International Heritage Centre blog

General Wickberg’s Second World War Papers

General Wickberg’s Second World War Papers

My first cataloguing project as Archives Assistant was a personal collection of General Erik Wickberg, who was in office from 1969-1974. Originally deposited at the Heritage Centre in the 1990s, these papers had been placed in storage when the Heritage Centre moved to a new location and were inaccessible for a number of years. They had therefore never been catalogued, their contents unknown. I have always been especially interested in individual stories, and how personal archives can change our perception of history. General Wickberg’s collection was a goldmine for this, as a large majority of the papers were related to his time working on behalf of International Headquarters in Sweden during the Second World War.

General Wickberg grew up in The Salvation Army, as both his parents were officers. After becoming an officer himself in 1925, Wickberg was promoted to the role of Liaison Officer in 1939. As Liaison Officer, it was Wickberg’s job to communicate between International Headquarters and Salvation Army officers in Germany, its allies and occupied countries. He would stay in this role throughout the war period, due to his ‘peculiar experience… with all matters concerning these countries [Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary].’ His six ring binder folders from this time, stuffed with documents, were my favourite part of the collection to catalogue. Issues primarily related to financial aid, but the correspondence detailing each individual case was an incredible view into daily life in the Second World War.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, International Headquarters was focused on the safety of officers in the occupied parts of Europe. Already, communication was cut off and trying to contact comrades on the ground in Germany and occupied territories was proving challenging. Wickberg was sent by Commissioner Karl Larsson to visit Berlin and Prague in late 1940 to provide an update on how warfare had affected The Salvation Army’s presence on the ground. As he wrote in his journey report for the US edition of the Scandinavian War Cry, Stridsropet; ‘it might be presumed that the work of The Salvation Army would be thoroughly disorganised by these new conditions. Such is not the case.’ Meetings were taking place as usual, with the only disturbance coming from sirens in the middle of the night. Social work facilities like the Women’s Rescue Home in Prague, were enlarged for extra support.

Unfortunately, as the war continued and German forces spread further north and east, The Salvation Army faced much tougher sanctions. The Nazis became much more suspicious of any organisation that could potentially provide aid to groups they sought to oppress. Norway was a particularly interesting case. The country was invaded in April 1940, and by November, officers were ‘strictly forbidden to communicate.’ In a letter from Larsson to General George Carpenter, he writes ‘if we should ignore these rules, the consequences would be most severe… our work in the country would probably be forbidden… even individual officers would have to go to prison.’ Larsson goes on to ‘illustrate what may happen because of a blunder’ by describing what happened with the Norwegian War Cry. An image of the Norwegian King was published on his birthday, leading to the editor being arrested and the War Cry itself being prohibited. Finally, Larsson emphasises the need for confidential correspondence between London and Stockholm to remain so, and ‘not be mentioned in the British (or any other) War Cry.’

In 1941, Larsson made the momentous decision to ‘break off every connection we have with London… for the sake of the Army,’ after having felt ‘more and more watched.’ He did this without obtaining the consent of General Carpenter, who was simultaneously dealing with the bombing of International Headquarters in London. In theory, this was to allow Wickberg and his colleagues to maintain contact with officers in Europe, but it was still not easy. ‘In Holland it looks as if our work has been lost. The information we possess is scarce and conflicting’, stated by Larsson in the Minutes of Council at International Headquarters in the same year. Officer ranks and titles were abolished in Germany for being too like those held by the Nazi military. In 1943, Adjutant Maria Lichtenberger had her permit for crossing between Belgrade and Zemun removed. Various Salvation Army shelters, homes, and hospitals across Europe were bombed, resulting in numerous casualties and property damage. Sadly, Captain Ilse Handel was killed when a bomb hit the maternity home in Berlin.

General Wickberg’s preservation of these important wartime documents provides us with the opportunity to get a different perspective on civilian life in occupied Europe during the Second World War. This is some of what we have learned from the English records – there are many in Swedish, German and French that could reveal much more!

Rose

September 2024

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

'The only religious body which has always some of its members in gaol'

Find out about the history of The Salvation Army's prison service, which goes back to 1883...

Marie Booth: the forgotten Booth daughter

Birkbeck intern Laura did some digging in the archives to find out more about William and Catherine’s sixth child.

Love Across the Sea

Take a look at some of the letters Brigadier Frederick Cox wrote to his wife while he travelled the world with William Booth.

Women’s History Month 2023: Salvation Army Women in Egypt.

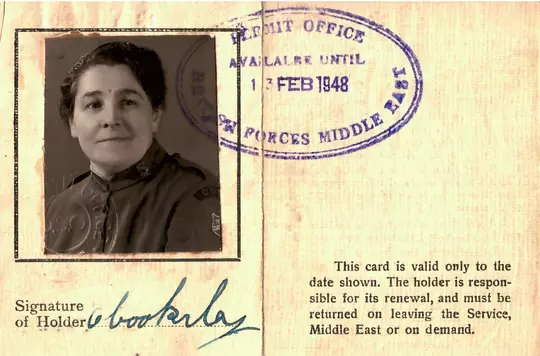

Catch-up on this years' Women's History Month exhibition with this blog post about Salvation Army women in Egypt.