International Heritage Centre blog

'The only religious body which has always some of its members in gaol'

'The only religious body which has always some of its members in gaol'

Over Summer 2023 our Records Management team had the opportunity to review over 20 years of paperwork from The Salvation Army UK and Ireland Territorial Headquarters. Through reviews like this, the current paperwork of The Salvation Army contributes to evolving narratives of social transformation in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Within this collection my attention was drawn to one particularly large, red book. This book contains prison visitation statistics from the 1980s to 2000, and its inclusion expands our understanding of the history of the Prison Service, whose story goes back all the way to 1883.

The Prison Gate Brigade

Originating in Melbourne in 1883, the Salvation Army Prison Gate Brigade would soon spread across The Salvation Army’s international operations, including in the United Kingdom. The initial goal of the Prison Gate Brigade was to meet prisoners as they were discharged from the prison gates and offer them food and shelter at a Prison Gate Home, so long as they were willing to abide by rules and work their fair share, with no money taken from them until they earn a fair wage. An example of the message given to recently discharged prisoners can be found in the 1903 edition of Field Officer:

'Friend, we have provided a little breakfast for you this morning in our hall, Thompson’s Yard, Westgate. No charge will be made. Don’t despair! There is hope for you! Should you want advice, we are your sincere friends, and will be glad to help you. God bless you!'

Right - Mary Booth and May Whittaker at Parkhurst Prison, 1910.

At this breakfast a second message was given to the discharged prisoners inviting them to a service, as it was feared this would be rejected as a ‘preachment’ at the prison gates:

'Dear Friend, we are having a bright, brief, and brotherly service after breakfast. You are specially invited to stay. What are your future prospects? Can we help you? We shall be most happy to do so. God bless you! '

From there, for those who stayed in these Prison Gate Homes, the aim was to secure clothing and work, and often to include these reformed prisoners into Salvationist communities. By 1911 the Salvation Army prison service had spread to almost all the fifty-six countries and colonies the Salvation Army operated in. In his 1890 book 'In Darkest England and the Way Out', William Booth outlines his views of the Salvation Army prison service. For Booth, the prisons of his time failed as reforming institutions, with the lack of post-incarceration support or employment driving people into repeated patterns of criminality. He outlined the three key activities of the prison service going forward, those being the prison gate homes, the securing of suspended sentences where the Salvation Army took on the burden of care, and entry into the prison system to make early acquaintance with prisoners.

A certain quota to the prison population

The early prison work of the Salvation Army grew with the gradual approval of local authorities, however, in many ways it is remarkable that the Salvation Army was granted this authority, as during its early years Salvationists were often found to be on the wrong side of the law. A dramatic example of this was William Booth’s daughter Catherine Booth, who in 1883 was briefly arrested in Neuchâtel following attempts to spread the Salvation Army to France and Switzerland. In prison she wrote penned the following poem:

'All my life is at thy service, all my joy to share thy cross, I am thine to do, or suffer, all things else I count but loss.'

Her chief of staff and future husband, Arthur Clibborn, penned his own prison poem:

'Thy love condescended – t’was loves great saving plan, to take human nature, become a son of man. But o! t’was to raise me a son of God to be, no rest has thy love till I am like to thee.'

The Booth-Clibborn case would draw attention from leading campaigners in England, with connections to prominent figures of the time such as prime minister William Gladstone, newspaper editor William T. Stead, and social purity campaigner Josephine Butler. However, many Salvationists would face imprisonment without this profile, taking to the streets in acts of civil disobedience. In 1888 Salvationists protested the Torquay Harbour Act for prohibiting musical processions, leading to the arrest of twenty-four with sentences ranging from seven days to one month, including repeat sentences as those initially incarcerated returned to protest upon their release. Eventually the Salvationists succeeded in repealing this new law, which Captain John Roberts compared to Daniel 3:16-18:

'Oh Local Board, we are not careful to answer thee in this matter, our God whom we serve is able to deliver us out of the cells of Exeter Prison and He will deliver us out of thine hand, oh Local Board, but if not, be it known unto thee, oh Local Board, we will not obey thy coercive command, nor pay attention to the 38th section which thou hast inserted in the Torquay Harbour Act'

Salvationists, and those working with the Salvation Army, have throughout history risked incarceration, be it for national causes such as the 1885 campaign in the United Kingdom to raise the age of consent, for local causes such as the right to procession, as a consequence of operating in theatres of conflict such as in WW2 Europe and Asia, or for ideological reasons as in 1950s Communist Czechoslovakia. To William Booth, this was seen as an asset, as he writes within 'In Darkest England and the Way Out' as follows:

'I believe I am in the proud position of being at the head of the only religious body which has always some of its members in gaol for conscience’s sake…

No great cause has ever achieved a triumph before it has furnished a certain quota to the prison population…

When a man has been to prison in the best of causes he learns to look at the question of prison discipline with a much more sympathetic eye for those who are sent there, even for the worst offences, than judges and legislators who only look at the prison from the outside.'

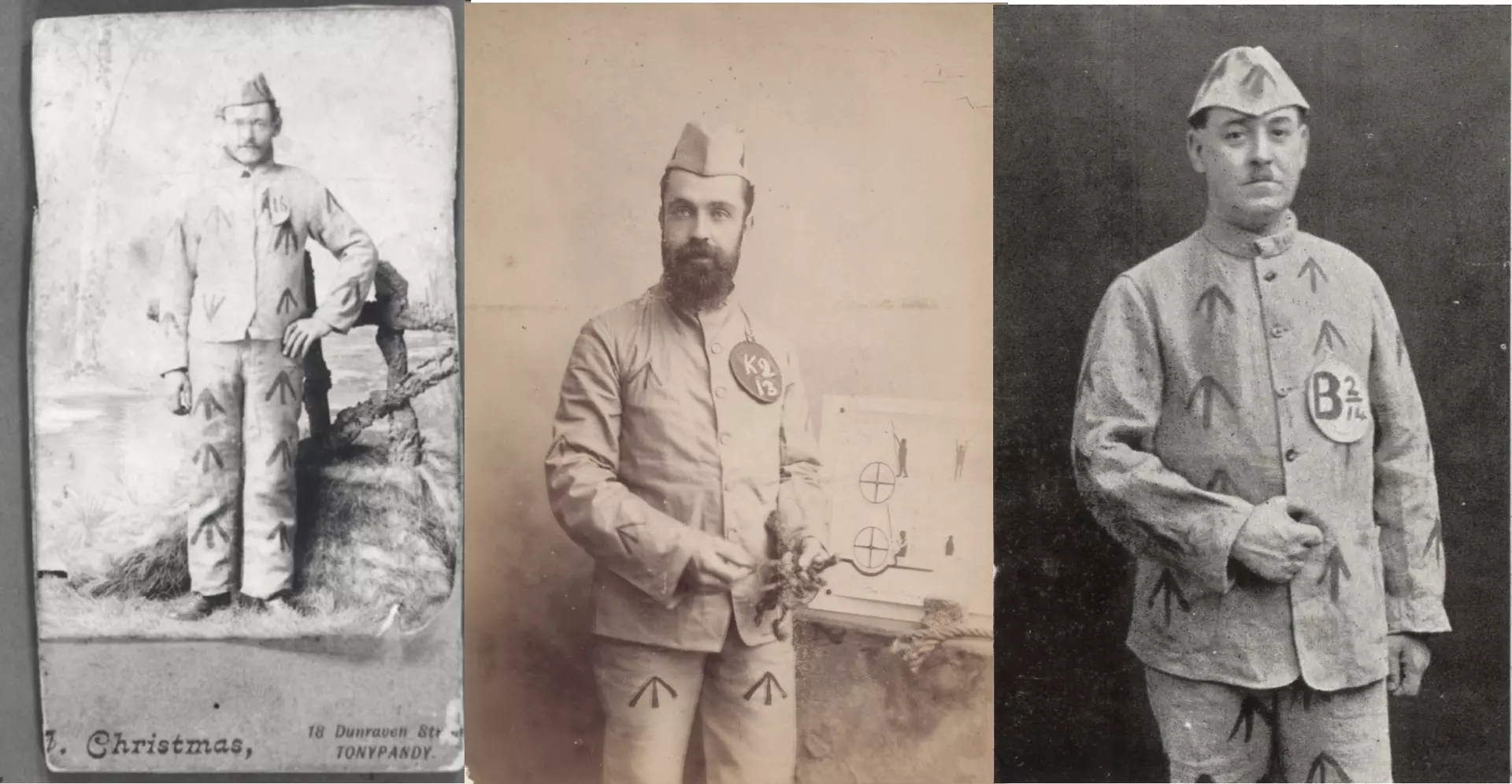

Right - Salvationists Myra Davis and Mary Fairhurst after release from Derby Jail, 1887.

Centre - Salvationist Charles James Gardner, 1892.

Right - Salvationist W.A. Waters, approximately 1900.

A power for good wherever he moves

For William Booth and the Salvationists, there was a clear difference between being imprisoned for your convictions and being imprisoned for criminal behaviour, and these early campaigners would stress the importance of lawfulness. Despite this difference, it was recognised that former prisoners had a place within the Salvation Army, and their experiences offer unique insights for the prison ministry services. For many former prisoners the prison service was solely intended to serve as a steppingstone to a better life, but some testimonies of former prisoners undergoing a complete damascene conversion into Salvation Army service have emerged over the years. One former prisoner from Jamaica, named only as Simonson, is accounted as such in 1925:

'His profession being followed by an immediate change of life left little room for doubt regarding his sincerity, and since then he has adequately manifested the genuineness of the change. Working regularly in the city, he now attends Salvation Army Meetings, his evident delight in which it is pleasing to notice. Enthusiastic in testimony and earnest in prayer, he is a power for good wherever he moves, and he is already a well-known and uniformed Salvationist.'

A further account from Brigadier Heinrich Tebbe comes from 1927 Germany:

'One was visited by us for years. He had been often convicted and had even escaped from prison. He has now been free for three years; He found refuge in the Lord and was enrolled at one of our Corps. Happily married a year ago, he is himself appointed Welfare Sergeant for prisoners, and works well, out of thankfulness for having been saved.'

These accounts give compelling testimony to the value the Salvation Army placed on the experiences of former prisoners as outlined by William Booth. However, access to early statistics on the prison service is limited and tends not to record the number of soldiers drawn from the prisons. For instance, the Darkest England Scheme, started in 1890, had by 1920 recorded the cumulative work from the prison service.

'Number of Ex-Criminals received into homes – 12,352.

Number of Ex-Criminals assisted, restored to friends, sent to situations, etc. – 15,288.'

Later intervals of prison service statistics can be found in the Salvation Army annual reviews, which offer limited insights, such as this section from the 1938 review.

'4,989 prisoners were helped on discharge from prison or police court, and our Officers had 13,149 personal interviews with prisoners in their cells.'

For comparison, this is stated in the 1961 review.

'Correctional Services Department Officers continue to minister regularly in penal establishments throughout the British Isles, visiting 11,397 men and assisting relatives as special problems arise.'

Soldiers Made

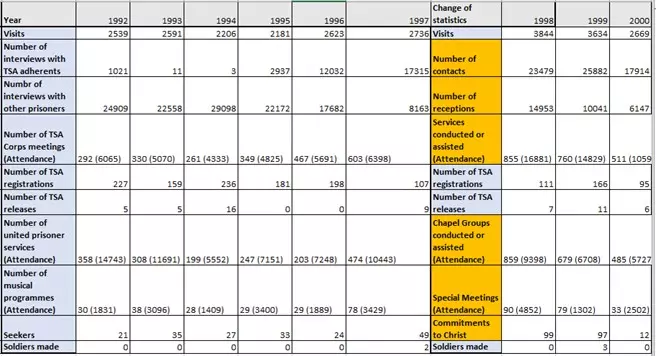

Returning to our big red book of statistics, we can see how the original values of the Salvation Army prison service translate to the methods and challenges of the service in more recent history today. This book gives comprehensive account of the prison visitation statistics in England and Wales from 1980 to 2000, though the years 1986, 1987, 1989, and 1990 are currently missing.

These statistics can trace broad trends in the activities of the Salvation Army prison service, which appear to have consistently increased during this period. Though the statistics themselves don’t offer an explicit explanation of why service has increased, there is a potential explanation within this book, where an attached report states as follows:

'In 1993 the total prison population in the UK was about 52,100 or 90 prisoners per 100,000. The total prison population in England and Wales in 1991 was 45,873 compared with 47,746 on March 31, 1992, a rise of 1,873. Nine prisons were 50% or more overcrowded on March 31, 1991, compared with eleven on March 31, 1992.'

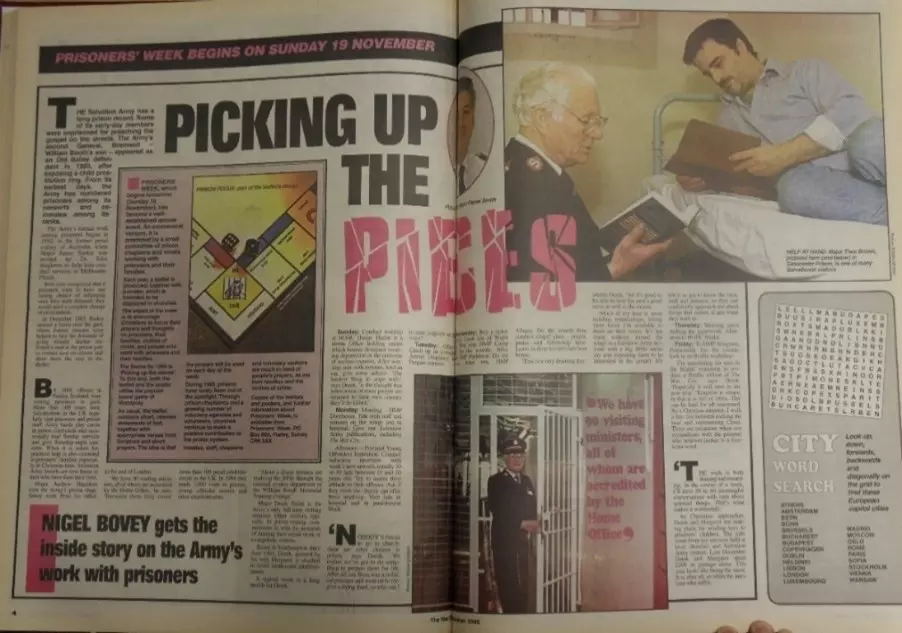

The types of statistics recorded also tell us a lot about the work of Salvation Army prison ministers, and how that has changed over time. According to the 1952 Prison Act, which remains the legislative foundation for prisons in the UK, the prison chaplain is to belong to the Church of England, though visiting ministers can be appointed from other Christian denominations. Over time, this has been reinterpreted to create today’s multi-faith prison chaplaincy service. Amongst the key duties of the visiting ministers, later solidified in the 1999 Prison Rules, were interviewing each prisoner, visiting prisoners in sick wards and punishment wards, and responding to all applications for service. These applications varied in nature, and often involved enquiries into prisoners’ relatives.

The United Prisoner Services referred to up until 1997 were conducted across denominations. These provided the Salvation Army the opportunity to register prisoners as Salvation Army adherents. From there it was recorded when an adherent becomes a seeker through a commitment, and where a prisoner adopted the life of a soldier of the Salvation Army. From these statistics we can see that the direct conversion from prisoner to soldier of the Salvation Army is a rare and deeply personal journey, likely accounting for the absence of this figure in earlier statistical reviews, though its continued presence speaks to the value place on former prisoners. Furthermore, though this number of soldiers made from within the prisons was low, not all former prisoners in the Salvation Army joined immediately from incarceration. Accounts of the value ex-prisoners bring to the Salvation Army and the prison service can be found throughout recent issues of Salvationist, such as the accounts of Temo Galustian, Darren Wooldridge, Jonathan Aitken, and Edward Smyth.

Free access to prisons and public institutions

Over time, the prison service changed, and the Prison Gate Brigade was discontinued in the United Kingdom. The last mention of the ‘Prison Gate and Prisoners’ Aid Department’ in the UK year books comes in 1910, simplified in the following 1913 issue to the ‘Prisoners’ Aid Department’. Despite this, mentions of prison gate work can be found in annual report expenditure summaries throughout the 1930s. Though the term remained relevant, the Salvation Army would transition in this period from an organisation whose members were regularly incarcerated within prison cells, into an organisation trusted and collaborated with by governments across the world. Shortly before his death, Commissioner George Scott Railton outlined this desire for change in the 1913 annual review.

'In almost all Colonial Prisons and those of the United States, Japan, and Korea, we have liberty both to visit prisoners in their cells, and to hold Meetings with them at duly specified times. Even in the United Kingdom some of our Social Officers have a good deal of this liberty, and are heartily welcomed by most chaplains, it having been abundantly shown that we cause no religious controversies, and keep clear of all political or social broils.

What a natural thing it would be, by way of recognition of the work of General Booth, for his Successor, and such Officers as he might appoint for the purpose, to be allowed as free access to prisons and public institutions of every kind, including barracks, warships, and workhouses, as any other religious teachers! Why not?'

Though prisoners are no longer met outside the prison gates, work starts inside of the prison today, and for new adherents a community exists outside of the prison walls prepared to host them as the Prison Gate Brigade once did. Other tasks such as securing employment opportunities have been adopted by new departments of the Salvation Army, and Salvation Army releases are secured to this day. Whilst changes in legislation, prison standards, and the relationship between the Salvation Army and authorities have necessitated adaptation from the prison service, the present service can trace a clear lineage to those pioneering Salvationists who stood outside the prison gates.

Thomas

August 2024

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

Marie Booth: the forgotten Booth daughter

Birkbeck intern Laura did some digging in the archives to find out more about William and Catherine’s sixth child.

Love Across the Sea

Take a look at some of the letters Brigadier Frederick Cox wrote to his wife while he travelled the world with William Booth.

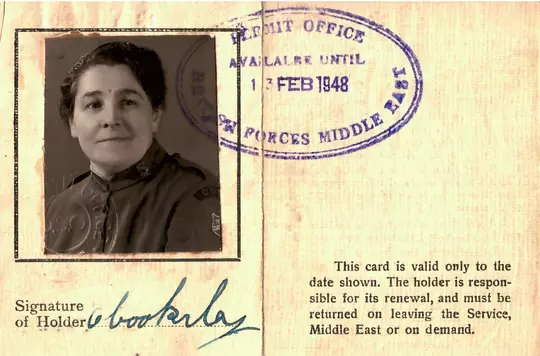

Women’s History Month 2023: Salvation Army Women in Egypt.

Catch-up on this years' Women's History Month exhibition with this blog post about Salvation Army women in Egypt.

‘Evangelical Thrust’: The Salvation Army in the New Towns

In the 20th century the landscape of Britain's towns and cities began to change and the architecture of Salvation Army halls changed with them.