International Heritage Centre blog

'Rescue and Deliver Them': Attending the British Association of Victorian Studies Conference

'Rescue and Deliver Them': Attending the British Association of Victorian Studies Conference

This year’s British Association of Victorian Studies conference was hosted by the Scottish Centre for Victorian and Neo-Victorian Studies at the University of Dundee from 27-30 August and we were delighted to have our proposal for a panel session accepted for the conference. The conference theme, Victorian Renewals, tied in very well with a number of current research and outreach projects that make use of our collections, so this was an excellent opportunity to share these projects with an audience of researchers specialising in the history, literature, art and culture of the nineteenth century. It was also a chance for us to learn more about the latest research in Victorian studies, improve our understanding of the historical context of our collections, and meet people who might have an interest in using our archives for their own research.

The title of our panel was ‘“Rescue and deliver them”: the archives of The Salvation Army’s Victorian social work’. It featured three papers and was ably chaired by Professor Kirstie Blair. Kirstie currently leads the fascinating Piston, Pen and Press project, which is researching literary culture amongst industrial workers between 1840 and 1918.

The first speaker on our panel was Professor Julie-Marie Strange who co-authored the recent book The Charity Market and Humanitarianism in Britain, 1870-1912 which drew on her research in our archives. Julie-Marie’s paper, ‘Love, Money and Jesus: Fundraising for a Better World with the Salvation Army’, built on the foundations she had laid down in this book to suggest a new way of thinking about the relationship between religion, class and capitalism in the late-Victorian period. Arguing that The Salvation Army’s importance at that time has often been overlooked in scholarly research, she proposed that it merits renewed academic attention because it was at once ‘a massive organisation, oriented self-consciously towards the working classes’ and ‘a visionary organisation that harnessed technological and consumer novelties to become a remarkable fundraising machine’.

Julie-Marie went on to show that The Salvation Army’s embrace of innovative marketing techniques was not restricted to fundraising; they suffused its social and evangelical work too. The success of these techniques in engaging with their desired audience was illustrated with examples from oral histories and diaries of working class people including, touchingly, a lonely sixteen-year-old dressmaker who described feeling uplifted by The Army’s open air services. Surviving donation slips from the Grace-Before-Meat fundraising scheme had also been studied, revealing that the most committed contributors were working class people, themselves living precarious lives, who valued the work of The Army and wished to support it in helping others like them. Long neglected by classical labour history because its members and supporters did not fit the mould of an ‘idealised’ socialist and secular working class, Julie-Marie’s paper made a convincing case for writing The Salvation Army into working-class history as a means of understanding the late-Victorian working class in all its heterogeneity.

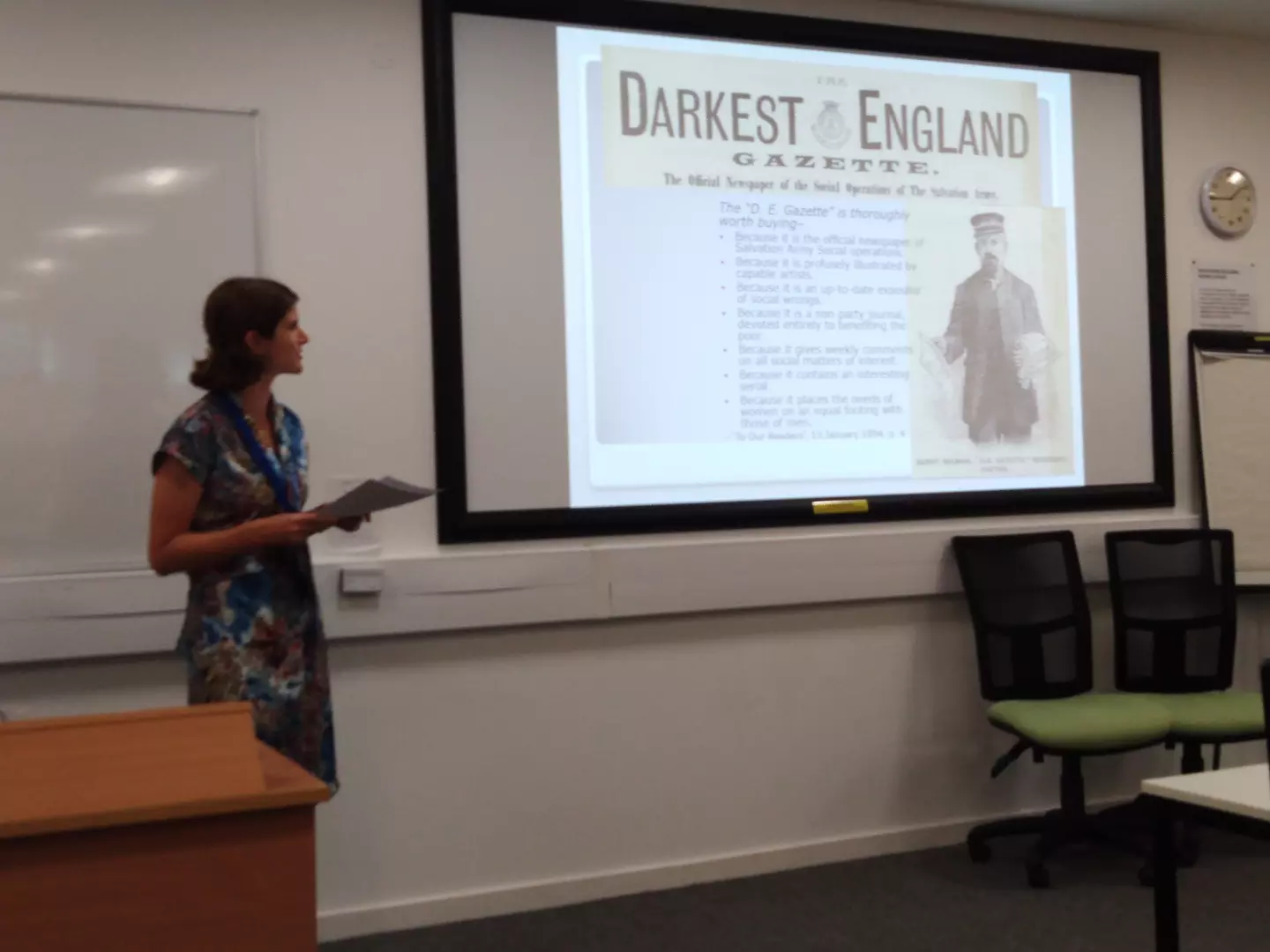

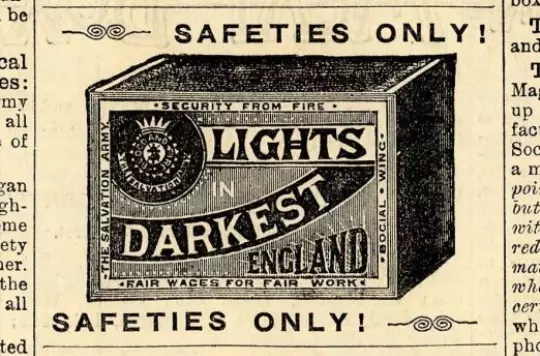

The second paper was given by Dr Flore Janssen, the Digital Humanities Project Officer here at the Heritage Centre. Flore’s paper, ‘New Approaches to the Salvation Army Social Work: the Digital Darkest England Gazette, 1893-94’, introduced our pilot digitisation project and gave the audience a flavour of what they can expect from the open access resource Flore has been building over the course of this year. The Darkest England Gazette was one of the shortest-lived of The Salvation Army’s many newspapers and magazines. It was a twelve-page, illustrated penny magazine published weekly from July 1893 until June 1894. Despite its extremely short run, it provides fascinating insights into the wide range of social problems The Salvation Army was preoccupied with in the late-nineteenth century. Some of these are well-known but others are more surprising. In our July blog, Flore gave an overview of one of The Salvation Army’s better-known campaigns of the 1890s—its Lights in Darkest England safety matches—but her paper also described a number of other more unexpected concerns addressed in the pages of the Darkest England Gazette such as vivisection, gambling and substance abuse.

Flore argued that the Darkest England Gazette stands out as a particularly approachable and useful source for researchers because it was outward-facing by design. Unlike some of The Salvation Army’s internal publications, the Gazette explains and justifies the aims and practices of William Booth’s Darkest England scheme for an outside audience. The newspaper also includes a great variety of types of content combining documentary illustrations, photographs and reportage with more artistic content like poems, songs and serials influenced by contemporary popular slum fiction. Her paper described how the online portal is being devised with the express aim of helping researchers to navigate this diverse content. One navigation aid which has already been released is a series of themed research guides.

My own paper, ‘Rescuing the “Fallen” Woman by Revisiting the Archives’, was the last on the panel. I argued that the surviving case records from The Salvation Army’s rescue homes for women have not been used to their full potential, suggesting that, in part, this may be due to the misconception that the Victorian term ‘fallen’ meant something much more limited than it actually seems to have done. I used examples from Salvation Army magazines and annual reports as well as from the case records themselves to demonstrate that the so-called ‘fallen’ women assisted in Salvation Army rescue homes were not only, nor even predominantly, women working in prostitution as has often been assumed. Rather, the homes accommodated women and girls whose behaviour transgressed Victorian norms of respectability in a wide range of ways, not limited to sexual impropriety. This included women referred from Police Courts or discharged from prison, alcoholics, women who had left their homes because of abuse, women who were destitute, and even teenage girls who had done nothing more than stay out late with friends.

I gave an overview of the case records we hold which are contained in volumes called statement books. In the late-nineteenth century, The Salvation Army opened around 20 rescue homes for women in many parts of the UK and Ireland. These homes were required to submit statements about recently discharged residents to the central rescue work headquarters in London on a monthly basis. At headquarters these statements were transcribed into two series of volumes: a London series, for all the homes in London, and a Country series, for all the homes in other parts of the country. We are fortunate to have both series virtually complete in the archives at the International Heritage Centre where they are accessible for research, so I encouraged any listeners who might have an interest in using them to get in touch.

When it came to the question and answer session, it was clear that the audience had been engaged and intrigued by the things we had spoken about and they raised many thought-provoking points. Discussion topics ranged from issues around accessing institutional archives to historiographical approaches, and from the history of animal welfare campaigning to the possibility of tracing the artists behind the Darkest England Gazette illustrations. I was very pleased to be pointed towards the archive of women’s petitions to the Foundling Hospital requesting admission for their children. These bear some similarities to the statement and interview books we hold at the Heritage Centre, and it was suggested that comparative study might reveal some overlap with women applying to both agencies.

The conference was a feat of organisation, with as many as 9 panels running simultaneously, and those of us who attended from the Heritage Centre thoroughly enjoyed all of the panels and plenaries we saw. One highlight of the trip was getting to see The Salvation Army’s Strathmore Lodge in real life. Now a lifehouse, The Salvation Army bought this former industrial school in 1900 to be its second Scottish rescue home for women.

Ruth

September 2019

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

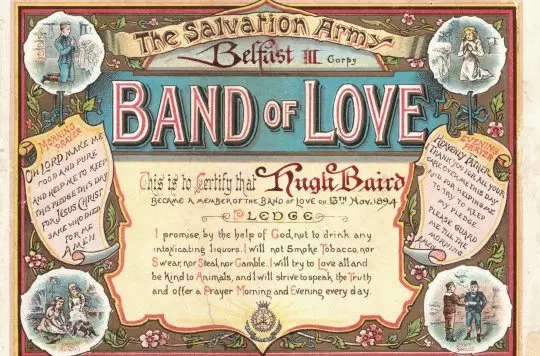

The Band of Love

The Salvation Army has been committed to temperance as part of its evangelical Christian mission since it was founded in the 1860s...

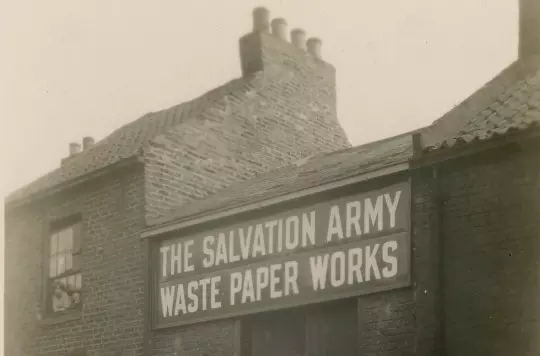

‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’: Salvation and Salvage at the Turn of the Century

The paper recycling system was a metaphor for William Booth’s vision of the spiritual transformation of Britain’s poor...

William Booth: The Man of Emotion

In our second guest blog, biographer Gordon Taylor shines a light on William Booth as a 'Man of Emotion'...

‘Matches and Morals’: The Salvation Army and Consumer Activism in the 1890s

The Darkest England Gazette gives an insight into The Salvation Army's promotion of its ethically-produced 'Darkest England Matches'...