International Heritage Centre blog

In Greenest India

In Greenest India

As we anticipate COP26, the UN Climate Change Conference being held in Glasgow from 31 October-12 November 2021, we take a look back at a tree-planting initiative undertaken by The Salvation Army in India in the early twentieth century. With thanks to Dr Catriona Ellis for suggesting the topic for this blog.

As one of our earliest blogs recounts, India became The Salvation Army’s first missionary field when a small group of officers ‘opened fire’ there in 1882. The Salvation Army’s work in India developed along unique lines with its own distinctive characteristics and features that were introduced in response to the local context. Foremost amongst these was the uniform, which was transformed to suit the climate in the subcontinent and conform to local expectations of religious preachers. This was closely followed by the practice of assigning Indian names to missionary officers from Europe, North America and Australasia. As time went on, The Salvation Army’s work in India extended into social work, as it did elsewhere, but India was the only country to have its own particular variant of General William Booth’s Darkest England Scheme – the ‘Darkest India’ Scheme, launched in 1896. Many of the forms of social institutions that were established in India were firsts for The Salvation Army and, in some cases, remained unique to India: general hospitals, day and boarding schools, village banks, a silk farm, a hand-loom factory, weaving industries, and settlements for so-called ‘criminal tribes’ (see our Subject Guide 1 for more information on these settlements).

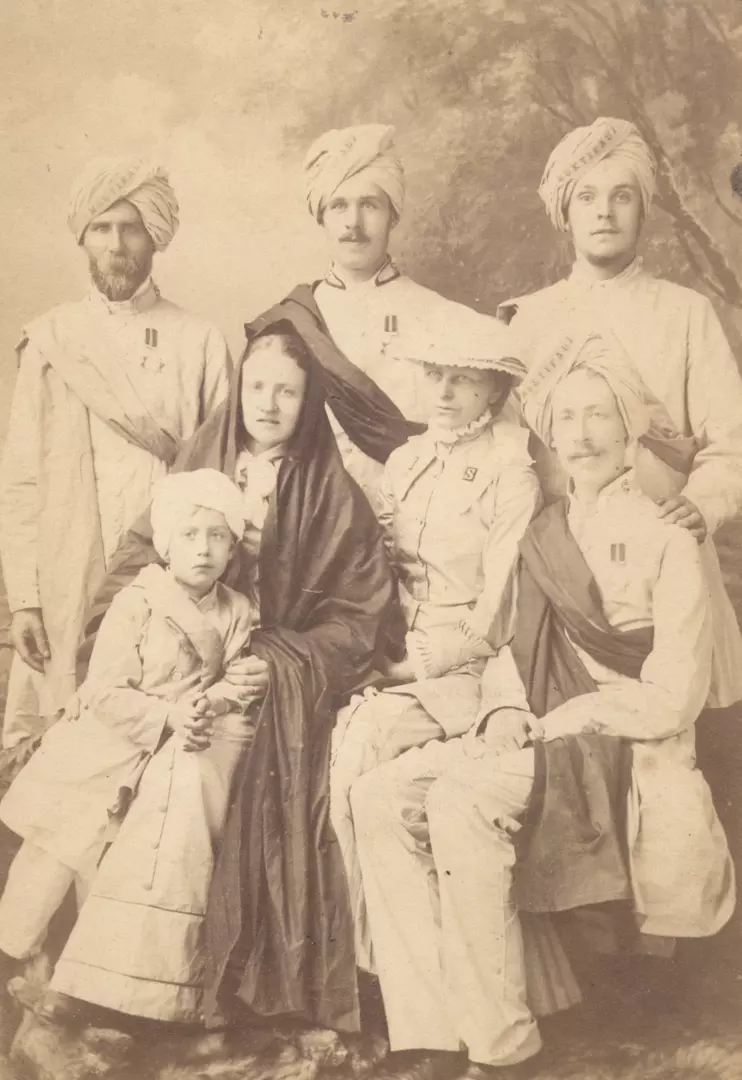

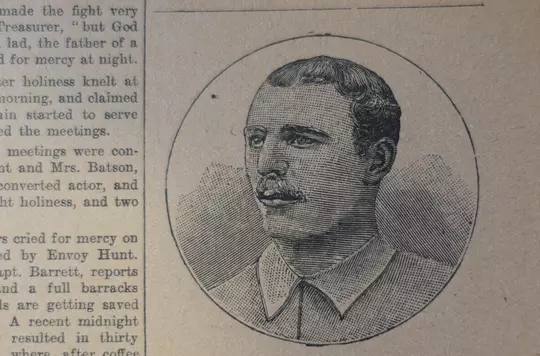

The leader of the Indian ‘pioneers’ was Frederick Tucker (pictured above, front right), a former member of the Indian Civil Service who joined The Salvation Army while in England on leave in 1881. Tucker would go on to be one of the most senior and trusted officers of The Salvation Army for nearly five decades until his death in 1929, marrying William Booth’s second daughter Emma in 1888 and taking the surname Booth-Tucker to cement his membership of the Booth family. He remained connected with India for much of his career, serving as leader of The Salvation Army in India until 1891 and then as Special Commissioner for India and Ceylon from 1907 until 1919. This was quite a privilege, even among senior officers, who are usually required to change appointment much more regularly.

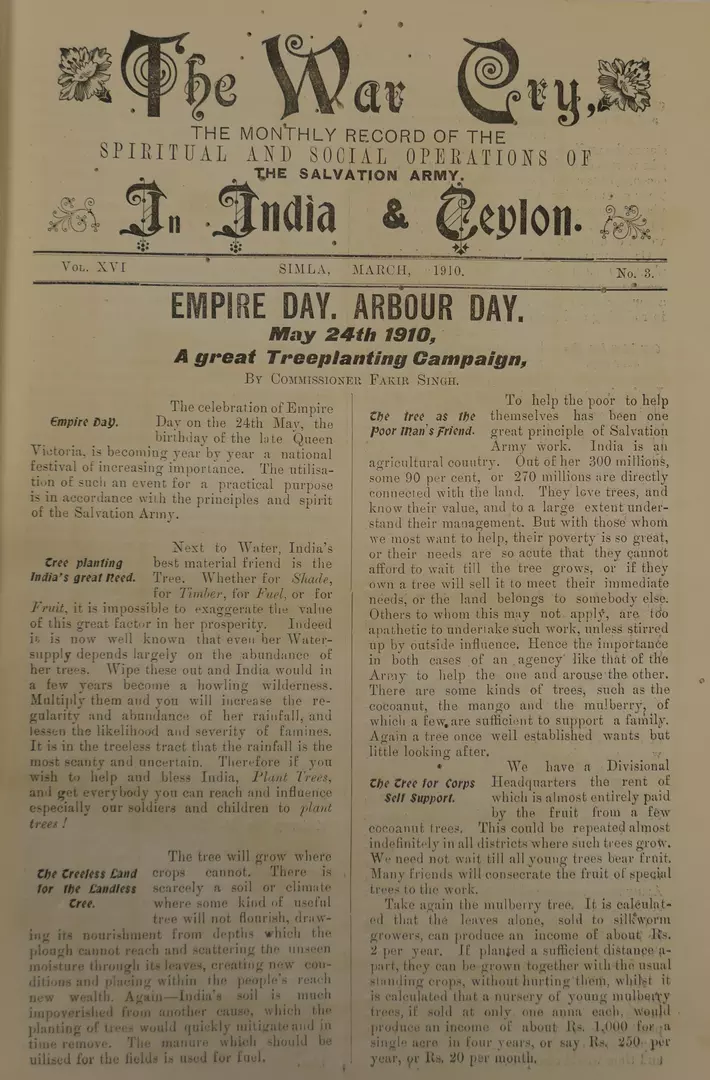

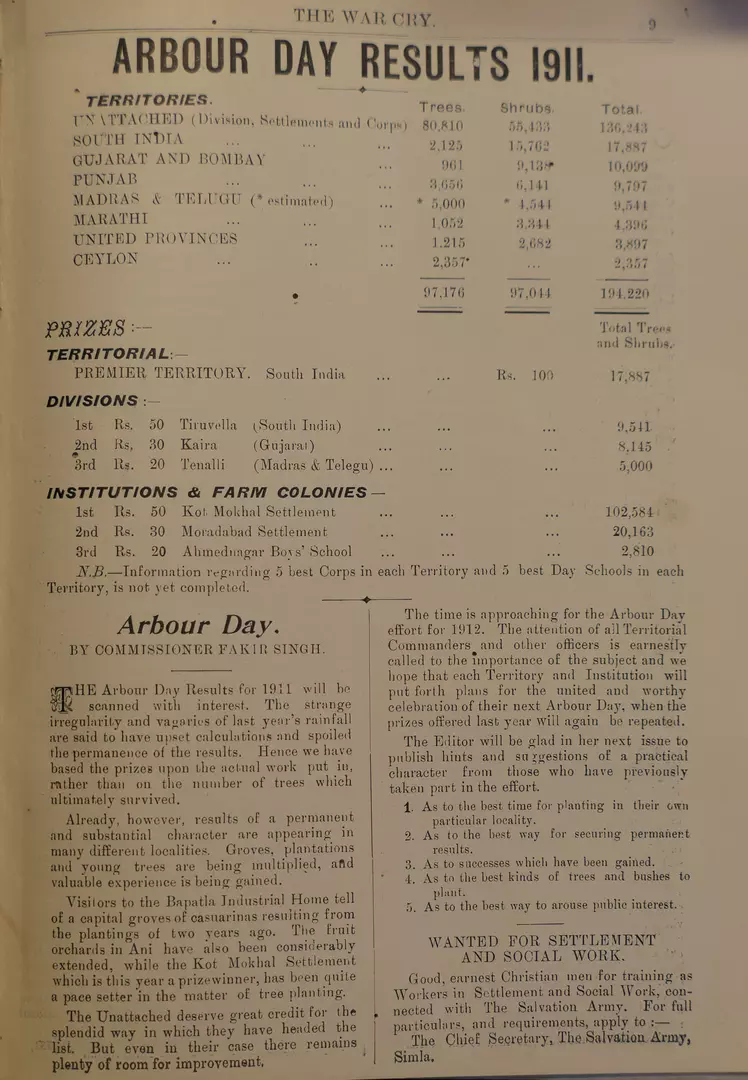

It was during his spell as Special Commissioner that Frederick Booth-Tucker (or Fakir Singh, as he styled himself) launched Arbour Day, a campaign to get Salvation Army corps and institutions across India and Ceylon planting and caring for thousands of new trees. Its announcement occupied the full front page of the March 1910 edition of The War Cry: the monthly record of the spiritual and social operations of The Salvation Army in India and Ceylon.

The initiative was proposed as a practical way of celebrating Empire Day, 24 May, the birthday of the late Queen Victoria. Tree-planting, it was argued, would bring prosperity to individuals, to corps (Salvation Army churches), and to all of India (and thereby, inferably, to the British Empire), by shaping the environment in beneficial ways and providing a long-term source of income, provided the trees were managed and exploited wisely. In recent decades, environmental historians have documented how scientific observation and experimentation in nineteenth-century India formed the basis of concepts in conservation and environmentalism that continue to influence thinking today, and this can be seen reflected in Booth-Tucker’s claim that India’s ‘water-supply depends largely on the abundance of her trees. Wipe these out and India would in a few years become a howling wilderness. Multiply them and you will increase the regularity and abundance of her rainfall, and lessen the likelihood and severity of famines.’ He is ambivalent about popular agrarian knowledge and practice, apportioning it both criticism and praise, but either way his position is articulated so as to support his tree-planting project. On the one hand, he argues that ‘India’s soil is much impoverished from another cause, which the planting of trees would quickly mitigate and in time remove. The manure which should be utilised for the fields is used for fuel.’ On the other, he contends that the 90% of people in India whose lives and livelihoods were at that time directly connected with the land ‘love trees, and know their value, and to a large extent understand their management.’

Arbour Day was given extensive promotion in The War Cry in the months leading up to Empire Day with promises of significant cash prizes for those who ‘distinguished themselves’ and free silkworm seeds offered to those who provided evidence of having planted mulberries or castors with a view to starting a sericulture industry. To ensure that trees and shrubs continued to be cared for after planting, only half the prize would be awarded immediately with the balance paid ‘as soon as possible after 1 December, on condition that not less than 50 per cent of the number planted are doing well, those that may have failed being replaced.’ Participants were encouraged to plant mulberry, mango, coconut, shisham (rosewood), castor, cassava, and babul which had been chosen for ‘their utility’ and ‘their wide diffusion’. Copious advice was printed on where and how to plant the trees, and the support of government agricultural experts was enlisted. Ultimately, however, the campaign was hampered by unfortunate timing as the chosen day closely followed the death of King Edward VII on 6 May and coincided with the late arrival of the monsoon in some areas.

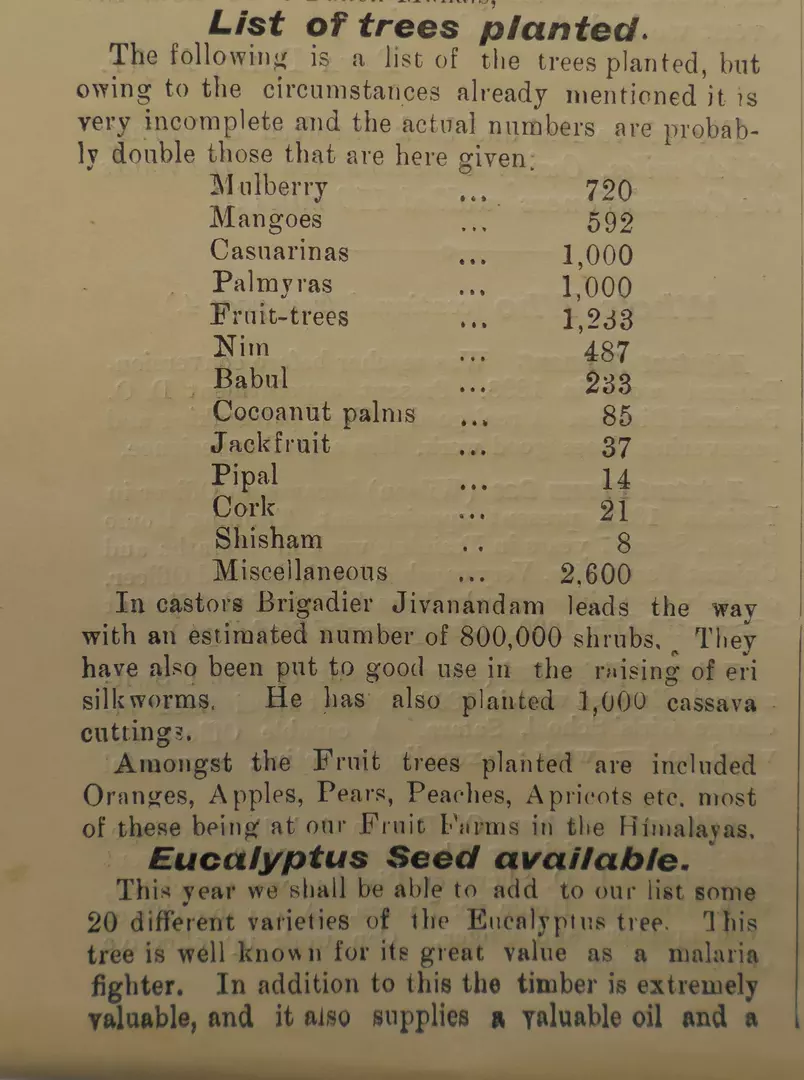

Despite these difficulties, the following May The War Cry reported that ‘a splendid beginning had been made’ and gave a supposedly conservative list of some 8,000 trees and 800,000 shrubs that had been planted as part of the first Arbour Day campaign. A much greater variety of trees had been planted than those on the official list, including casuarinas, palmyras, nim (neem), jackfruit, cork, pipal and other fruit trees. The lessons of the previous year were learned, and a more flexible approach was chosen for the 1911 Arbour Day campaign: each Salvation Army Territory within India was permitted to select a suitable date to hold its Arbour Day celebrations between Coronation Day on 22 June and the Delhi Durbar on 12 December. Another new feature was the introduction of 20 varieties of eucalyptus to the approved list of trees. The main reason given for this addition was that eucalyptus was ‘well known for its great value as a malaria fighter’, but the financial value of its timber, oil and gum (kino) were also noted. The fact that it was fast growing and had varieties suitable to a range of climates further enhanced its appeal. In all subsequent years that Arbour Day was celebrated, eucalyptus continued to be one of the main trees promoted for planting, principally for its health benefits, alongside mulberry for silkworms, ‘cassava as a famine food, thornless cactus and variegated alfalfa for fodder, and the best kinds of fruit trees’.

From its first year, Arbour Day was promoted as an initiative to involve children in. The idea was for pupils at The Salvation Army’s day and boarding schools to do the lion’s share of the planting and each school was encouraged to appoint a ‘jemadar’ or ‘Arbour Day Corporal’ responsible for ensuring the care of the young plants. In 1913, the date selected for Arbour Day was the Viceroy’s birthday, 20 June, which had been designated a national Children’s Day to celebrate the recovery of Viceroy and Lady Hardinge from the assassination attempt made on them the previous year. However, the breakdown of the 1911 Arbour Day results shows that over 60% of the total were planted by two of The Salvation Army’s ‘settlements’: Kot Mokhal, which planted a staggering 102,584 trees and shrubs, and Moradabad, which planted 20,163. The Salvation Army received government subsidies to run these settlements under the Criminal Tribes Act, which designated certain Adivasi, or indigenous ethnic groups, in India ‘habitually criminal’. Recent scholarship has shown that colonial land management policy in India was closely linked to policies which sought to impose sedentary settlement on itinerant groups. The criminalisation of nomadic people who traditionally lived in forested areas made way for both the commercialisation of forests and the incorporation of the people into the systems of agricultural and industrial production. It is noteworthy and little-known that for a decade this tree-planting initiative was a significant feature of The Salvation Army’s sedentary settlement work, and it is something that may merit academic attention.

As the years passed, the advice published in The War Cry built on the experience of previous years, but difficulties relating to rain and droughts were repeatedly reported. After 1913, Arbour Day attracted less and less coverage in The War Cry and May 1918 finds the last mention of it that I’ve managed to trace. Most of the promotion of Arbour Day was penned by Frederick Booth-Tucker himself, and he even created an ‘Arbour Day Catechism’ to guide the celebration of the event. In 1919, however, Frederick Booth-Tucker received a new appointment as Travelling Commissioner, which saw him leave India and seems to have spelled the end for The Salvation Army’s Arbour Days in India too. However, in July 1947 civil servant and botanist M.S. Randhawa organised a week-long national tree-planting festival, which has since become an annual event called Van Mahotsav.

Ruth

October 2021

All the World’s a Fair: The World-Wide Salvation Army Exhibition, 1896

125 years later, we revisit the 1896 exhibition in the context of the nineteenth-century history of World Fairs.

Dedicated Followers: Uniforms and The Salvation Army’s Attitudes to Fashion

Everybody recognises a Salvation Army uniform. But what was behind their introduction in the late nineteenth century?

Davie Haddow, the converted international footballer

As the 2020 European Championship nears the finals, our Director, Steven Spencer, reflects on the life of Davie Haddow, The Salvation Army's 'Converted Footballer'.

The accession in the suitcase

For archivists, the arrival of an unexpected parcel tends to raise mixed emotions...