International Heritage Centre blog

“To live as we should do”: The Band of Love

“To live as we should do”: The Band of Love

This post by our Director, Steven Spencer, on The Salvation Army’s juvenile temperance society coincides with the publication of the ‘Temperance Past and Present’ special issue of The Social History of Alcohol and Drugs (Fall 2019), including Steven’s article on The Salvation Army.

One of the most active temperance organisations that campaigned for total abstinence from alcohol was the Band of Hope, a juvenile temperance society founded in 1847. It is also one of the temperance organisations most studied by modern historians. Annemarie McAllister has published several articles on the Band of Hope, writing that “With an estimated membership of half the school-age population by the early twentieth century, well over three million, the Band of Hope [… had a] wide range of activities and material to educate, entertain and empower millions of children, and […] mobilised its child members to lobby for legal change, including prohibition” [‘Giant Alcohol’, 2014, p103]

The Salvation Army has been committed to temperance as part of its evangelical Christian mission since it was founded in the 1860s and supported the work of the Band of Hope and other temperance societies. However, they also set up their own juvenile temperance society called the Band of Love which, while explicitly modelled on the Band of Hope, also had wider concerns than a straightforward promotion of temperance.

The earliest reference to the Band of Love dates from November 1892 when The Salvation Army’s weekly newspaper, The War Cry, reported that it was active in London and was likely to spread across the country. The Band of Love took the form of a weekly evening meeting which any child under 12 could attend, but they could also become a member by signing the Band of Love pledge and paying a subscription of a penny a month. The meetings were open to Salvationists and non-Salvationists alike and the object of the Band was “to check the tide of evil practises among the young” and “get their souls really saved- their hearts really changed.” By the end of 1893 Officers were being encouraged that “The Band of Love must be started at once in connection with every corps in Great Britain.” We know there were 50,000 pledged Band members across the UK by 1899.

The Band of Love was focussed on a temperance message of “getting our children to see the evils and curse of drink, and to secure their vow, before God, never to taste, touch nor handle it.” But it also had “extended moral and spiritual aims.” An early report of the Band asks: “Some might say, wherein does the Band of Love differ from the Band of Hope? As a rule the Band of Hope has but one step to its ladder, viz., Total Abstinence. The Band of Love has nine steps.” These steps are set out in the Band of Love pledge:

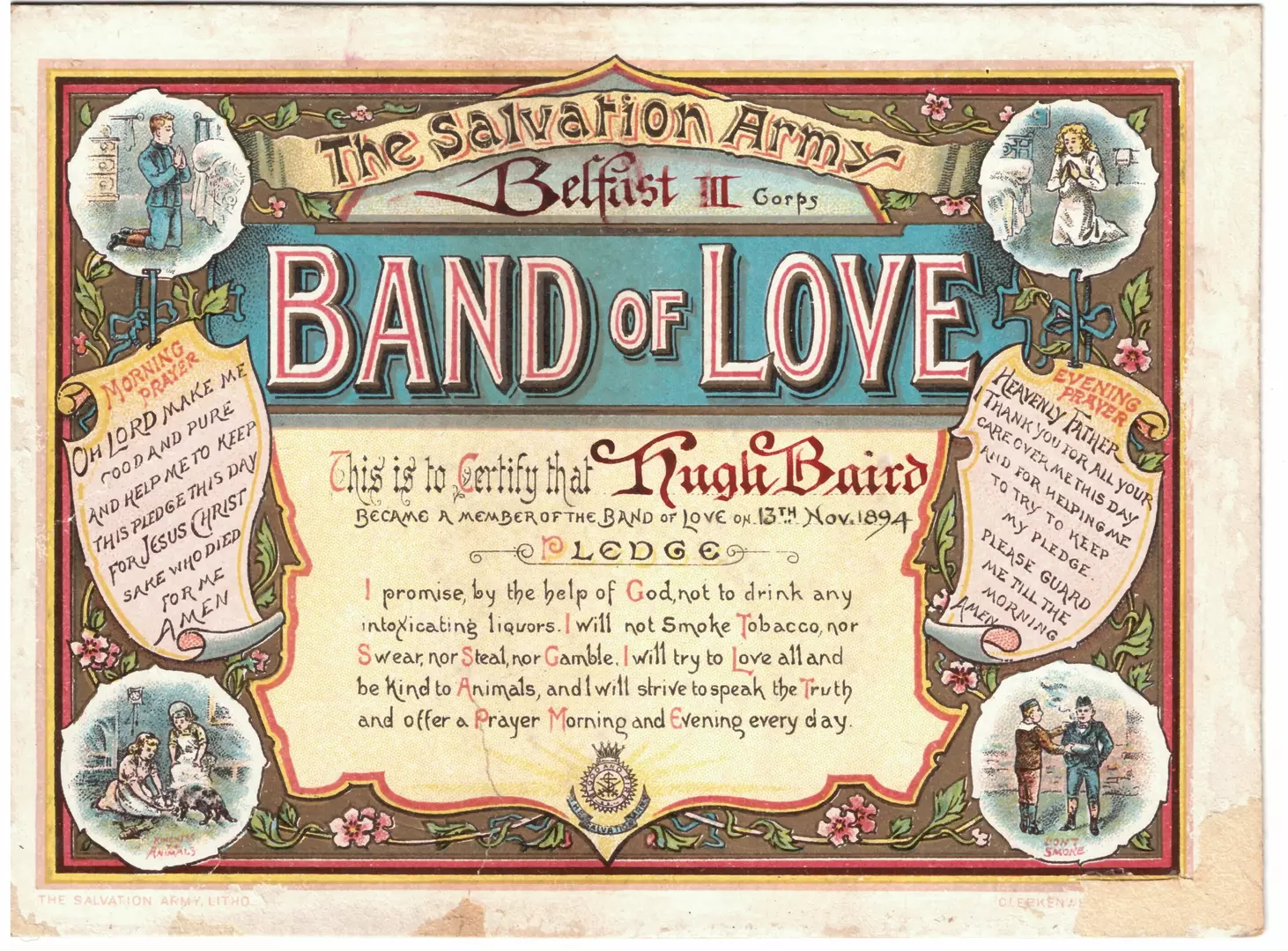

“I promise, by the help of God, not to drink any intoxicating liquors. I will not Smoke Tobacco, nor Swear, nor Steal, nor Gamble. I will try to love all and be kind to Animals, I will strive to speak the Truth and offer a Prayer Morning and Evening every day”

The pledge was summarised as “influencing the children to kindness to one another and to animals.” In fact, animal welfare often appears to sit alongside temperance as the main focus of the Band.

Unfortunately very few original records survive to document the work of the Band of Love and all we hold in our archives are a few of the Band’s brightly coloured pledge certificates and a single photograph, showing the Crouch End Band in around 1910. We know that the maintenance of a Band of Love members’ register was stipulated in regulations, but we are unaware of any of these that have survived.

However, we do hold a significant number of published sources that give detailed background to the setting up, development and activities of the Band of Love, including The Officer magazine for Salvation Army clergy and Orders & Regulations published for the leaders of what was called the ‘Junior Soldiers’ War.’ These give detailed advice on the content of Band of Love meetings. In 1893 The Officer magazine gave some examples of lessons being given at Band of Love meetings:

“Coal where and how it is obtained; the dangers, etc.

The Drunkard’s Progress, showing in pictures how step by step from a boy he grows to become a drunkard […]

The Effects Alcohol has on the body. This can be done by pictures, or better still, by chemicals […]

how the Band of Love pledge-cards are produced in eight colors by the art of lithographing.”

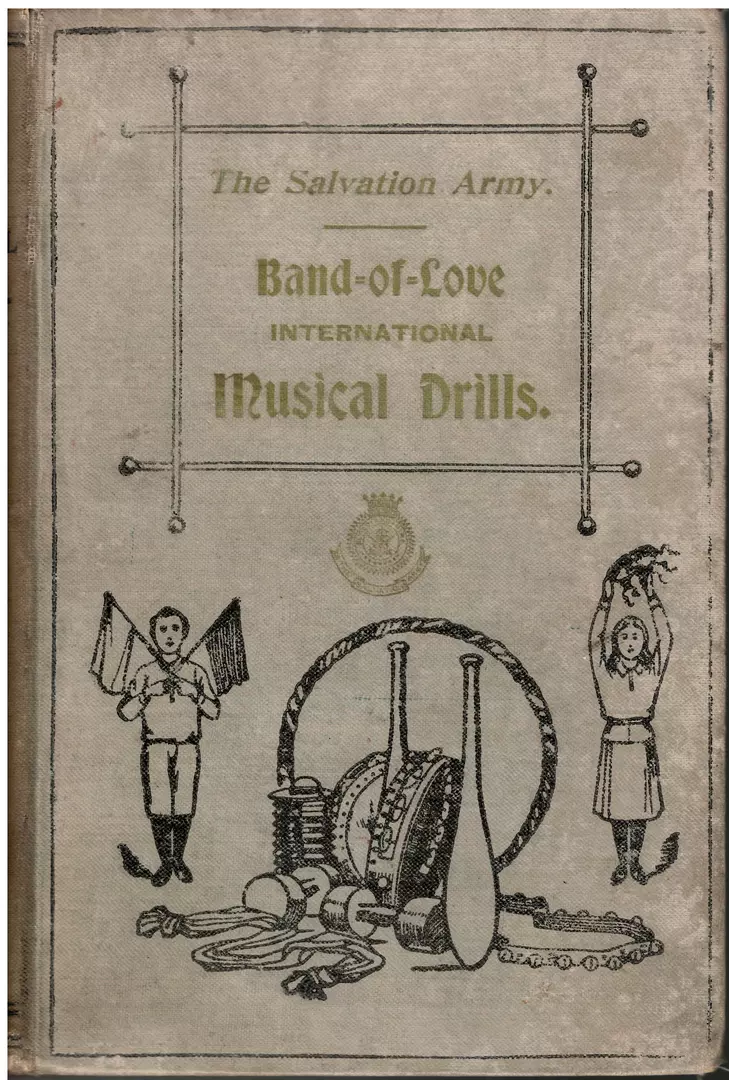

Suggestions were regularly included for various demonstrations, such as the ‘Chemical Talk’: using water, tincture of iron, bromide and tannin to dramatically illustrate “the blood of Jesus Christ cleansing from all sin.” In the early 1890s, when the use of magic lanterns was generally prohibited by The Salvation Army, special permission was given for their use by the Band, but “slides only may be used which are approved of by Headquarters” (magic lanterns were also widely used in the Band of Hope). In 1899 The Salvation Army published a volume of musical drills specifically for use by the Band. The meetings also included instruction in “various elementary subjects.”

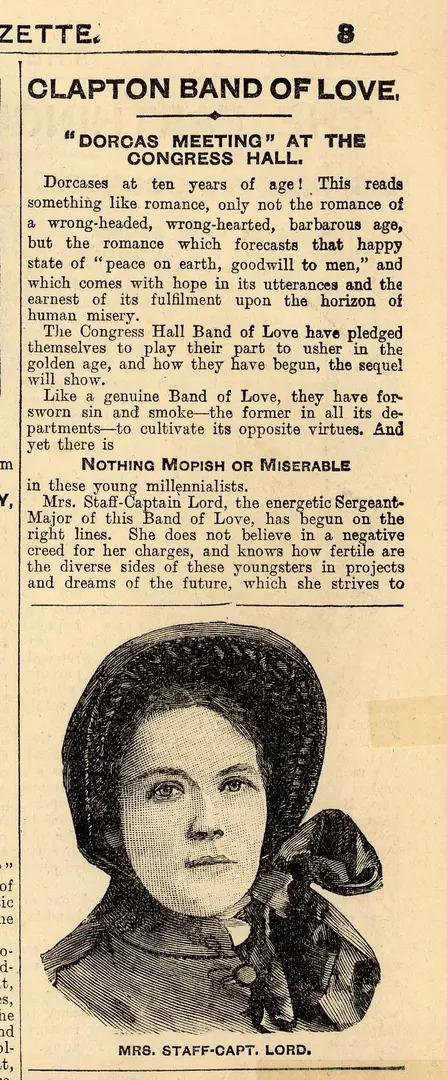

Other Salvation Army periodicals carried reports of the activities of individual Bands of Love and their members, particularly in The War Cry and The Young Soldier, a weekly newspaper for children. For example, in 1894 an account of a display of work by the sewing group (a ‘Dorcas meeting-’ named after Dorcas in the Acts of the Apostles) connected with the Band at Clapton Congress Hall reported that garments made by the group were for sale and 100 free tickets were given to “needy” children from the local areas who were entertained with “a liberal tea” and “package[s] of fruits and sweets.” As these periodicals are not at present indexed, there is plenty more to be learned about the range, membership and activities of various Bands of Love.

Steven

November 2019

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

‘Inside affairs’: cataloguing the Henry Edmonds papers

Henry Edmonds first encountered The Salvation Army’s predecessor, the Christian Mission, as a teenager in Portsmouth...

‘Eat like a Christian’: Vegetarianism in The Salvation Army’s Early History

It may seem surprising that vegetarian lifestyles began to gain popular recognition as early as the nineteenth century...

‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’: Salvation and Salvage at the Turn of the Century

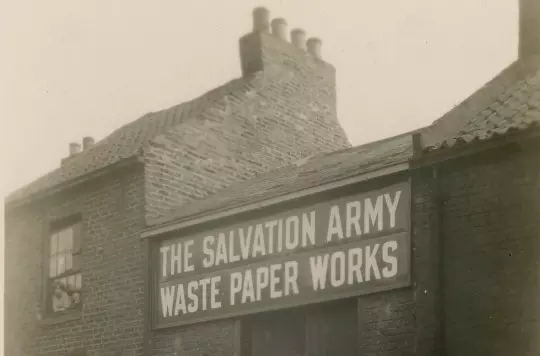

The paper recycling system was a metaphor for William Booth’s vision of the spiritual transformation of Britain’s poor...

'Rescue and Deliver Them': Attending the British Association of Victorian Studies Conference

Our archivist provides an account of The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre's panel at the British Association of Victorian Studies 2019 Conference...