International Heritage Centre blog

‘A constant and outspoken friend’: Frances Willard and Catherine Booth-Clibborn

‘A constant and outspoken friend’: Frances Willard and Catherine Booth-Clibborn

In the archive of the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre, we hold a series of six letters relating to Frances Willard, the president of World’s Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WWCTU) based in the USA. The letters date from 1893-1894 in a period when Willard was visiting the British section of WWCTU, the British Women’s Temperance Association. Willard had travelled to Britain at the end of 1892 and the following summer saw a schism within the British Women’s Temperance Association. Its president, Lady Henry Somerset, had led the Association to broaden its focus beyond temperance to include other issues, such as social purity, the opium question and, most prominently, women’s suffrage. This approach, known as ‘Do Everything,’ was based on Willard’s WWCTU and her presence exacerbated existing opposition to this approach within the BWTA. The Women’s Total Abstinence Union was set up by those members who thought it more important to maintain a focus solely on temperance.

The majority of our letters are written to Catherine and Arthur Booth-Clibborn and they tell of the strong connection between The Salvation Army and the largest temperance organisation in the world. Catherine Booth was the eldest daughter of William and Catherine Booth, the founders of The Salvation Army. Catherine had led the introduction of The Salvation Army into France in 1881 at the age of 22, where she earned the title ‘La Maréchale’- ‘The Marshal’. In 1882 she began work in Switzerland, where she had been first expelled and then imprisoned for preaching. In 1887 she married a fellow Salvation Army minister, Colonel Arthur Clibborn. Upon marriage, they combined their surnames as Booth-Clibborn.

In the first letter, dated 23 August 1893, Willard is asking a Mrs Walker in Switzerland to make an introduction to “Colonel and La Maréchale Booth-Clibborn” as “our hearts are in warm sympathy with the Salvation Army.” Willard adopts the military metaphor herself when signing off the letter with her hope that she and Mrs Walker will “meet in London or Paris, when we are all on the war-path”. The letters materially display the interconnections with the global temperance movement; this first letter is written on the letterhead of the British Women’s Temperance Association, with the very apt telegraphic address of ‘Abstinence, London’ for its offices on Farringdon Street.

A week later, Willard was in the south of France meeting Catherine Booth-Clibborn, an event recorded in her diary for the 31 August 1893 (which is made available online by the Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU archive):

'La Maréchale, her month old child, her nurse, secretary & friend all came down to Aigle in a landau that Isabel provided & we rode together to Lausanne where she left to preside over her salvation army officers. She has been expelled from three cantons by Swiss Protestants-they fear to be diminished in numbers by the Salvation Army; the Catholics leave them alone. […] It is wonderful to hear the account of La Maréchale in Geneva- meetings at 6am, rich people paying 20 francs to get a seat- public houses &c practically closed- imprisonments- trials- release- papers full of the turmoil & when in 3 months she left all breathed freer Sc said "now the theatres & publics will be patronized again!"'

Willard had returned to London by 5 September when her next letter was sent, on the headed paper of the Westminster office of the WWCTU in Albany Buildings. In this first letter to Catherine, “My dear Friend and Sister,” Willard affirms her “hope to see you not infrequently in future, for we feel strongly drawn to you by the tie of our mutual love for our Master and for the Humanity He came to save.” She also draws Catherine’s attention to a “statement about you in connection with the Army” appearing on the first page of “Lady Henry’s paper” for which Willard disclaims any involvement- “During the weeks we were in Switzerland, we had no cognizance of the paper whatever.” Willard and Lady Somerset dominated the transatlantic temperance movement in the 1890s, but the two had also developed a close friendship and Willard was staying with Lady Somerset her during her time in Britain. Willard formed several such close attachments throughout her life and this is reflected in her ‘strong feelings’ expressed for Catherine Booth-Clibborn.

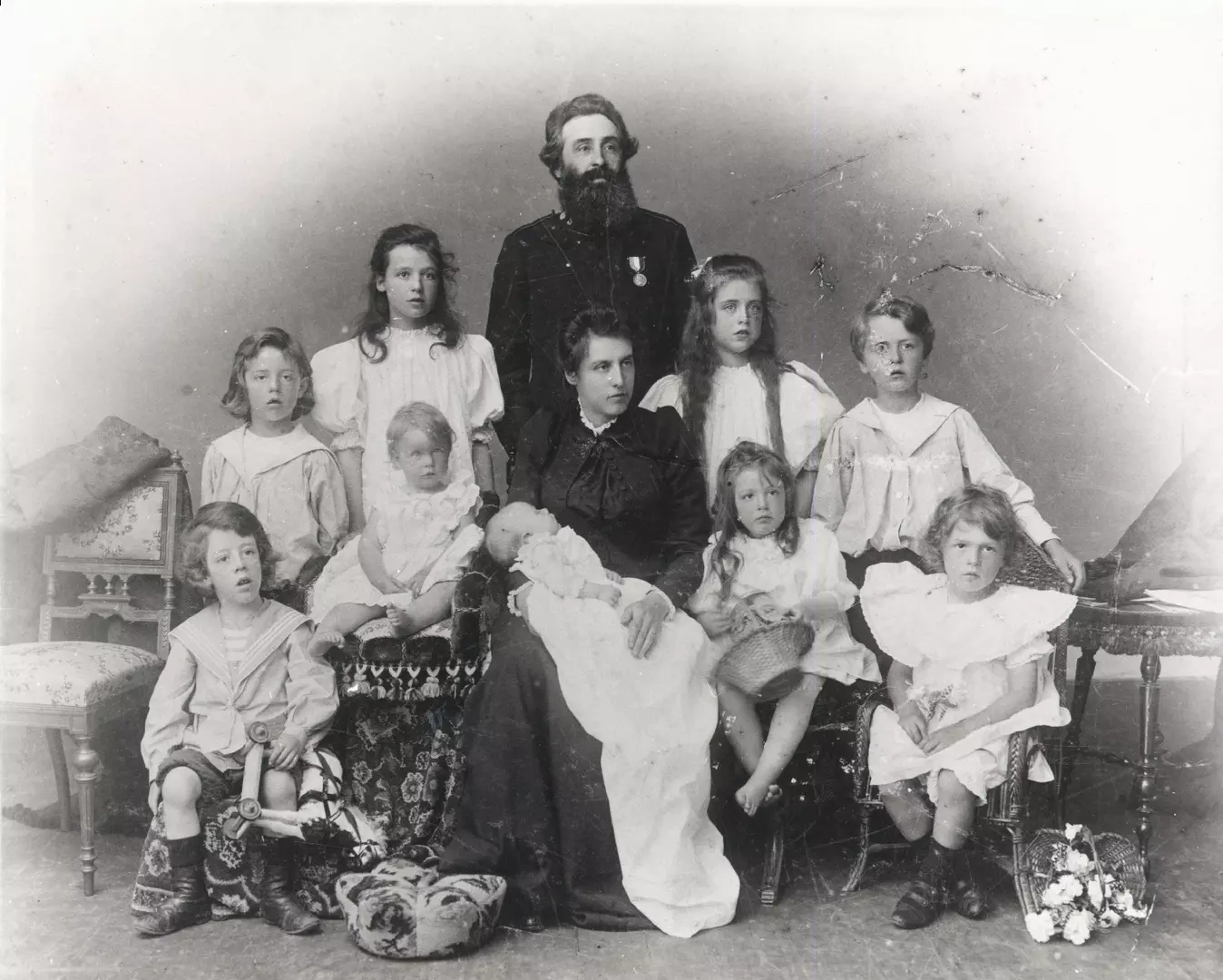

In a postscript, Willard recommends the “most artistic” portrait photographer Alice Hughes who could photograph “you and your husband and children in a group”. We don’t know if this ever happened, as the Booth-Clibborn family portrait reproduced here was taken after 1899 when their ninth child was born. Willard herself had been photographed by Hughes earlier in 1893, a print of which is now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

In a letter a week later to Arthur Booth-Clibborn, ‘Dear Brother,’ written from the Cottage attached to Lady Somerset’s Reigate Priory, Willard is proposing “a unique sketch and interview with La Maréchale” to appear in the periodical of the WCTU, the Union Signal. This periodical, which was published from 1874 to 2016 is described here by Willard as “the women’s paper of largest circulation.”

A follow-up letter to Arthur on 18 September indicates that the article on Catherine was ‘partly prepared’ but would be held off until “a time when it will be likely to do most good” as the Union Signal was then covering the WWCTU convention. She also acknowledges ‘photographs and so forth’ that Arthur has sent for the article. The ‘sketch’ of Catherine Booth-Clibborn appeared in two parts in the Union Signal for 21 and 28 December 1893, sadly without any photographs. Willard’s article spends some time on the Booth-Clibborns’ physical appearances before moving on to Catherine’s development as a preacher:

'“La Maréchale […] may be thirty-five years old, but although the mother of five lovely children, she seems but twenty-five or thereabouts. […] Her parents had marked physical advantages, which she inherits in accentuated form. She is tall, like her father, and of erect and graceful bearing. She has a countenance full of strength, sweetness, and light, fair brown hair, soft and abundant, with a chestnut tinge, plaited behind and without crimps or puffs, lying in waves around her delicate face with its sweet tender mouth, frank gray-blue eyes, pencilled eyebrows, regal Roman nose, brilliant complexion, thoughtful forehead, and smile as sweet as summer. […] Arthur Booth-Clibborn […] is for a man as handsome and every way attractive as she is for a woman.

Miss Booth commenced public work when only fourteen years of age, driven to it by an irresistible urging of divine love after she had received a remarkable baptism of the spirit. It was at that time a thing almost unknown for a young woman (and how much more a child) to stand up to speak in public in England. The prejudice against any woman speaking before a mixed audience was very great, as her devoted mother had proved.'

The articles are then taken up with an account of Booth-Clibborn’s evangelical campaign in France and Switzerland, especially the opposition faced:

'The indignities and brutality endured by the officers of the army in Switzerland are beyond description. Every kind of instrument has been violently used against them, sticks and stones, knives, whips, flails, pitchforks, guns, revolvers and what not. In one year no less than two hundred brutal assaults occurred. The commissioners themselves have been frequently struck and stoned. They were imprisoned several times for holding meetings or re-entering cantons from which they had been thrust out.'

The final two letters in the archive are written to Catherine Booth-Clibborn from the Cottage at Reigate, sending her the articles from the Union Signal and adding her to the subscription list for ‘Lady Henry’s paper including an “item” based on Booth-Clibborn’s letters. Willard reports that “her paper has ‘caught on’ as they say here.” This is presumably the Woman’s Herald, although the history of the periodicals of the BWTA is rather convoluted in the early 1890s and the paper in question may be a different title. The absence of a digitised version of the Woman’s Herald means that we have been unable to locate this article on Catherine Booth-Clibborn. The Union Signal, however, is available online and the two part ‘sketch’ by Willard of La Maréchale is available via Archive.org.

When Frances Willard died in February 1898, Catherine Booth-Clibborn’s sister-in-law, Florence Booth wrote her obituary in The War Cry, calling her “a constant and outspoken friend [of The Salvation Army], both on the platform and in the Press.”

Steven

October 2024

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

General Wickberg’s Second World War Papers

The papers of General Wickberg are a goldmine of personal stories about the impact of war...

'The only religious body which has always some of its members in gaol'

Find out about the history of The Salvation Army's prison service, which goes back to 1883...

Marie Booth: the forgotten Booth daughter

Birkbeck intern Laura did some digging in the archives to find out more about William and Catherine’s sixth child.

Love Across the Sea

Take a look at some of the letters Brigadier Frederick Cox wrote to his wife while he travelled the world with William Booth.