International Heritage Centre blog

Love Across the Sea

‘I think that the least I can do is to do the best I can for those I love more than all else on earth beside’

In July 1858, Frederick Richard Cox was born in Kentish Town, London. His father was a man of business, his mother devoted herself to raising Frederick and his three elder sisters. At 15, he left home to become a sailor, and for 12 years he travelled the world by sea. In 1884, whilst travelling in Melbourne, Australia, Cox attended a Salvation Army meeting, where he decided to give his life to God.

Two years later in June 1886, Cox was working aboard a ship called the Iole which broke into pieces on the banks of the Humber. The shipwrecked crew were cared for at the Salvation Army corps in Hull. It was here he became captivated by a 19-year-old Officer called Amy Biddington. According to He was There, the 1949 biography of Cox produced by his son F. Hayter Cox, Cox decided to become an officer in order to be able to marry Lieutenant Biddington. After completing his training, Fred and Amy were finally married in 1888. In the weeks before their wedding, Frederick wrote to Amy ‘Oh darling, won’t it be heaven! No more good-byes-no more farewells-but one long lasting enjoyment of another’. After their marriage, Amy wrote to her sister ‘For me it seems as if I had entered into a heaven below’

They did not know that ahead of them was a future of separation, longing and loneliness.

The Frederick Cox family papers which have now been catalogued, contain a wealth of correspondence and material which give us an insight into the earliest years of the Salvation Army. They also document a beautiful love story between Frederick and Amy, which ran alongside their work and commitment to the movement.

In 1893, Cox joined the personal staff of William Booth and was appointed his Private Secretary in 1901. In this capacity he accompanied Booth on a series of lengthy and demanding international tours to North America, mainland Europe, the Middle East, Australia, New Zealand and Japan from 1902-1907. From these locations, he wrote home to his much-cherished Amy. This proves to be one of the unique features of this collection; the letters provide a level of intimate detail about these tours and an insight into his feelings during this challenging time.

In October 1902, Frederick writes to Amy ‘his darling sunshine’ from a ‘vessel on the Atlantic’ explaining he has devised a ‘code’ which he will send to her. The code gives disguised names to senior Salvation Army Officers and places, so they can talk secretly together. These code words are used in following letters, showing a private world that only Frederick and Amy can access.

Not long after this, Amy sends a heart-breaking telegram to Fred ‘Olive. Convulsions. Gone. Come Home’ Their second child, just a baby, has died, but it is a little while before Frederick can return home.

By Christmas 1902, the depth of how much Fred misses Amy in shown in his letter home ‘Perhaps you might be disposed to say that distance lends enchantment to the view, but I say that Home sweet home is sweeter far now than ever…’ In April 1903, he writes ‘My heart is longing for you even as I write. I have been taking a big dose of tonic and kissing your pretty little photo again and again. I have it laid down by my side as I write this and am finking about you and loving you.’

On the Australian tour in 1905, Frederick Cox becomes ill with Dengue fever, and sounds increasingly downcast and depressed in his letters. However, he states to Amy that ‘I said I would not leave the General if I died at his feet, and I went on.’

Although, the majority of the collection reflects Fred’s Salvation Army career, it also contains some fascinating insights into Amy’s work as she remained behind in Wood Green, North London. She maintained a relationship with Emma Booth and Florence E. Booth and appears to have offered accommodation in her own home to women received by various branches of the Women’s Social Work. The most intriguing reference to this points to a collaboration between The Salvation Army and famous investigative journalist W. T. Stead in 1892, seven years after the notorious ‘Maiden Tribute’ case of 1885. Notes exchanged between the Coxes, Florence Booth, and W. T. Stead suggest that Stead’s reporting involved a woman who was staying with Amy Cox.

In May 1907, Frederick Cox writes excitedly from Tokyo, as he is soon to come home ‘I am bringing home for you a trunk, all for your own little self, and I want to have a sort of little ceremony… handing you the key and making a little speech… Good night beloved.. what a comfort it is to be sure you really love me. I do need some love I do, I am wretched and miserable and lonely and almost starved’

The relief is clear in his writing. Although he believes wholeheartedly in the work, he knows he has sacrificed much during these years of touring the world. The conditions at sea, the rapidly declining health of William Booth and the challenges faced in each country have been exhausting. At last, he can come home to his beloved Amy.

In January 1927, Amy Cox was promoted to glory. Frederick only lived another 14 months without her.

Naomi

May 2023

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

'The only religious body which has always some of its members in gaol'

Find out about the history of The Salvation Army's prison service, which goes back to 1883...

Marie Booth: the forgotten Booth daughter

Birkbeck intern Laura did some digging in the archives to find out more about William and Catherine’s sixth child.

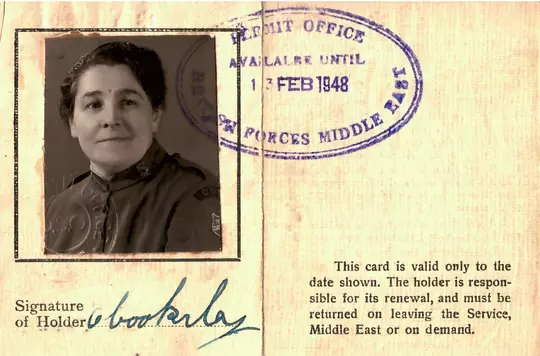

Women’s History Month 2023: Salvation Army Women in Egypt.

Catch-up on this years' Women's History Month exhibition with this blog post about Salvation Army women in Egypt.

‘Evangelical Thrust’: The Salvation Army in the New Towns

In the 20th century the landscape of Britain's towns and cities began to change and the architecture of Salvation Army halls changed with them.