International Heritage Centre blog

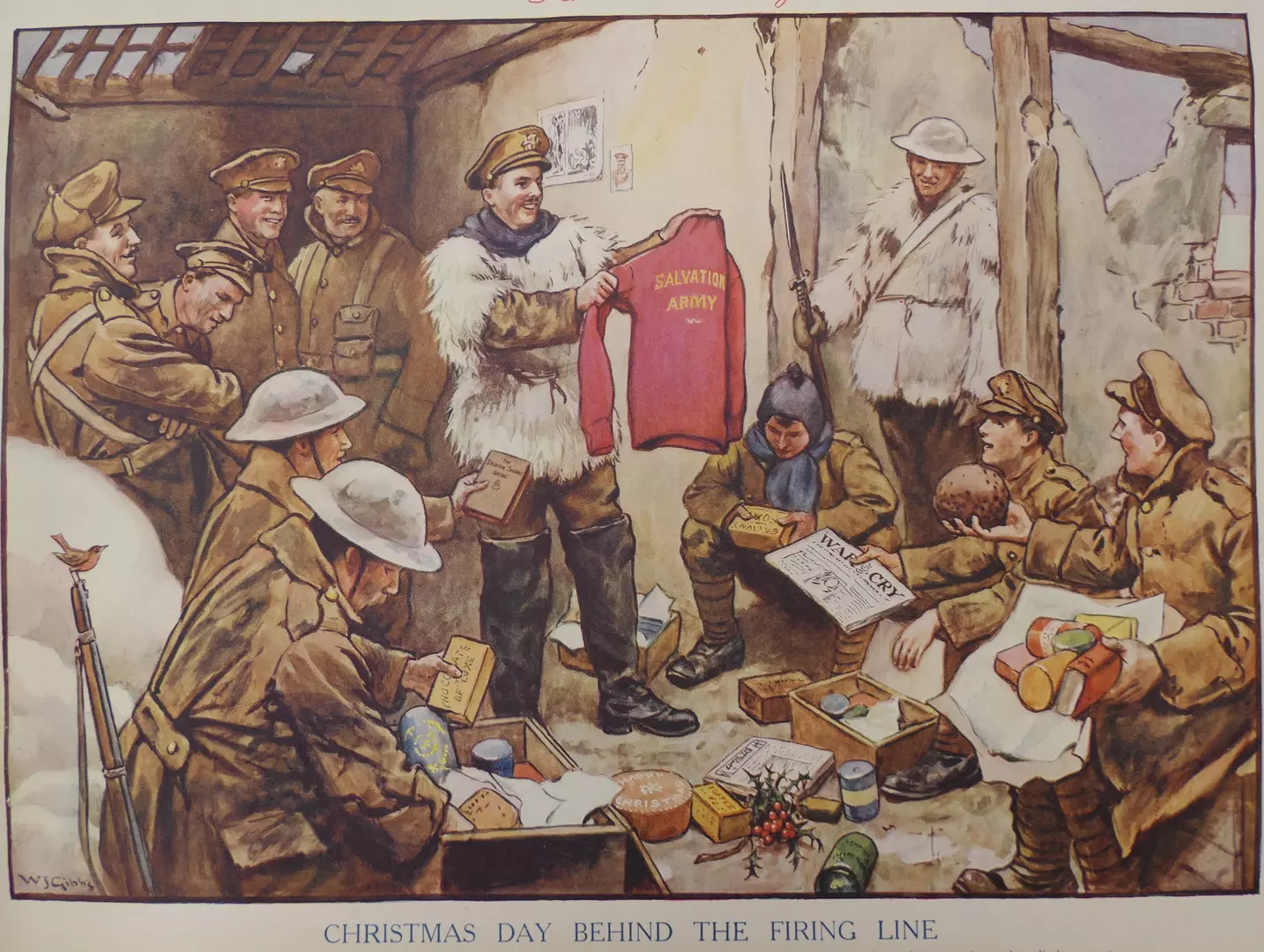

‘A New Kind of Help’: Comforts in the First World War

‘A New Kind of Help’: The Salvation Army and comforts in the First World War

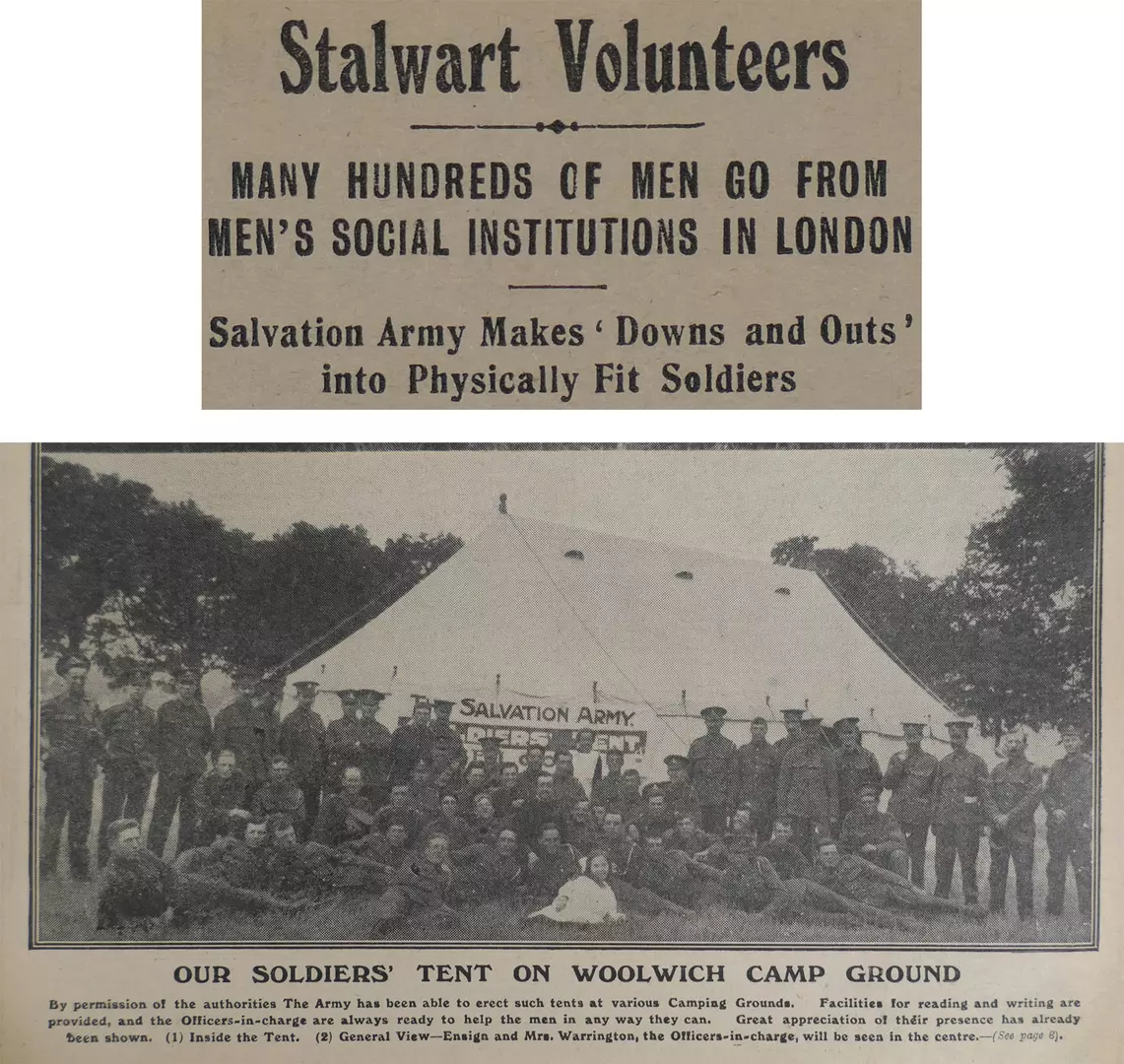

By the outbreak of the First World War, The Salvation Army in the UK was well-established in a range of fields of charitable work. Up to this time its welfare work had largely been shaped by the needs of the urban poor, resulting in the provision of labour exchanges, night shelters, hostels, food depots and maternity services, as well as industrial homes and elevators which both provided housing and work to the unemployed. However, virtually overnight, the war changed the landscape of British society and with it the needs that charities like The Salvation Army existed to meet. Many of The Salvation Army’s hostels and elevators for men emptied as residents enlisted or were called up to fight, but this created new spheres of work as The Salvation Army stepped in to provide support services among the troops.

Meanwhile the need for women’s and children’s welfare services remained high as it took time for financial support from the government to reach the families of enlisted soldiers. Female unemployment also rose sharply in the early months of the war as industries which had previously employed women closed or were scaled back.

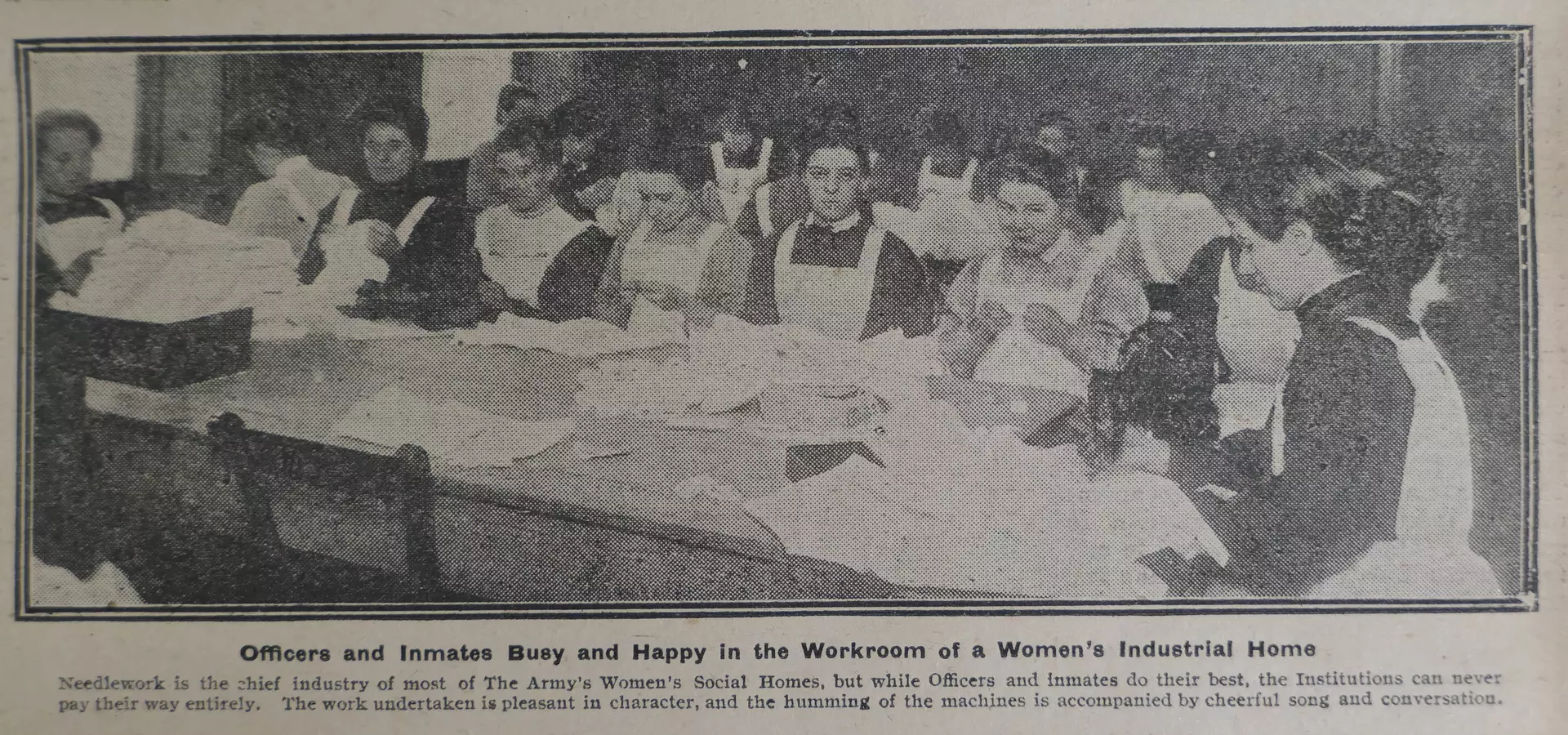

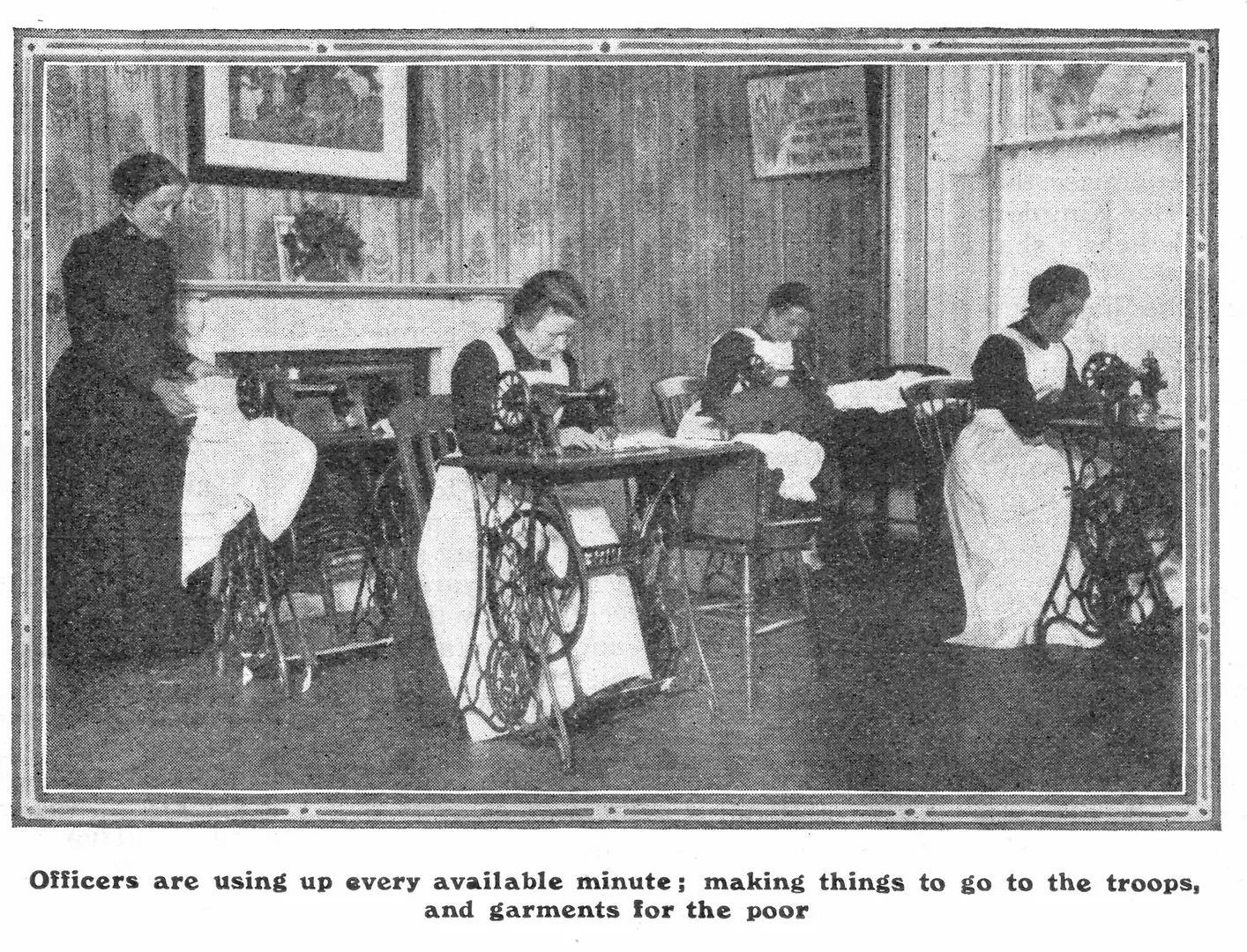

One industry from which many women lost jobs was textile and garment manufacturing. The war closed off export markets on which this industry relied. Perhaps surprisingly, The Salvation Army had a small stake the textile industry at the time through its women’s industrial homes. In most of these industrial homes, female residents undertook needlework, producing sewn garments and embroidery.

There was also one knitting home which provided a small number of women and teenage girls with residential employment training using industrial knitting machines (school leaving age at the time was 12). These industrial homes were run on charitable rather than commercial lines: the women and girls were not paid a wage for their labour but were provided with fully catered accommodation for the duration of their training. The proceeds from the sale of their products were treated as contributions towards their maintenance, with any excess going towards The Salvation Army’s charitable work more widely. Some of the textile products from the homes were sold by mail order to Salvation Army members and supporters worldwide, but the majority were sold by means of a dedicated network of pedlars, or ‘Sales Officers’, who operated throughout the UK.

The wartime conditions very quickly began to affect the work of these and other Salvation Army homes for women, as the organisation’s Women’s Social Work magazine, The Deliverer, reported in September 1914:

"Friends will understand that, owing to the general distress, every household is, I suppose, attempting to reduce expenditure, therefore our dear Officers who sell the goods which provide the necessities of life for our poor people in and outside our different Institutions, do not find as ready a sale as usual for the articles which they offer."

The pedlars’ difficulties meant that, at a time when increasing numbers of women faced hardship, the wing of The Salvation Army which existed to help women in need found itself with an ‘empty exchequer’.

When, in August 1914, Queen Mary appealed to needlework guilds throughout the UK to make and collect garments for distribution amongst the troops and others who would suffer on account of the war, members of The Salvation Army’s women’s association, the Home League, busily set to work with their needles. However, Commissioner Adelaide Cox, the leader of the Women’s Social Work, also saw an opportunity. She wrote to supporters in The Deliverer:

"It has occurred to me that some who would very gladly help in this direction may be unable to find the necessary time to make the different garments. This gives me an opportunity to put in a plea for our needlework rooms. […] I therefore suggest—could you not place your orders for these things, or some of them, with us?"

In an effort to reach a wider audience, the same appeal from Commissioner Cox also appeared in The War Cry, but the editor of The War Cry introduced another perspective on the matter:

"The Women’s Homes are begging for orders to keep their work rooms busy. Voluntary labour is all very necessary no doubt, but to give an order for the needlework needed, whether for the soldiers, the wounded, or to meet one’s ordinary needs is better still."

This reservation about voluntary labour was shared beyond The Salvation Army. There was unease in various quarters about Queen Mary’s call for voluntary garment making when so many garment workers were out of work. The Queen’s appeal was prominently opposed by the War Emergency Workers’ National Committee and the East London Federation of Suffragettes, the latter issuing a counter appeal (in starker terms than The War Cry) ‘to leisured people not to start sewing for the soldiers and others whilst women who hitherto have earned their bread by such tasks are left to starve.’ The War Cry also reported that a donation of fabric had been received from an anonymous donor on condition that the work of turning it into garments for soldiers be ‘given to poor women who have been thrown out of employment owing to the war’. The newspaper advocated each week for the continuing importance of The Salvation Army’s social institutions in providing ‘work for the workless’.

The Queen heard these concerns and met with representatives of working women. Soon after, she inaugurated another initiative, her Work for Women Fund, to create employment for women who had lost their jobs as a result of the war. The Fund was used to award contracts to supply clothing for the Armed Forces and others affected by the wartime circumstances. Interestingly, in the next month’s Deliverer, Commissioner Cox begins her ‘Personal Notes’ with an announcement:

"I have received from Her Gracious Majesty Queen Mary an order for useful things suitable for women and children, which she desires should be made for her in our workrooms. In the message which I received from Buckingham Palace Her Majesty expresses sympathy with the effort being put forth to keep women employed."

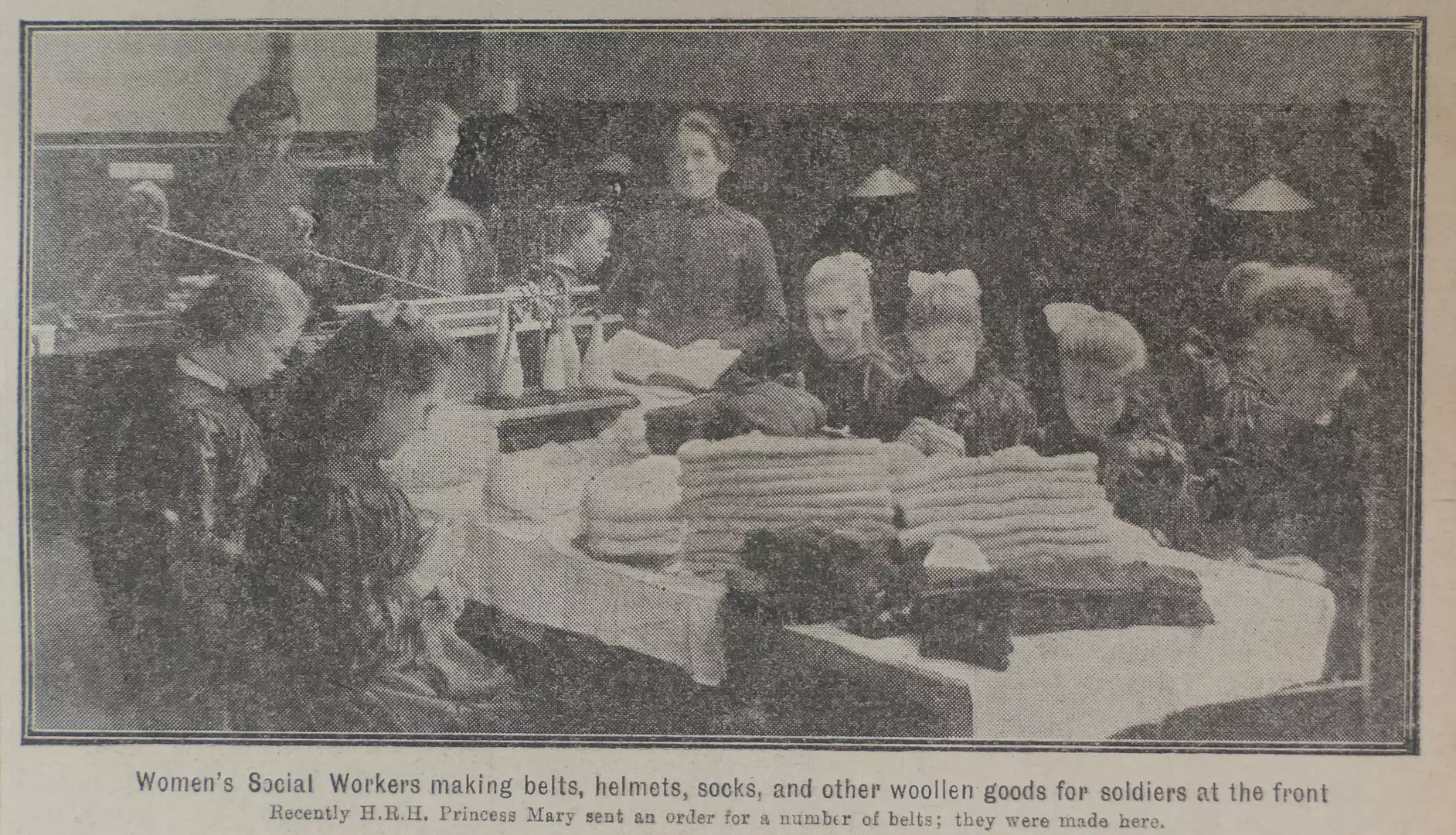

By November another order had been received:

"HRH Princess Mary sent us an order yesterday for a quantity of knitted belts, which she is sending to the soldiers. She carefully examined the samples (made to regulation sizes and shapes) which we forwarded to her, made her selection, and a message soon came through the telephone from Buckingham Palace. The knitting machines are being turned by willing hands, and the belts are emerging from them while I am dictating these Notes to my shorthand."

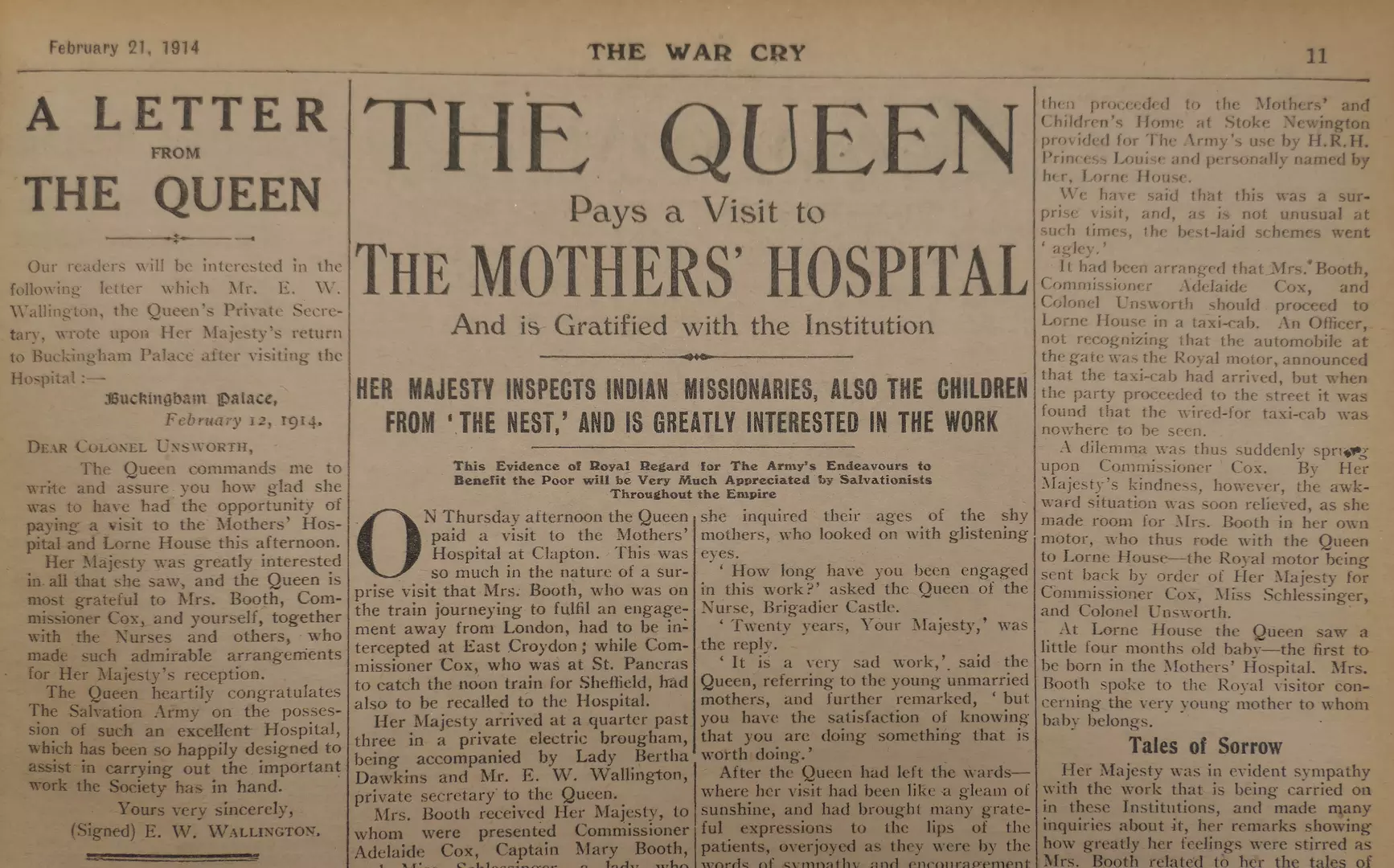

It is not apparent whether these royal orders were made from the Work for Women Fund or placed personally by the Queen and her daughter. The latter is possible given that the Queen was known to be sympathetic to The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Work. She had shown her support earlier in the year by arranging a surprise visit to the Mothers’ Hospital, which had recently been opened by her sister-in-law Princess Louise in Clapton.

By early 1915, The Salvation Army had also been entrusted as one of the charities responsible for distributing the clothing gathered under the Queen’s schemes to British troops. In January, The War Cry announced the receipt of a quantity of clothing from Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild comprising ‘60 shirts, 200 pairs of socks, and 200 pairs of mittens’. This meant that Mrs Commissioner Catherine Higgins, the head of the Home League, was able ‘to send six sacks of warm garments to France that week instead of the customary three’. Even without the generosity of the Queen’s Needlework Guild, the Home League was already producing hundreds of garments each week. In November 1914, when The Salvation Army’s first unit of motor ambulances was dedicated for service at the front, it had departed London ‘laden’ with ‘162 shirts, 320 pairs socks, as well as helmets, night shirts, gloves, cuffs, mittens, body belts, mufflers, sleeping socks, and various other garments.’ Adjutant Lucy Lee and Ensign May Whittaker, who were among The Salvation Army officers working behind the front lines in France, both testified to the enormous gratitude of those who received the comforts.

In the midst of these new demands created by the war, The Salvation Army never lost sight of its evangelistic ministry and comforts were no exception. In April 1915, Commissioner Cox reported that ‘the industry of our workrooms has even been used to send messages on some of the garments which have been manufactured there, and when they have been distributed amongst the soldiers the comfort of the garments has been enhanced by the words on them bidding the wearers to look up to our Lord and Master for His help.’ Ensign Whittaker added ‘That little motto, “Seek ye the Lord while He may be found,” has done more than one can imagine; I wish it could be put on every garment, socks, mufflers, etc., everything we have.’ Commissioner Cox wrote that she was hoping to raise funds to send garments bearing a French text which could be distributed to French-speaking soldiers too.

However, after this, no further mention of garments being made for troops in the workrooms of Salvation Army industrial homes has been found. It’s not clear exactly what brought about this sudden change, but it was possibly linked to the fact that by 1915 women’s employment was again on the rise. Female workers were in demand to fill new roles in munitions production as well as existing roles vacated by men who had enlisted or, from 1916, been conscripted. Whatever the reason, Commissioner Cox’s calls for work orders for the industrial homes ceased in 1915 as The War Cry gave increasing prominence to Mrs Commissioner Higgins’ collection and distribution of comforts that had been made voluntarily by members of the Home League and other Salvationists, friends and supporters.

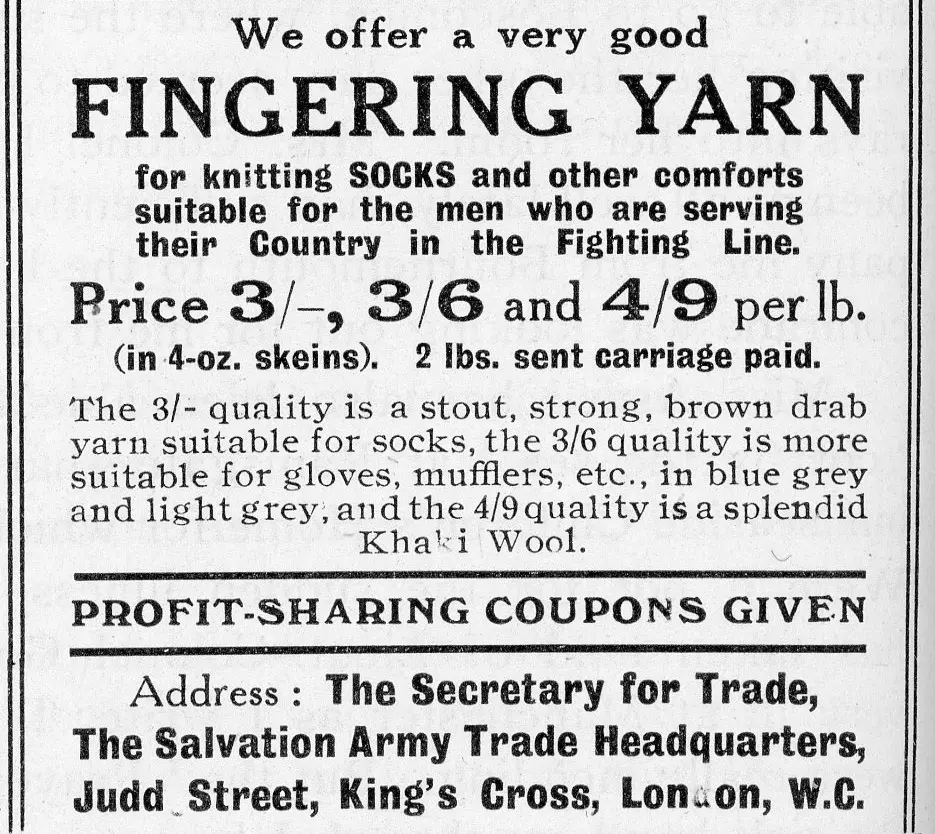

At the end of May 1915, it was announced that 10,000 garments had been received from the Home League for distribution among the troops, and another gift from Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild had also been received. Also in May, The Deliverer for the first time carried an advert from The Salvation Army Trade Headquarters for ‘very good fingering yarn for knitting socks and other comforts suitable for the men who are serving their Country in the fighting line.’ Although the tide had turned firmly towards voluntary comfort making, The Salvation Army did not lose sight of the continuing need to raise funds for its charitable work and sought to do so by selling the necessary materials for making comforts. At this time, the Trade Department also operated a profit-sharing scheme, akin to a co-op, which paid dividends annually to its customers, meaning the benefits of sales of yarn would have been felt even more widely among The Army’s friends and supporters too.

Despite the incredible effort of the Home League and other voluntary makers, The Salvation Army struggled to keep up with the demand created by the war as it continued beyond its first year. Mrs Commissioner Higgins regularly made appeals for more garments in The War Cry, warning that her cupboards were often left bare as, by 1916, she was dispatching as many as fifty parcels a week. The comforts needed changed with the seasons: during the first winter of the war, there were very moving calls for large thick socks to cover the bandaged feet of frostbitten soldiers, but by summer there was an ‘urgent need for more thin socks and shirts’. Helmets, mittens, mufflers, cuffs, gloves and underclothing were among other items called for in the course of the war. At times the results were apparently quite comical, as one officer reported having received ‘wiry socks, prickly socks, odd socks, striped socks, zebra socks, long socks (2ft. in length) … socks without heels… socks of all the colours of the rainbow’ to hand out, but this officer nonetheless acknowledged that ‘each sock [told] its own tale of love and patience’, which was in part what the recipients appreciated about them. To spur on the providers of comforts, extracts from the letters of thanks received from soldiers began to be printed regularly in The War Cry, and it is with the words of one of these grateful recipients that I’ll finish.

"Those socks you sent me came at the very moment when most needed. For days, and sometimes at nights, I have been on duty, standing for hours in water several feet deep. I truly believe there was only one thread of my old socks left when I found yours waiting for me, and I thanked God for the kind and thoughtful friends who had sent them."

Ruth

January 2023

Related reading and viewing:

Carol Harris, ‘1914-1918: How charities helped to win WW1’, Third Sector, https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/1914-1918-charities-helped-win-ww1/volunteering/article/1299786

Cheltenham Museum, ‘First World War: The Home Front, knitting’, https://www.cheltenhammuseum.org.uk/collection/cheltenham-remembers-the-home-front-knitting/

Imperial War Museum, ‘How to help Tommy’ (film), https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060031195, ‘12 Things You Didn't Know About Women In The First World War’, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/12-things-you-didnt-know-about-women-in-the-first-world-war, and ‘Nine Women Reveal The Dangers Of Working In A Munitions Factory’, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/9-women-reveal-the-dangers-of-working-in-a-first-world-war-munitions-factory

Sarah Jackson, ‘East End Suffragettes in the First World War’, The History Press, https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/east-end-suffragettes-in-the-first-world-war/

Lynda Mugglestone, ‘The comforts of war’, Words in Wartime, https://wordsinwartime.wordpress.com/2014/11/02/the-comforts-of-war/

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

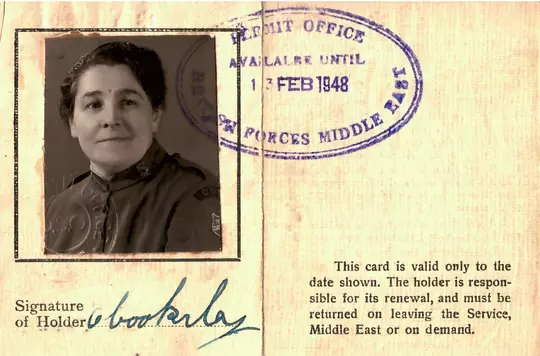

Women’s History Month 2023: Salvation Army Women in Egypt.

Catch-up on this years' Women's History Month exhibition with this blog post about Salvation Army women in Egypt.

‘Evangelical Thrust’: The Salvation Army in the New Towns

In the 20th century the landscape of Britain's towns and cities began to change and the architecture of Salvation Army halls changed with them.

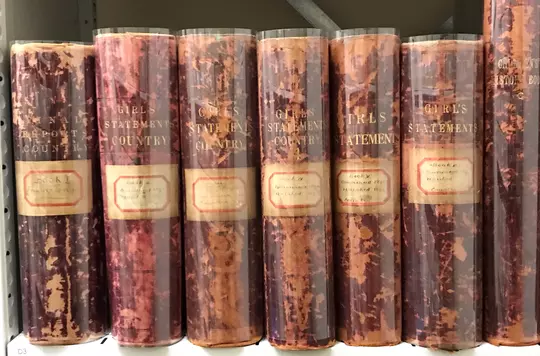

Death in the Archives

In our latest guest blog post, recent archives intern Lucy shares her research with The Salvation Army Women's Social Work Statement Books.

A garden lover's gem

This month’s blog ties in with #GreenWeek which takes place between 24 September and 2 October, raising awareness of issues associated with climate change and celebrating community action to protect the environment.