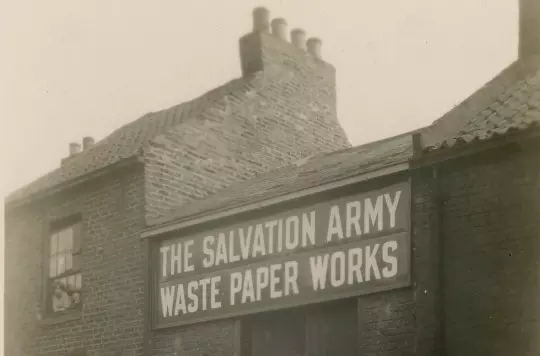

‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’: Salvation and Salvage at the Turn of the Century

The paper recycling system was a metaphor for William Booth’s vision of the spiritual transformation of Britain’s poor...